https://www.freedom-research.org/p/interview-professor-richard-lindzen

INTERVIEW. Professor Richard Lindzen on Climate Change: Never Take Yourself So Seriously That You Have To Invent Problems

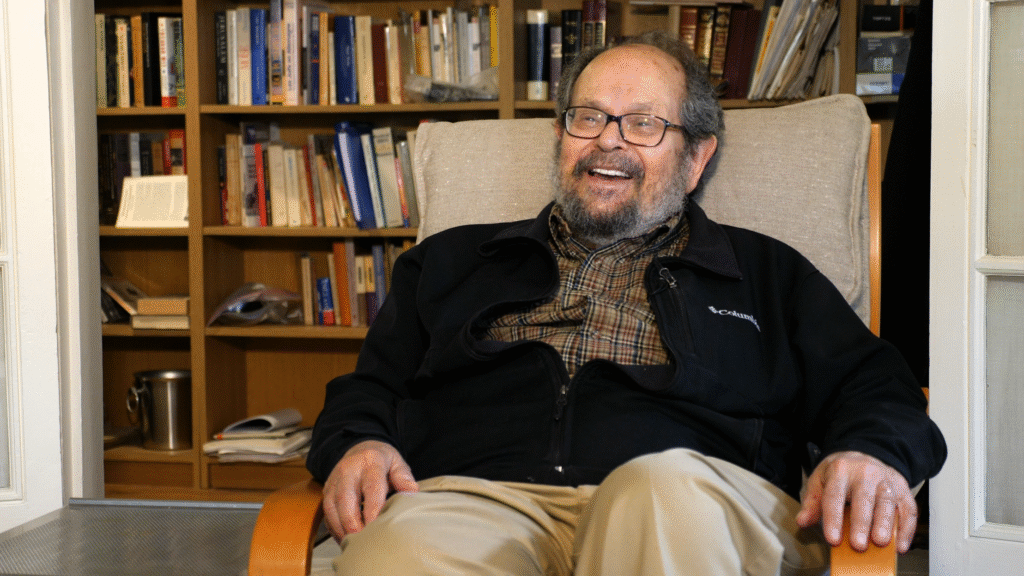

Atmospheric scientist Dr. Richard Lindzen explains in the interview that the current warming and climate change are nowhere near posing an existential threat to us.

By HANNES SARV

Excerpts:

Extreme weather linked to man-made climate change—Dr. Richard Lindzen, an atmospheric physicist and professor emeritus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), cannot think of better evidence that shows the climate crisis is a fake issue. “Issue after issue of these IPCC (UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – HS) reports, they always looked – is there any relation between extreme weather and their metric for climate. And they always find there is no statistically significant relation,” he explains.

However, some people are so concerned about the ways to push climate change and CO₂ reduction that they are going out of their minds, according to Lindzen. “They’re showing this temperature graph. And I think they’re realizing people are saying, you know, you draw it like this (going sharply up – HS), but this is one degree. That’s not much. And they’re worried: this is not getting people worried enough. So they’re saying: well, showing them a flood, showing them a storm, that would be visually convincing,” he says. And as it happens, there are always places on Earth that suffer from extreme weather in a way that occurs only once in a hundred years. “And people don’t figure it out that a once in a hundred years event is occurring some place on Earth every month, or five places every month. You have a picture of that. You now put that on television and you can associate ‘climate change’ with something dramatic,” Lindzen says. “The fact that they had to go to that to convince people suggests it was a fake issue because they’re clearly using something that would be normally called false advertising,” he adds.

In the interview, Lindzen discusses extensively what climate scientists know about climate change and its processes, as well as the half-truths and outright lies propagated by those proclaiming a climate crisis. He addresses topics such as the limited capacity of CO₂ to warm the planet and its actual role on Earth, the limited warming not actually being an existential threat to us, the absurdity of climate policies, and the future of energy.

You can watch the video version of the interview here.

Dr. Lindzen, let me start with a quote. “The fact that the developed world went into hysterics over changes in global mean temperature anomaly of a few tenths of a degree will astound future generations.” Well, you are of course familiar with the quote because it’s yours. This is from an essay that you wrote in 2009. Well, it’s now 2025.

I would have said much the same in 1990.

Really? How come?

It’s a fair question. Where did this come from? And to be honest, I don’t entirely know. Some of it began, I would say, already in 1970. In 1970 already, the environmental movement changed to an emphasis on energy. You’re too young to remember, but the first thing they were concerned with was, of course, global cooling.

Forgive me if I use this term because I think it’s a very bad term – when they speak of the Earth’s temperature, I have no idea what it means. I mean, I don’t know how you take the temperature of the Earth. Are you going to average Mount Everest with the Dead Sea?

I don’t know, but let me tell you, I’m confused because they are telling us that…

The world is warming. What are they talking about? Do you have any idea?

I guess average temperature?

No, we can’t average the Red Sea, the Dead Sea, with Mount Everest. What are they averaging?

So what are they talking about?

Ok, the formal definition these days is they are taking at each station a 30-year average, looking at the deviation from the 30-year average at that station, and that’s what they’re averaging. It’s the average change over the globe.

Then they have the satellites. They are doing something else, because they are measuring a thick layer of the lowest 10 kilometers or 5 kilometers, and so they are averaging a temperature because they don’t have a mountain, they don’t have a valley, it’s just air.

How do you compare them? I don’t know. People are throwing around numbers. You suddenly have a public, they’re listening, and they say: the temperature was up a tenth of a degree this year, and that’s a record-breaking year. And you say, I can’t tell a tenth of a degree if I take my temperature. The doctor doesn’t care if it’s 96.7 or 96.6. What are they talking about? But we’re somehow assuming a tenth of a degree matters.

And it doesn’t?

Does it matter to you? If the temperature changes a tenth of a degree now?

Well, we’re doing this interview in Paris, and today in Paris it’s quite a warm day.

Yeah, sure. But it’s 20 degrees warmer than it was in the morning, or 10 degrees centigrade. And we survived.

So when somebody says that a change of a tenth of a degree, or when Guterres says if it changes a half-degree, we’re finished as a species, this is an existential threat – people have to ask, what the hell are they talking about?

I have my thoughts as to why it is that educated people don’t ask questions. For most of my career, I’ve been a teacher. You have some students who are really very good, but most are okay. They’re not great. They’re going to have jobs, they’re going to do them reasonably well, and so on, but for them succeeding in school is mostly pleasing the professor. So, no matter how stupid the professor might be, they’ve learned to rationalize what the professor says. And so the skill that most people pick up at the university, I suspect, is the ability to rationalize any statement, no matter how ridiculous. So if somebody says a half-degree is the end of the world, they say: yeah, I can see that. The ordinary person does not have that skill. He knows a half-degree is small. You saw this with the farmers here (European farmers’ protests – HS), the truck drivers in Canada (Freedom Convoy – HS). None of them believes this stuff.

What do you think about the academic quality nowadays in the US and Europe?

We’re watching our universities self-destruct. It’s outrageous. If you look at Harvard University… I graduated from Harvard, I taught there, I was a professor for a dozen years. They had a president, Claudine Gay, who wrote 11 papers in her whole life, and most of them were copied from something else. How did this happen? At MIT, we have a president, Sally Kornbluth. I’m sure she’s a nice lady. She was a biologist at Duke University. She hasn’t the faintest idea what she’s doing. She needs to say she has some grand idea. So she’s decided the grand idea is climate. She knows nothing about climate. What is the big problem she’s dealing with? How to get the music department involved in the war on climate. I mean, it’s absolutely crazy.

…

Some decades ago, you were also working with these scientific reports.

Yes, I was working with the IPCC, and you know it was absurd. In order to write three or four pages with two other people, we traveled around the Earth two or three times. There was a meeting in New Zealand, a meeting in Nairobi. And the three of us… There was a fellow called Pierrehumbert, who’s today at Oxford (American geophysicist Raymond Pierrehumbert – HS). There was another guy from France. We all decided that we may not agree, but let’s not say anything that we know is false. So the section was on what we knew about feedbacks. And it was a completely honest section. It was biased. We were told we couldn’t attack models too much. But basically, what we wrote was honest. It said we didn’t know what we were doing.

…

So models, computer models.

Models are their own story. Models are useful. But not for prediction. The reason they’re not good for prediction is we don’t know the feedbacks, we don’t know clouds, we don’t know and resolve other things. So they cannot handle processes that are essential. They’re useful if you’re doing theory. You can look at the models and see how things interacted and then focus on those more carefully to see whether you understand the interaction. So there is a kind of back and forth between models and theory, and so on. But that isn’t how they’re used.

The issue began with having no science at all. It began, as I said, with global cooling. As long as there was some way this number, this crazy number, was showing cooling since from about 1939 to 1973, they said, well, let’s say it’s cooling. And then you had models as well – they were called the Budyko-Sellers models (after Russian and US climatologists Mikhail Budyko and William Sellers – HS). All of us liked to play with them. They were cute. They showed that if you reflected light with sulfates enough, the original version of the model would give you an ice-covered Earth. That seemed very dramatic. And then people, including us, began showing that, well, if you put in something more realistic in the tropics, it stopped there at 30 degrees. And then finally, in my course notes, I have a problem where you put into this model the change of seasons, and the model falls apart completely.

So, for the global cooling, you had the model you needed to give a scare story for cooling. But then in ’73, in the 70s, it stopped cooling. So you needed something else. What was the next thing that came up? It was, again, the energy sector. Acid rain. The forest in Germany was dying. Unfortunately, after a few years, the forest stopped dying. So, acid rain was not too useful. People tested it. They found it didn’t have much impact.

But then they noticed the temperature was increasing, and that they liked. Why did they like it? Because the reason you would give for the temperature increasing is that CO₂ was increasing. Why did they like CO₂? Well, with global cooling, you are worried about sulfate aerosols. The trouble with sulfate aerosols is we know how to clean them. We can build a coal plant that has no sulfate emissions. Well, what good is that!? CO₂ – nothing can stop that. It is the product of any burning, including breathing.

So you generate a lot of CO₂. Anything that burns a fossil fuel produces CO₂. After you clean every real pollutant out, you still have CO₂. So this was guaranteed to get rid of any fossil fuel. And that was its attraction. And that’s what we’ve gone with for the last, since ’88.

And it was interesting… You were a little surprised when I said it began many years ago. In 1988, you had a Senate hearing in the US, and you had a man called James Hansen (US climatologist – HS) testifying. He came there and said that increasing CO₂ was going to cause a lot of warming. And Newsweek had a cover showing the Earth on fire, and it had a label: “All scientists agree”. And that was very interesting, because at that time, almost no scientists were working on this. People were told all scientists agree. Now, think of that from a propaganda point of view. You don’t know science, you haven’t studied it, most people haven’t studied it. Even among the people who studied the science, for this problem, a big part of the problem is fluid mechanics. Almost no physicist ever studies fluid mechanics. So you have something that hardly anyone has studied. And you’re saying: “What am I going to do? I don’t understand this.” You are told all scientists agree. This is a source of comfort. You don’t have to understand it. If all scientists agree, you can agree, too.

We hear it more and more nowadays. That there is now a 97 per cent consensus.

Oh, that’s fake! How should I put it? It always depends on the question. So, for instance, if you asked a question if doubling CO₂ is more likely to warm than to cool the Earth, I would think you’d get 100% agreement. But that’s not the same as saying it’s a serious problem. So, at that level, if you ask the right question and put a funny interpretation on the answer, you can say all scientists agree. You just haven’t said what they agree with.

Then you have the paper by Cook that said 97% (Cook et al. 2013). They looked at journals and tried to find articles that discussed certain impacts of climate. And so they looked at, don’t take my numbers seriously – they looked at 1,000 articles, they found 40 articles that spoke about certain impacts. And for those 40 articles, they found 97% said so, and so they said 97% said that. But it was like a few percent of the total (the case was even worse: it was ca 40 out of ca 12,000 – HS).

What is your opinion on this phrase itself: consensus, scientific consensus? Is it something that science is made of? Is it made of consensus?

No, of course not. Whenever you hear consensus science, you know something is wrong. So, for instance, you know, this was in the Soviet Union with (agronomist Trofim – HS) Lysenko. Yes, there was a consensus in favor of his view of evolution, because if you disagreed, you went to the GULAG. It’s a powerful argument?!

Today, it’s equally true if you’re teaching. If you’re not part of the consensus, you don’t get paid. It’s better than the GULAG, but, you know… .

What is the state of climate science and climate teaching in the university?

It’s horrible. First of all, there is so much money thrown at climate. As I mentioned to you, when the issue began in public in ’88, you had very few departments and very few people working on climate. All of a sudden, when the government is providing money, when the UN and the EU are providing money, every university now has a climate group. It doesn’t advance the subject because no one is permitted to actually study it. If you actually studied it, you would see this makes no sense.

We actually wrote a paper about a year ago, trying to address the question – why do you argue that a degree, one degree, is important? And if you pressure people who are working on it, they will say something like, there is polar amplification. That whatever you do in the tropics is amplified at the poles. For people who worked on the theory, they know this isn’t true. What determines the temperature difference between the tropics and the pole is the fluid mechanics that produces the high and low pressure areas that you see on your weather map. And they carry heat to the pole, and they determine the temperature difference. It’s not an amplification of the tropics. But you can at least ask the question – does the data show that it is? And what we were able to show is that in the data from about the early 19th century to the present, there is no polar amplification. So all that you’re getting is that half-degree, that one degree. One degree every place is all the contribution from greenhouse. And for practical purposes, this is much smaller than the actual climate change that has occurred. The Gulf Coast of the US has gotten much colder. That is a change. But it doesn’t reflect itself in the equator to pole, tropics to pole, it’s local. And in fact, most of the climate change associated with time scales from about three or four years for El Niño to a thousand years, let’s say the medieval warm period, are probably due to the ocean. The ocean is much denser than the atmosphere, obviously, and as a result, its circulations take much longer. They involve much more mass. And so ocean circulations, depending on their depth, they’re up to a thousand years. And what happens? You have circulations that are taking heat away from the surface and bringing heat to the surface. So the surface is never in equilibrium with space, which is the basis of a lot of the simple discussions. It’s always changing the surface, but it changes it locally. Different ocean currents are peculiar to different regions of the ocean.

We know that the Earth has many different climates already. The climate in the Sahara is different from the Mediterranean coast, is different from Scandinavia, is different from the Baltics, and so on. But if you look at each region, let’s say Tallinn and London, or Tallinn and New York, the changes don’t correlate. They’re each different. And so you have a world where climate change is occurring always, and on time scales that we’re looking at, like the medieval warm period, the Little Ice Age, and so on, it’ll be very hard to understand because it’ll involve all the details of the ocean interacting with the air. You then have the big changes. The last glacial maximum, when half of North America was covered in two kilometers of ice, and you have the Fennoscandian ice, and so on.

You also have 50 million years ago, the Eocene, when you had alligators or like alligators in Spitsbergen. Those involved the changes in temperature from the tropics to the pole. That depends on fluid mechanics, it’s internal, and it depends on surface conditions. By that I mean, you know, if you have ice or snow on the surface, it changes the response at the surface to the waves, the highs and the lows. It’s somewhat complicated, but people have worked it out. There are papers that have done this. They’re very hard to follow. This has been true for a long time. Do you know the name Werner Heisenberg?

…

What happens if I get rid of about 60-65% of the CO₂ in the atmosphere? Do you have any idea?

We’ll die. We’ll die of starvation. At 160 parts per million, virtually no plant will survive. No plant survives, there’s no food.

…

But let me ask a simple question, because I don’t think people even understand. What happens if I get rid of about 60-65% of the CO₂ in the atmosphere? Do you have any idea?

No, I don’t. I have a suspicion. I suspect that it is not going to be very good for nature.

Forget the nature. How about us? We’ll die. We’ll die of starvation. At 160 parts per million, virtually no plant will survive. No plant survives, there’s no food.

So CO₂ is very important, but it’s demonized irrationally, and really, I’m puzzled. I cannot get it to my head. Why is it done?

I think for the same reason that years ago, as a joke, someone asked people, is it a good idea to get rid of H₂O? They said, yes, it’s a chemical. We get rid of chemicals!

Some people still use the word climate crisis to describe today’s situation, or at least say that we are heading towards a climate crisis.

What is a climate crisis?

That’s what I wanted to ask.

I don’t know. I mean, they often give you a picture of New York underwater.

It would be a crisis.

It would be a crisis if it were true. But even if it were true, how shall I put it? We’re talking about thousands of years. A thousand years ago, what was in New York? Nothing. You had the geography, there were some Native Americans living there, but nothing special. A thousand years from now, who knows? But it’s perfectly clear that if the coast of the U.S. were 40 miles inland from today, the U.S. would still be a viable country. And instead of New York, you would have Philadelphia or Chicago.

I don’t know how to talk about a thousand years from now. And nobody 300 years ago knew how to talk about today.

There is a lot of talk about those tipping points. They are saying that if the temperature rises, small changes will bring big consequences.

It’s a statement that if you go beyond a certain limit, you then leap. This is a property mostly of systems that have what are called very few degrees of freedom. So when you have a system that has very few possibilities, then if you push it too hard, it has to jump to something. This is not a property of a continuous system like climate. The climate does not go through tipping points. This is an artifact that people who want to generate a scare story throw out. And if you’re not a scientist, you say, gee, what is this tipping point? But it’s not for a system that is continuous. It’s for a system that has no choice. Our system has lots of choices.

You mentioned extreme weather events. This is a claim that is being made, the crisis is linked to extreme weather events.

I think there’s no better evidence that this is a fake issue. Issue after issue of these IPCC reports, they always looked – is there any relation between extreme weather and their metric for climate. And they always find there is no statistically significant relation. In the meantime, you have the people who are pushing climate change and CO₂ reduction, and they’re going out of their minds. How can they convince people to get worried? And so they’re showing this temperature graph. And I think they’re realizing, people are saying, you know, you draw it like this (going sharply up – HS), but this is one degree. That’s not much. And they’re worried: this is not getting people worried enough. So they’re saying: well, showing them a flood, showing them a storm, that would be visually convincing.