El País Lies When Claiming That Climate Change “Threatens the Future of Food,” It Doesn’t

By Linnea Lueken

El País posted an article “The era of scarcity: Climate change threatens the future of food,” claiming that climate change is making food shortages worse, highlighting Japanese rice production and Brazilian coffee, among other crops, as examples. This is false. While production of certain crops may suffer some seasons, data show that crop production and yields have increased substantially amid the past century’s modest warming.

El País’ post covers so many topics it feels like a climate-alarmist Gish-gallop, with too many topics so shallowly covered. It gives the feeling of overwhelming evidence, even if each example individually fails to support the claims made. Rather than debunk every claim, many of which have already been discussed across hundreds of previous Climate Realism articles on crop production, this article will just refute a few specific examples cited in El País’ woefully misleading article.

The article begins by pointing towards Japanese rice production. Although El País admits that many other factors have contributed to this year’s rice shortage, they assert that the main cause is allegedly climate change-induced heat and heavy rainfall, “fear of natural disasters, and the pressure of mass tourism.” Mind you, climate change cannot cause “fear of natural disasters” or “the pressure of mass tourism,” and neither of those have anything to do with rice production. These claims are just a distraction.

In 2024, rice was stockpiled in anticipation of a serious earthquake, which added to higher prices and less availability on the market. On top of that, there has been a large increase in visitors to Japan “eager to eat sushi,” which also strains rice supplies in the relatively small island nation. Neither of these are climate change related, and the actual largest reason production is declining in Japan is also not climate related.

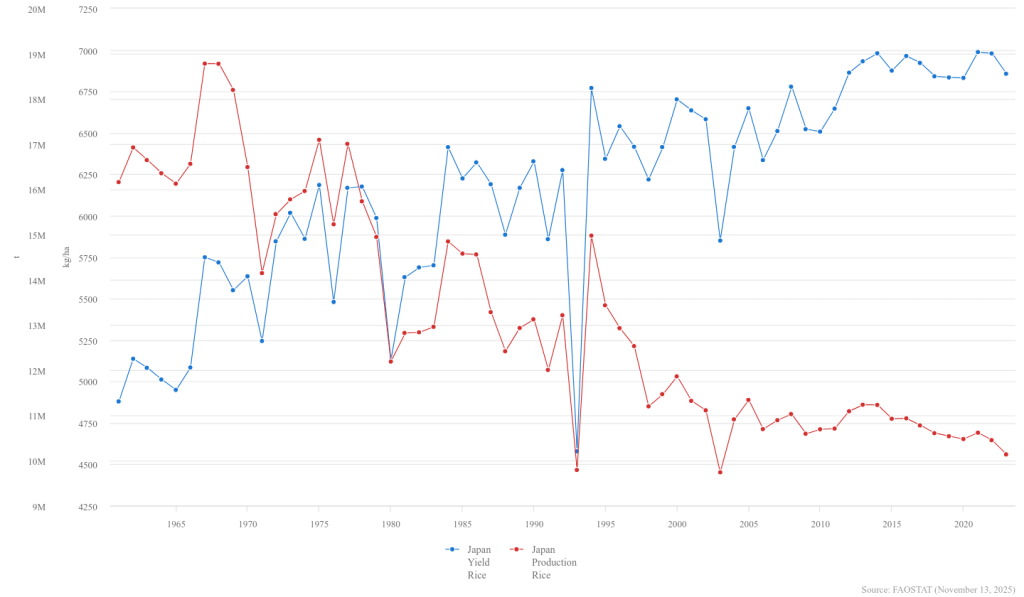

Japanese rice production has declined since recordkeeping began in 1961, but data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) also show that yields per acre have increased substantially over the same period (See figure below). This indicates that it is not an environmental or climate issue primarily driving the decline. In fact, what El País neglected to mention, is that for decades the Japanese government has actively discouraged rice production in order to protect rice prices.

An article at nippon.com, written by Yamashita Kazuhito, explains that the influx of visitors, environmental pressures, and stockpiling only account for a small percentage of the issue. The main driver of rice shortages is government policy. In order to protect the price of rice from dipping, the Japan Agricultural Cooperatives and Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (MAFF) order less acreage be used for growing rice, “based on the premise that demand for rice is decreasing by 100,000 tons every year.”

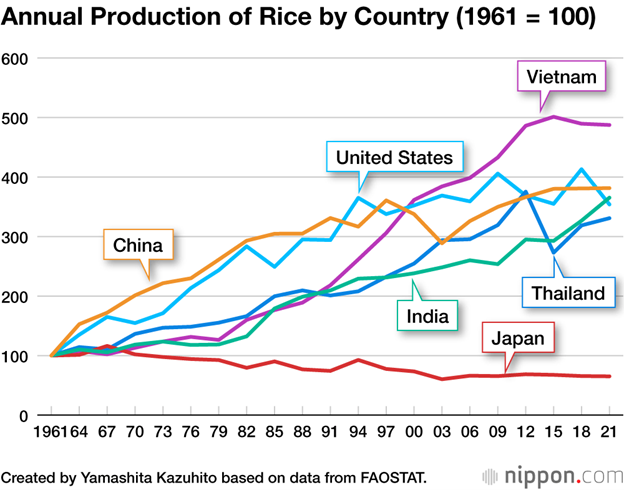

When government agencies restrict the amount of rice grown, and bad weather happens, the production is further depressed. Yamashita explains that 40 percent of available paddy fields are not currently being used; the government is restricting rice production to a cap of about 6.5 million tons. The same article contains a useful chart showing how every other major rice producing country is seeing increases in production, while Japan alone declines. (See figure below)

Yamashita explains that “[i]f Japan abandoned the acreage reduction program, it could produce 17 million tons of rice each year, with 7 million tons for domestic consumption and 10 million tons for export,” which would provide enough of a cushion to handle bad production seasons and domestic demand fluctuations.

This information is easily found, even if you are not familiar with Japanese agricultural policy. The fact that the FAO data clearly show yields increasing even as production has declined should have sent up alarm bells for the author of the El País article.

El País also claims that climate change is causing coffee production in Brazil to decline. Climate Realism debunked this claim in a previous post, “Wrong Again, Grist, Climate Change Is Not Causing Higher Coffee Prices,” which shows how coffee production has some bad years, but overall even Brazilian coffee yields have been increasing over time. This is ironic, since the El País author says that the ideal of “continuous growth” is not living up to reality.

In fact, with regards to food production, the only thing that is not living up to reality is alarmists’ predictions of climate change induced declines in production.

El País goes on to highlight a loss of drinking water in Montevideo, Uruguay. But this was due to a severe drought that has since ended. That drought was accompanied by record cold, driven by La Niña conditions in the Pacific, which are natural and known to cause dry conditions in Uruguay even as it gives more rainfall to the northeastern parts of South America. There is no long-term pattern of drought in Uruguay, and no evidence of a climate change fingerprint on drinking water shortages there.

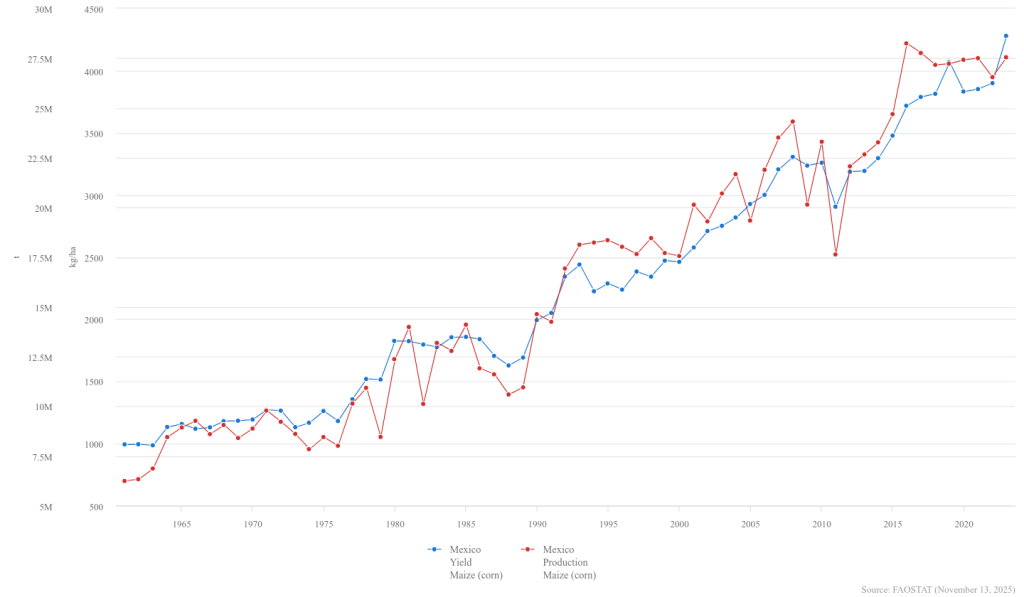

In Mexico, El País says that “white corn” production has dwindled and is “no longer sufficient to meet domestic demand.” But FAO data show that general corn production has increased 341 percent in Mexico since 1961, with a record breaking year as recently as 2016. (See figure below)

Perhaps the “dwindling” production is just the plateaued production since that peak, but all-time high yields occurred in 2023. So, the question is whether this is climate related or economics.

Corn prices have been very low recently, to the point that farmers just this year protested the Mexican government to get price guarantees on their product. Mexico News Daily reports that farmers say “production costs have increased in recent years, but prices for agricultural goods haven’t kept pace.”

Just like with Japan, when economic and political conditions make growing food more difficult and a naturally bad season strikes resulting in a decline in production, it can be more devastating to farmers and consumers than it would have been otherwise. This is not evidence of climate change hurting food production. The fact that production inputs like fertilizers are increasing in cost is, in fact, more attributable to the climate alarmists’ war on fossil fuels than anything else. Natural gas and oil are used to make and as components of fertilizers and pesticides, and power most farm equipment, like tractors, combines, and trucks.

The article makes an absurd claim, citing a study in Nature, that “a 1°C increase in average global temperature reduces food production by about 120 kilocalories per person per day.”

If that were true, we would already have seen it, as the planet has warmed more than a degree since the pre-industrial period, and in some places like Europe, even more so. Yet, global staple food production has increased, and hunger and malnutrition have decreased amid the modest warming of the past century, and especially recent decades. Part of this is due to improvements in technology, usually driven by fossil fuel use and byproducts, but also due to better growing conditions, slightly more precipitation, and the fertilizing effect of increased carbon dioxide itself, all factors discussed in Climate at a Glance: Crop Production.

To conclude, El País makes a number of false claims about short-term shortages of various crops being due to climate change. In fact, the evidence shows that government policies have limited the production of some crops, despite favorable climate conditions boosting yields. Short-term weather events have harmed production seasonally on occasion, only for subsequent years’ weather to result in better crop production. In the end, data clearly show that food production is not suffering due to climate change.

This tired claim gets harder for alarmists to defend every year as food production continues to improve. If developing countries choose to ignore climate alarmists, including El País writers who sinisterly claim that “global food production is one of the main causes of climate change,” and allow and encourage their farmers to embrace modern high-yield production techniques, including by expanding their use of fossil fuel powered or derived farm technologies, they are likely to also greatly improve crop production as well as resilience in the face of natural weather events.