By TODD MYERS

Smoke from forest fires filled the air in Western Washington and immediately the finger of blame was pointed at climate change. Prior to the recent fires, the 2020 fire season had been extremely quiet. No matter how the season ends, however, blaming climate change is politics, not science.

Not all the lands burned in the last week are forests, but forestland is a major source of the smoke we are seeing. The science is quite clear that timber harvests – including commercial timber harvests – are necessary to reduce the number of fire-prone, unhealthy forests.

The state Department of Natural Resources notes that, “We have a forest health crisis in our state. And because of our forest health crisis, we are seeing more catastrophic wildfires.” In their forest health plan, they note, “commercial timber harvesting will be an essential component of restoration efforts.” There is a lot of work to be done in our forests to get them to the point where they are fire resistant.

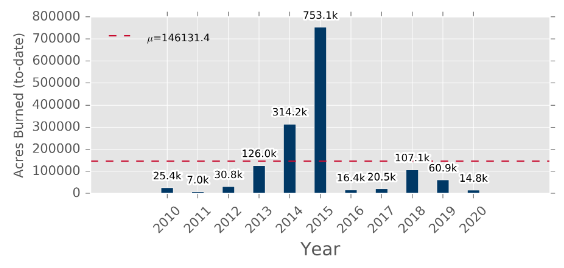

In recent years, Governor Inslee also recognized this. In his first term, he set a goal to “Increase the average annual statewide treatment of forested lands for forest health and fire reduction from 145,000 to 200,000 acres by 2017.” How did the state do? We don’t know, because the goal was removed from Results Washington when it was clear the state would probably not hit the target.

In September 2016, the Department of Natural Resources confirmed they were not on target to administer the desired forest health treatments in Eastern Washington.

Today, Results Washington lists no forest health goals, but simply says, “Washington is working to restore forests and enhance forest resiliency to severe wildfires, drought, and insect and disease outbreaks.”

No single management strategy will address all these fires. For timber-related fires, however, it is clear that poor forest health is playing a bigger role than climate change. Unfortunately, it is clear that dealing with unhealthy forests is not a priority.

Instead, the governor and other politicians point to climate change as the primary cause of the fires, focusing their efforts on climate policy. This is not only poor policy, blaming climate change for the fires we are experiencing is dubious.

A look at temperature and precipitation data show a poor correlation to the intensity of fire seasons. Using Yakima as a surrogate for temperatures in E. Washington, the average temperature this summer is just over 72 degrees. Each of the last two years saw average temperatures of just over 71 degrees. In 2017, however, the average temperature was over 75 degrees. (If you want to use another location, like Omak or Colville, you can use these links and check the history.)

The largest number of acres burned in the past five years was in 2018, when temperatures in E. Washington were cooler than this year. By way of contrast, 2017 was an extremely quiet fire year, but average temperature was 3 degrees warmer than the busy 2018 fire season.

The largest number of acres burned in the past five years was in 2018, when temperatures in E. Washington were cooler than this year. By way of contrast, 2017 was an extremely quiet fire year, but average temperature was 3 degrees warmer than the busy 2018 fire season.

Additionally, 2014 was an extremely bad fire year, but average Summer temperatures were lower than the very quiet year of 2017. Precipitation was also very similar.

Simply pointing to temperatures and even precipitation obviously doesn’t tell the whole story, nor is it a useful surrogate for fire activity.

While blaming climate change is a useful political ploy, it distracts from a policy approach that can actually reduce catastrophic fire. Even if the United States meets the most aggressive climate targets, the total impact on global temperatures would be a fraction of a degree by 2100. Given that temperatures can vary from summer to summer by several degrees, the most aggressive climate policy will do nothing to stop the fires.

Thinning, however, can yield benefits in the near future. Focusing on climate change but ignoring harvests in unhealthy forests is backwards and distracts from solutions that are necessary to prevent more smoky summers.

Watch Todd’s recent video on YouTube: Forest Fires and Climate Change with Todd Myers