A weird lack of Northern Hemisphere tropical cyclones so far in 2025

by BOB HENSON and JEFF MASTERS

Flash floods have been front and center in this month’s U.S. weather picture, while tropical cyclones have been mostly lying low, as we discussed in our July 18 Eye on the Storm post. The year’s fourth named storm of the Atlantic season has only low odds of developing this week from a bubbling disturbance in the tropical Atlantic, and it looks unlikely to become a serious threat to land even if it does get organized.

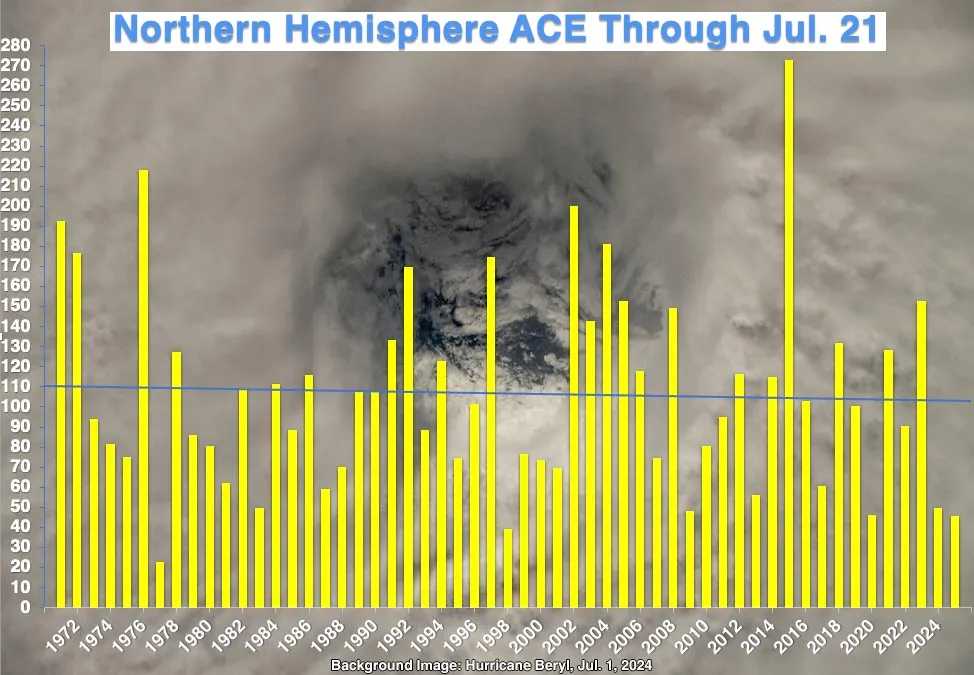

It’s not just the Atlantic that’s been quiet. Each of the four basins of the Northern Hemisphere that generate tropical cyclones — the Atlantic, Northeast Pacific, Northwest Pacific, and North Indian Oceans — is now running below average on accumulated cyclone energy, or ACE, a function of peak wind speeds and storm longevity. For the hemisphere as a whole, the total ACE to date is the third-lowest in records dating back more than half a century.

The graph above shows Northern Hemisphere ACE for each year from January 1 through July 21, starting with 1971, the first year of reliable data from the Northeast Pacific. The ACE to date of 45.5 is only about 41% of the climatological average for the period 1991-2020. The only years with lower ACE at this point were 1977 (23.0) and 1998 (39.1).

The table below, from the Real-Time Global Tropical Cyclone Activity page maintained by Colorado State University, shows how each basin on Earth is faring on various measures of tropical cyclone activity. The Northern Hemisphere hasn’t been slack in producing named storms: the total of 16 thus far is actually at the year-to-date average. It’s just that the systems that do develop haven’t been surviving long or intensifying much. The cumulative longevity of each named storm (or “named storm days” in the table below) is only about two-thirds of average. As for hurricane-strength systems — which are called typhoons in the Northwest Pacific and severe cyclonic storms in the North Indian Ocean — their cumulative longevity is a mere 27% of average.

Surprising at it may seem, given how active the Atlantic has been over the past 30 years, the total number of tropical cyclones on Earth hasn’t increased in recent decades, although the strongest hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones are getting more intense on average.

In its 2021 assessment, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded that these trends are liable to continue:

- “the proportion of Category 4-5 TCs [tropical cyclones] will very likely increase globally with warming”

- “it is likely that … the global frequency of TCs over all categories will decrease or remain unchanged”

Though they’re in a minority, a few researchers have found evidence in high-resolution modeling for a potential global increase in tropical cyclone numbers, including Kerry Emanuel of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.