https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-16941-y

Scientists’ warning on affluence

Nature Communications volume 11, Article number: 3107 (2020) Cite this article

Abstract

For over half a century, worldwide growth in affluence has continuously increased resource use and pollutant emissions far more rapidly than these have been reduced through better technology. The affluent citizens of the world are responsible for most environmental impacts and are central to any future prospect of retreating to safer environmental conditions. We summarise the evidence and present possible solution approaches. Any transition towards sustainability can only be effective if far-reaching lifestyle changes complement technological advancements. However, existing societies, economies and cultures incite consumption expansion and the structural imperative for growth in competitive market economies inhibits necessary societal change.

Introduction

Recent scientists’ warnings confirm alarming trends of environmental degradation from human activity, leading to profound changes in essential life-sustaining functions of planet Earth1,2,3. The warnings surmise that humanity has failed to find lasting solutions to these changes that pose existential threats to natural systems, economies and societies and call for action by governments and individuals.

The warnings aptly describe the problems, identify population, economic growth and affluence as drivers of unsustainable trends and acknowledge that humanity needs to reassess the role of growth-oriented economies and the pursuit of affluence1,2. However, they fall short of clearly identifying the underlying forces of overconsumption and of spelling out the measures that are needed to tackle the overwhelming power of consumption and the economic growth paradigm4.

This perspective synthesises existing knowledge and recommendations from the scientific community. We provide evidence from the literature that consumption of affluent households worldwide is by far the strongest determinant and the strongest accelerator of increases of global environmental and social impacts. We describe the systemic drivers of affluent overconsumption and synthesise the literature that provides possible solutions by reforming or changing economic systems. These solution approaches range from reformist to radical ideas, including degrowth, eco-socialism and eco-anarchism. Based on these insights, we distil recommendations for further research in the final section.

Affluence as a driver of environmental and social impacts

The link between consumption and impacts

There exists a large body of literature in which the relationship between environmental, resource and social impacts on one hand, and possible explanatory variables on the other, is investigated. We review and summarise those studies that holistically assess the impact of human activities, in the sense that impacts are not restricted to the home, city, or territory of the individuals, but instead are counted irrespective of where they occur. Such an assessment perspective is usually referred to as consumption-based accounting, or footprinting5.

Allocating environmental impacts to consumers is consistent with the perspective that consumers are the ultimate drivers of production, with their purchasing decisions setting in motion a series of trade transactions and production activities, rippling along complex international supply-chain networks5. However, allocating impacts to consumers does not necessarily imply a systemic causal understanding of which actor should be held most responsible for these impacts. Responsibility may lie with the consumer or with an external actor, like the state, or in structural relations between actors. Scholars of sustainable consumption have shown that consumers often have little control over environmentally damaging decisions along supply chains6, however they often do have control over making a consumption decision in the first place. Whilst in Keynesian-type economics consumer demand drives production, Marxian political economics as well as environmental sociology views the economy as supply dominated7. In this paper, we highlight the measurement of environmental impacts of consumption, while noting that multiple actors bear responsibility.

…

Trends

…

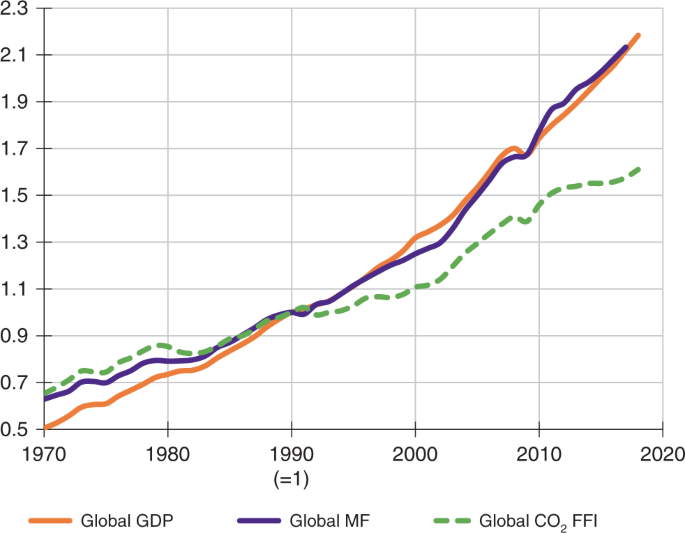

The majority of studies agree that by far the major drivers of global impacts are technological change and per-capita consumption11. Whilst the former acts as a more or less strong retardant, the latter is a strong accelerator of global environmental impact. Remarkably, consumption (and to a lesser extent population) growth have mostly outrun any beneficial effects of changes in technology over the past few decades. These results hold for the entire world22,23 as well as for numerous individual countries11,24,25,26. Figure 1 shows the example of changes in global-material footprint and greenhouse-gas emissions compared to GDP over time. The overwhelming evidence from decomposition studies is that globally, burgeoning consumption has diminished or cancelled out any gains brought about by technological change aimed at reducing environmental impact11.

Shown is how the global material footprint (MF, equal to global raw material extraction) and global CO2 emissions from fossil-fuel combustion and industrial processes (CO2 FFI) changed compared with global GDP (constant 2010 USD). Indexed to 1 in 1990. Data sources: https://www.resourcepanel.org/global-material-flows-database, http://www.globalcarbonatlas.org and https://data.worldbank.org.

Furthermore, low-income groups are rapidly occupying middle- and high-income brackets around the world. This can potentially further exacerbate the impacts of mobility-related consumption, which has been shown to disproportionately increase with income (i.e. the elasticity is larger than one27). This means that if consumption is not addressed in future efforts for mitigating environmental impact, technological solutions will face an uphill battle, in that they not only have to bring about reductions of impact but will also need to counteract the effects of growing consumption and affluence28,29.

To avoid further deterioration and irreversible damage to natural and societal systems, there will need to be a global and rapid decoupling of detrimental impacts from economic activity. Whilst a number of countries in the global North have recently managed to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions while still growing their economies30, it is highly unlikely that such decoupling will occur more widely in the near future, rapidly enough at global scale and for other environmental impacts11,17. This is because renewable energy, electrification, carbon-capturing technologies and even services all have resource requirements, mostly in the form of metals, concrete and land31. Rising energy demand and costs of resource extraction, technical limitations and rebound effects aggravate the problem28,32,33. It has therefore been argued that “policy makers have to acknowledge the fact that addressing environmental breakdown may require a direct downscaling of economic production and consumption in the wealthiest countries”17,p.5. We will address this argument in the section on systemic drivers and possible solutions.

…

Reducing overconsumption

Since the level of consumption determines total impacts, affluence needs to be addressed by reducing consumption, not just greening it17,28,29. It is clear that prevailing capitalist, growth-driven economic systems have not only increased affluence since World War II, but have led to enormous increases in inequality, financial instability, resource consumption and environmental pressures on vital earth support systems42. A suitable concept to address the ecological dimension is the widely established avoid-shift-improve framework outlined by Creutzig et al.43. Its focus on the end-use service, such as mobility, nutrition or shelter, allows for a multi-dimensional analysis of potential impact reductions beyond sole technological change. This analysis can be directed at human need satisfaction or decent living standards—an alternative perspective put forward for curbing environmental crises44,45. Crucially, this perspective allows us to consider different provisioning systems (e.g. states, markets, communities and households) and to differentiate between superfluous consumption, which is consumption that does not contribute to needs satisfaction, and necessary consumption which can be related to satisfying human needs. It remains important to acknowledge the complexities surrounding this distinction, as touched upon in the sections on growth imperatives below. Still, empirically, human needs satisfaction shows rapidly diminishing returns with overall consumption45,46.

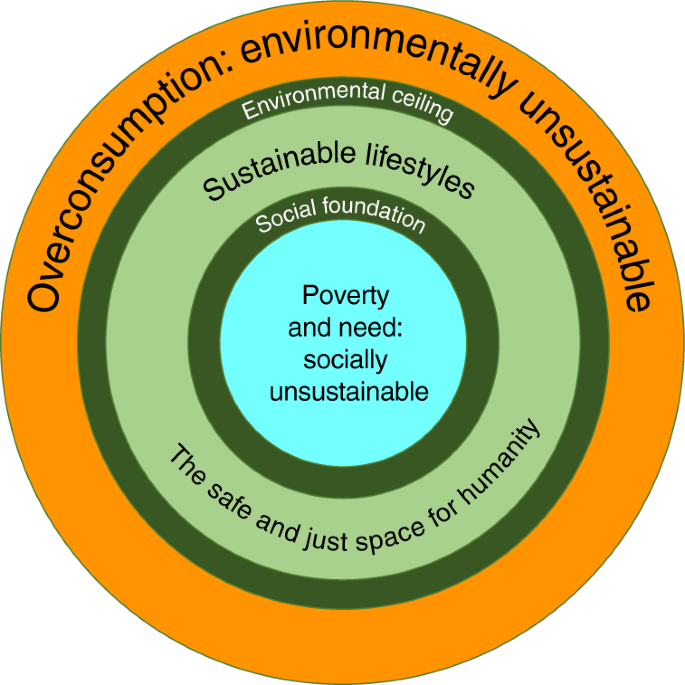

As implied by the previous section on affluence as a driver, the strongest pillar of the necessary transformation is to avoid or to reduce consumption until the remaining consumption level falls within planetary boundaries, while fulfilling human needs17,28,46. Avoiding consumption means not consuming certain goods and services, from living space (overly large homes, secondary residences of the wealthy) to oversized vehicles, environmentally damaging and wasteful food, leisure patterns and work patterns involving driving and flying47. This implies reducing expenditure and wealth along ‘sustainable consumption corridors’, i.e. minimum and maximum consumption standards48,49 (Fig. 2). On the technological side, reducing the need for consumption can be facilitated by changes such as increasing lifespans of goods, telecommunication instead of physical travel, sharing and repairing instead of buying new, and house retrofitting43.

However, the other two pillars of shift and improve are still vital to achieve the socio-ecological transformation46. Consumption patterns still need to be shifted away from resource and carbon-intensive goods and services, e.g. mobility from cars and airplanes to public buses and trains, biking or walking, heating from oil heating to heat pumps, nutrition—where possible—from animal to seasonal plant-based products43,46. In some cases this includes a shift from high- to low-tech (with many low-tech alternatives being less energy intense than high-tech equivalents, e.g. clothes line vs. dryer) and from global to local47. In parallel, also the resource and carbon intensity of consumption needs to be decreased, e.g. by expanding renewable energy, electrifying cars and public transport and increasing energy and material efficiency43,46.

…

It is well established that at least in the affluent countries a persistent, deep and widespread reduction of consumption and production would reduce economic growth as measured by gross domestic product (GDP)51,52. Estimates of the needed reduction of resource and energy use in affluent countries, resulting in a concomitant decrease in GDP of similar magnitude, range from 40 to 90%53,54. Bottom-up studies, such as from Rao et al.55 show that decent living standards could be maintained in India, Brazil and South Africa with around 90% less per-capita energy use than currently consumed in affluent countries. Trainer56, for Australia, and Lockyer57, for the USA, find similar possible reductions. In current capitalist economies such reduction pathways would imply widespread economic recession with a cascade of currently socially detrimental effects, such as a collapse of the stock market, unemployment, firm bankruptcies and lack of credit50,58. The question then becomes how such a reduction in consumption and production can be made socially sustainable, safeguarding human needs and social function50,59 However, to address this question, we first need to understand the various growth imperatives of capitalist social and economic systems and the role of the super-affluent segments of society60.

Super-affluent consumers and growth imperatives

Growth imperatives are active at multiple levels, making the pursuit of economic growth (net investment, i.e. investment above depreciation) a necessity for different actors and leading to social and economic instability in the absence of it7,52,60. Following a Marxian perspective as put forward by Pirgmaier and Steinberger61, growth imperatives can be attributed to capitalism as the currently dominant socio-economic system in affluent countries7,51,62, although this is debated by other scholars52. To structure this topic, we will discuss different affected actors separately, namely corporations, states and individuals, following Richters and Siemoneit60. Most importantly, we address the role of the super-affluent consumers within a society, which overlap with powerful fractions of the capitalist class. From a Marxian perspective, this social class is structurally defined by its position in the capitalist production process, as financially tied with the function of capital63. In capitalism, workers are separated from the means of production, implying that they must compete in labour markets to sell their labour power to capitalists in order to earn a living.

Even though some small- and medium-sized businesses manage to refrain from pursuing growth, e.g. due to a low competition intensity in niche markets, or lack of financial debt imperatives, this cannot be said for most firms64. In capitalism, firms need to compete in the market, leading to a necessity to reinvest profits into more efficient production processes to minimise costs (e.g. through replacing human labour power with machines and positive returns to scale), innovation of new products and/or advertising to convince consumers to buy more7,61,62. As a result, the average energy intensity of labour is now twice as high as in 195060. As long as a firm has a competitive advantage, there is a strong incentive to sell as much as possible. Financial markets are crucial to enable this constant expansion by providing (interest-bearing) capital and channelling it where it is most profitable58,61,63. If a firm fails to stay competitive, it either goes bankrupt or is taken over by a more successful business. Under normal economic conditions, this capitalist competition is expected to lead to aggregate growth dynamics7,62,63,65.

However, two factors exist that further strengthen this growth dynamic60. Firstly, if labour productivity continuously rises, then aggregate economic growth becomes necessary to keep employment constant, otherwise technological unemployment results. This creates one of the imperatives for capitalist states to foster aggregate growth, since with worsening economic conditions and high unemployment, tax revenues shrink, e.g. from labour and value-added taxes, while social security expenditures rise60,62. Adding to this, states compete with other states geopolitically and in providing favourable conditions for capital, while capitalists have the resources to influence political decisions in their favour. If economic conditions are expected to deteriorate, e.g. due to unplanned recession or progressive political change, firms can threaten capital flight, financial markets react and investor as well as consumer confidence shrink51,58,60. Secondly, consumers usually increase their consumption in tune with increasing production60. This process can be at least in part explained by substantial advertising efforts by firms47,52,66. However, further mechanisms are at play as explained further below.

…

Solution approaches

In response to the aforementioned drivers of affluence, diverse solution approaches and strategies are being discussed47,52,76. We differentiate these as belonging to a more reformist and a more radical group (Table 1). This is based on the categorisation by Alexander and Rutherford77.

…

The reformist group consists of heterogeneous approaches such as a-growth80, precautionary/pragmatic post-growth52, prosperity42 and managing85 without growth as well as steady-state economics86. These approaches have in common that they aim to achieve the required socio-ecological transformation through and within today’s dominant institutions, such as centralised democratic states and market economies52,77.

…

The second, more radical, group disagrees and argues that the needed socio-ecological transformation will necessarily entail a shift beyond capitalism and/or current centralised states. Although comprising considerable heterogeneity77, it can be divided into eco-socialist approaches, viewing the democratic state as an important means to achieve the socio-ecological transformation51,65 and eco-anarchist approaches, aiming instead at participatory democracy without a state, thus minimising hierarchies54,87. Many degrowth approaches combine elements of the two, but often see a stronger role for state action than eco-anarchists50,51,88. Degrowth is defined here as “an equitable downscaling of throughput [that is the energy and resource flows through an economy, strongly coupled to GDP], with a concomitant securing of wellbeing“59,p7, aimed at a subsequent downscaled steady-state economic system that is socially just and in balance with ecological limits. Importantly, degrowth does not aim for a reduction of GDP per se, but rather accepts it as a likely outcome of the necessary changes78. Moreover, eco-feminist approaches highlight the role of patriarchal social relations and the parallels between the oppression of women and exploitation of nature89, while post-development approaches stress the manifold and heterogeneous visions of achieving such a socio-ecological transformation globally, especially in the global South90.

Degrowth advocates propose similar policy changes as the reformist group50,80. However, it is stressed that implementing these changes would most likely imply a shift beyond capitalism, e.g. preventing capital accumulation through dis-economies of scale and collective firm ownership, and thus require radical social change59,62,91. Eco-socialists usually focus more on rationing, planning of investments and employment, price controls and public ownership of at least the most central means of production to plan their downscaling in a socially sustainable way65,77.

Both groups agree on the crucial role of bottom-up movements to change culture and values, push for the implementation of these top-down changes and establish parts of the new economy within the old47,50. Finally, eco-anarchists do not view the state as a central means to achieve the socio-ecological transformation. Instead, they stress the role of bottom-up grassroots initiatives, such as transition initiatives and eco-villages, in prefiguring the transformation as well as cultural and value changes as a necessary precondition for wider radical change. With these initiatives scaling up, the state might get used to remove barriers and to support establishing a participatory-democratic and localised post-capitalist economy54,77.

In summary, there seems to be some strategic overlap between reformist and the more radical eco-anarchist and eco-socialist approaches, at least in the short term77. The question remains how these solution approaches help in overcoming the capitalist dynamics previously outlined, since here bottom-up and governmental action seem to be limited. It is important to recognise the pivotal role of social movements in this process, which can bring forward social tipping points through complex, unpredictable and reinforcing feedbacks92,93 and create windows of opportunity from crises77,94.

New research directions

The evidence is clear. Long-term and concurrent human and planetary wellbeing will not be achieved in the Anthropocene if affluent overconsumption continues, spurred by economic systems that exploit nature and humans. We find that, to a large extent, the affluent lifestyles of the world’s rich determine and drive global environmental and social impact. Moreover, international trade mechanisms allow the rich world to displace its impact to the global poor. Not only can a sufficient decoupling of environmental and detrimental social impacts from economic growth not be achieved by technological innovation alone, but also the profit-driven mechanism of prevailing economic systems prevents the necessary reduction of impacts and resource utilisation per se.

…

Research on governance

A number of concrete policy proposals for governance can be extracted from the literature (see also Cosme et al.76). All of these will need further scrutiny and research on their feasibility and implementation:

First, replace GDP as a measure of prosperity with a multitude of alternative indicators and be agnostic to growth. Expect likely shrinking of GDP if sufficient environmental policies are enacted. Research needs to advise on how best to monitor and report progress towards human and planetary wellbeing.

Second, empower people and strengthen participation in democratic processes and enable stronger local self-governance. Design governance and institutions to allow for social experiments, engagement and innovation. This could be trialled and organised e.g. through citizen assemblies or juries, as is demanded by Extinction Rebellion and already practised e.g. by Transition Initiatives or the Catalan Integral Cooperative92.

Third, strengthen equality and redistribution through suitable taxation policies, basic income and job guarantees and by setting maximum income levels, expanding public services and rolling back neoliberal reforms (e.g. as part of a Green New Deal79). Stronger regulation might be needed to ban certain products or ecologically destructive industries that have thrived on a legacy of vested interests, lobbying and state-supported subsidies.

Fourth, the transformation of economic systems can be supported with innovative business models that encourage sharing and giving economies, based on cooperation, communities and localised economies instead of competition. Research is needed to create, assess and revise suitable policy instruments.

And finally, capacity building, knowledge transfer and education—including media and advertising—need to be adapted to support local sufficiency projects and citizen initiatives.

#

Related:

Stephen Moore: “The degrowth fad — hopefully it is just that — also reveals the modern left movement for what it is at its core. It is anti-growth, anti-people, anti-free enterprise and anti-prosperity. The entire climate change movement is an assault against cheap and abundant energy and rising living standards. This raises the question of how we could ever rely on the left to fix our economy, help the poor and make us all more prosperous if their goal is to shrink the economy, not grow it?”

“Degrowth” involves a purposeful contraction of the economy

Some climate-focused economists see the COVID-19 pandemic as an unwitting experiment for a radical strategy to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions. The concept is called “degrowth.” It involves a planned slowdown of economic sectors that emit large amounts of global carbon dioxide. Those sectors would scale down until the broader economy meets “sustainable emissions levels,” advancing long-term health and environmental goals.

Natasha Chassagne of the University of Tasmania: There are “opportunities we can take away from the coronavirus emergency.” …

“‘Degrowth’ involves a purposeful contraction of high-emitting sectors while growing other sectors that produce low or zero emissions.”

#

STUDY in Nature: Global wealth redistribution, economic ‘degrowth’ needed to fight ‘global warming’

New study claims economic systems must be restructured to fit ‘within planetary boundaries.’ Paper urges “moving beyond the pursuit of GDP growth to embrace new measures of progress. It could also involve the pursuit of ‘degrowth’ in wealthy nations and the shift towards alternative economic models such as a steady-state economy.”

From a study in the journal Nature: “A Good Life for All Within Planetary Boundaries:” – “We apply a top-down approach that distributes shares of each planetary boundary among nations based on current population (a per capita biophysical boundary approach)…If all people are to lead a good life within planetary boundaries, then our results suggest that provisioning systems must be fundamentally restructured to enable basic needs to be met at a much lower level of resource use.”