https://www.breakthroughjournal.org/p/why-i-stopped-being-a-climate-catastrophist

By Ted Nordhaus

Excerpt: Recently, in an exchange on X, my former colleague Tyler Norris observed that over the years, my views about climate risk have evolved substantially. Norris posted a screenshot of a page from the book Break Through, where Michael Shellenberger and I argued that if the world kept burning fossil fuels at current rates, catastrophe was virtually assured:

Over the next 50 years, if we continue to burn as much coal and oil as we’ve been burning, the heating of the earth will cause the sea levels to rise and the Amazon to collapse, and, according to scenarios commissioned by the Pentagon, will trigger a series of wars over the basic resources like food and water.

Norris is right. I no longer believe this hyperbole. Yes, the world will continue to warm as long as we keep burning fossil fuels. And sea levels will rise. About 9 inches over the last century, perhaps another 2 or 3 feet over the course of the rest of this century. But the rest of it? Not so much.

There is little reason to think that the Amazon is at risk of collapsing over the next 50 years. Agricultural yield and output will almost certainly continue to rise, if not necessarily at the same rate as it has over the last 50 years. There has been no observable increase in meteorological drought globally that might trigger the resource wars that the Pentagon was scenario planning back then.

At the time that we published Break Through, I, along with most climate scientists and advocates, believed that business as usual emissions would lead to around five degrees of warming by the end of this century. As Zeke Hausfather, Glen Peters, Roger Pielke Jr, and Justin Richie have demonstrated over the last decade or so, that assumption was never plausible.

There have been some revisionist claims that the reason for the downgrading of business as usual warming assumptions is due to the success of climate and clean energy policies over the last several decades. But five degrees of warming by the end of this century was no more plausible in 2007, when Break Through was published, than it is today. The class of scenarios upon which it was based assumed very high population growth, very high economic growth, and slow technological change. None of these trends individually track at all with actual long term global trends. Fertility rates have been falling, global economic growth slowing, and the global economy decarbonizing for decades.

Nor is there good reason to think that the combination of these three trends could possibly be sustained in concert. High economic growth is strongly associated with falling fertility rates. Technological change is the primary driver of long term economic growth. A future with low rates of technological change is not one that is consistent with high economic growth. And a future characterized by high rates of economic growth is not one that is consistent with high rates of population growth.

As a result of these dynamics, most estimates of worst case warming by the end of the century now suggest 3 degrees or less. But as consensus around these estimates has shifted, the reaction to this good news among much of the climate science and advocacy community has not been to become less catastrophic. Rather, it has been to simply shift the locus of catastrophe from five to three degrees of warming. Climate advocates have arguably become more catastrophic about climate change in recent years, not less.

This is all the more confounding given that the good news extends well beyond projections of long term warming. Despite close to a degree and a half of warming over the last century or so, global mortality from climate and weather extremes has fallen by a factor of 25 or more on a per capita basis. As Pielke documented recently, the world is on track this year for what is almost certainly the lowest level of climate related mortality in recorded human history, not only on a per capita basis but on an absolute basis as well. The economic costs of climate extremes continue to rise, but this is almost entirely due to affluence, population growth, and the migration of global populations towards climate hazards, mainly cities that tend to be located in coastal regions and flood plains.

So I think the far more interesting question that Norris raises, at least implicitly, is not why my colleagues and I at Breakthrough have revised our priors about climate risk but why so many progressive environmentalists like Norris have not.

When Is Weather Climate Change?

For me, the cognitive dissonance began as I became familiar with Roger Pielke Jr’s work on normalized hurricane losses, in the late 2000s. This was around the time that a lot of messaging from the climate advocacy community had started to focus on extreme weather events, not just as harbingers for the storms of our grandchildren, to borrow the title of James Hanson’s 2009 book, but as being fueled by climate change in the present.

Hanson himself had been under no such illusion, writing that “local climate change remains small compared with day-to-day weather fluctuations.” But by this point, the advocacy community had figured out that framing climate change as a future risk would not prove sufficient politically to transform the US and global energy systems in the way that most believed necessary. This became a particularly urgent concern for the movement after the failure of the Waxman-Markey cap and trade legislation in 2010. And so the movement set about attempting to move the locus of climate catastrophe from the future to the present.

If you want to know why Pielke has been so demonized over the last 15 years by climate activists and activist climate scientists, it’s because he got in the way of this new narrative. Pielke’s work, going back to the mid-1990s showed, again and again, that the normalized economic costs of climate related disasters weren’t increasing, despite the documented warming of the climate. And unlike a lot of researchers who sometimes produce studies that cut against the climate movement’s chosen narratives, he wasn’t willing to be quiet about it. Pielke got in the way of the advocacy community at the moment that it was determined to argue that present day disasters were driven by climate change and got run over.

But the cognitive dissonance for me went well beyond that. It wasn’t just that Pielke had produced strong evidence that undermined a key claim of the climate advocacy community. It wasn’t even witnessing Pielke’s cancellation, which was brutal. It came, rather, as I came to understand why you couldn’t find a climate change signal in the disaster loss data, despite close to a degree and a half of warming over the last century or so.

That comes down to two linked factors that determine how climate becomes weather and, in turn, how weather contributes to climate related natural disasters. Taking the second of these first, climate related natural disasters are not simply the result of bad weather. They happen at the intersection of weather and human societies. What determines the cost of a climate related disaster, in both human and economic terms, is not just how extreme the weather is. It is also how many people and how much wealth is affected by the extreme weather event and how vulnerable they are to that event. Over the same period that the climate has warmed by 1.5 degrees, the global population has more than quadrupled, per capita income has increased by a factor of ten, and the scale of infrastructure, social services, and technology that protect people and wealth from climate extremes has expanded massively. These latter factors simply overwhelm the climate signal.

But it’s not just that these other factors—exposure and vulnerability to climate hazards—are such huge factors in determining the costs of climate related disasters. Hence, the second problem with claims that climate change causes natural disasters is that anthropogenic climate change is simply a much smaller factor at the local and regional scale than natural climate variability. There is nothing in the climate science literature that has changed this basic fact since Hanson made the same observation over 15 years ago.

Over the last several years, some climate scientists, including Hausfather and Hanson, have pointed to anomalously high surface and ocean temperatures as evidence that warming may be accelerating, perhaps even faster than model ensembles have suggested. But even in the case where climate sensitivity proves to be relatively high, additional anthropogenic warming is an order of magnitude less than the oscillations of natural variability.

This basic physical reality can get lost in the enormous climate impacts literature, with its confusing terminology and findings around concepts like attribution and detection. Arguments about whether anthropogenic climate change has had any impact on extreme events of various sorts quickly get mixed up with arguments about whether climate change is a major factor, much less the major factor in extreme events.

…

A Sting in the Tail?

For a long time, even after I had come to terms with the fundamental disconnect between what climate advocates were saying about extreme events and the role that climate change could conceivably be playing, I held on to the possibility of catastrophic climate futures based upon uncertainty. The sting, as they say, is in the tail, meaning so-called fat tails in the climate risk distribution. These are tipping points or similar low probability, high consequence scenarios that aren’t factored into central estimates. The ice sheets could collapse much faster than we understand or the gulf stream might shut down, bringing frigid temperatures to western Europe, or permafrost and methane hydrates frozen in the sea floor might rapidly melt, accelerating warming.

These and many other so-called tipping points commonly invoked as reason for precaution are the known unknowns of climate risk—specific phenomena that we know might happen without being able to specify very precisely their probability and magnitude, the timeframe over which they might occur, or the threshold of warming and other factors that might trigger them.

…

Finally, there is a widespread belief that one can’t make a strong case for clean energy and technological innovation absent the catastrophic specter of climate change. “Why bother with nuclear power or clean energy if climate change is not a catastrophic risk,” is a frequent response. And this view simply ignores the entire history of modern energy innovation. Over the last two centuries, the world has moved inexorably from dirtier and more carbon intensive technologies to cleaner ones. Burning coal, despite its significant environmental impacts, is cleaner than burning wood and dung. Burning gas is cleaner than coal. And obviously producing energy with wind, solar, and nuclear is cleaner than doing so with fossil fuels.

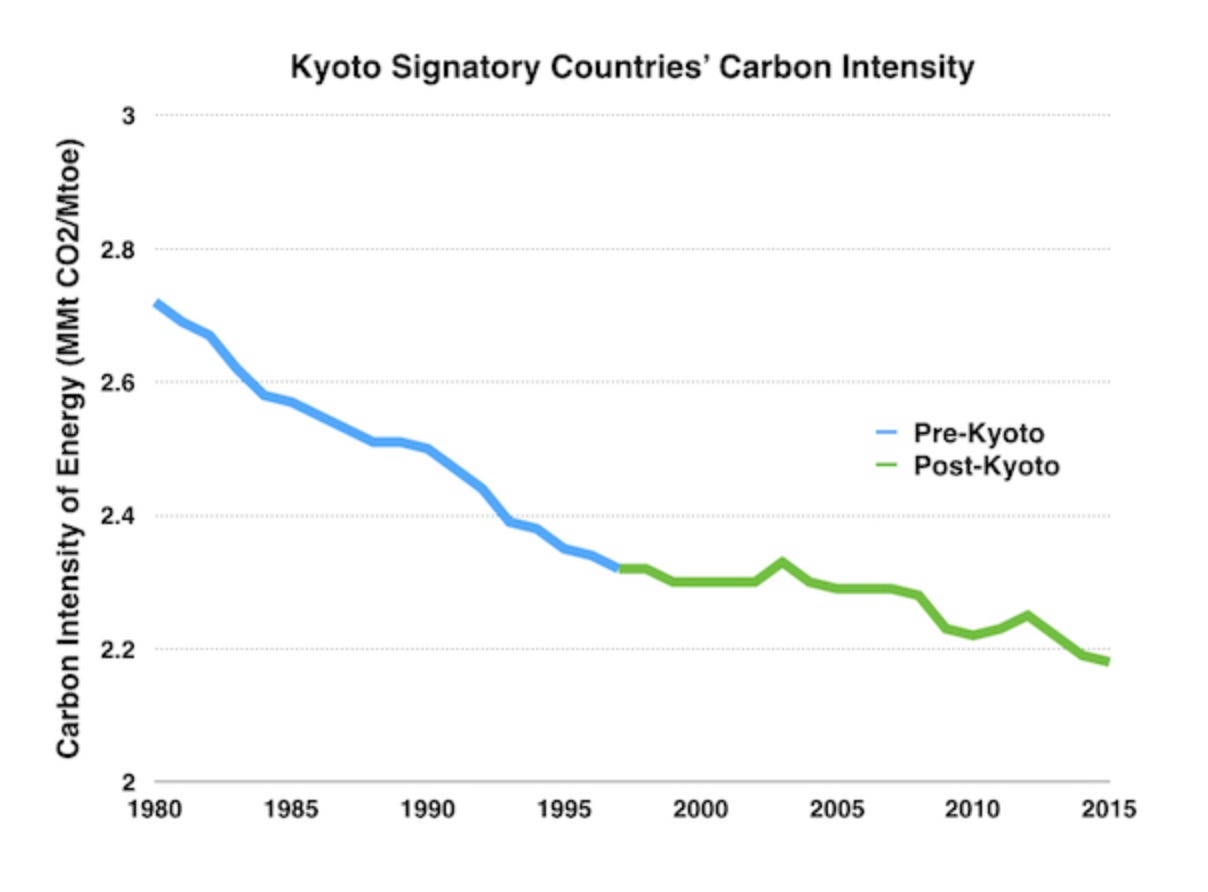

There is a view among most climate and clean energy advocates that the risk of climate change both demands and is necessary to justify a much faster transition toward cleaner energy technologies. But as a practical matter, there is no evidence whatsoever that 35 years of increasingly dire rhetoric and claims about climate change have had any impact on the rate at which the global energy system has decarbonized and by some measure, the world decarbonized faster over the 35 years prior to climate change emerging as a global concern than it did in the 35 years since.

This argument ultimately becomes circular. It’s not that there is no reason to support cleaner energy absent fear of catastrophic climate change. It’s that there is no reason to support a rapid transformation of the global energy economy at the speed and scale necessary to avoid catastrophic climate change if the specter of catastrophic climate change is not looming. Which is arguably true but is also a proposition that depends upon not asking particularly hard questions about the nature of climate risk.

Despite some tonal, tactical, and strategic differences, this basic view of climate risk, and corresponding demand for a rapid transformation of the global energy economy is broadly shared by the climate activists and the pragmatists. The impulse is millenarian, not meliorist. Underneath the real politik, technocratic wonkery, and appeals to scientific authority is a desire to remake the world.

For all its worldly and learned affect, what that has resulted in is the creation of an insular climate discourse on the Left that may be cleverer by half than right wing dismissals of climate change but is no less prone to making misleading claims about the subject, ignoring countervailing evidence, and demonizing dissent. And it has produced a politics that is simultaneously grandiose and maximalist and, increasingly, deeply out of touch with popular sentiment.