The most influential climate activist in the world, with no runner-up in sight, is Greta Thunberg. Time Magazine named her Person of the Year for 2019 and it feels inevitable that she will win the Nobel Peace Prize eventually if not this year. With her 14 million followers on Instagram and her five million followers on Twitter, everything she does is news. Reuters named as one its key “Moments from 2021” Thunberg singing and dancing at a promotional “Climate Live” concert in advance of the United Nations climate talks.

But for all of her fame, Thunberg’s political influence has never been lower. Two weeks ago, Thunberg and other climate leaders demanded that Europe not finance either nuclear plants or natural gas production, but the European Commission rejected her demands and confirmed Saturday that both nuclear and natural gas will be counted as sustainable and thus be available for European Union financing. The EU “sustainable taxonomy” deal appears to be a compromise between nuclear-reliant France and increasingly gas-reliant Germany.

Thunberg remains powerful. Many analysts until recently thought shareholder activism aimed at forcing divestment from oil and gas production was strictly symbolic, merely a way to draw attention to the need for public policy. It’s now clear that such activism was remarkably effective in suppressing private sector financing for oil and gas exploration and production, contributing to shortages. That was, in no small measure, due to Thunberg’s extraordinary reach and emotional connection to the young, including college students, and the children of financial, journalistic, and intellectual elites.

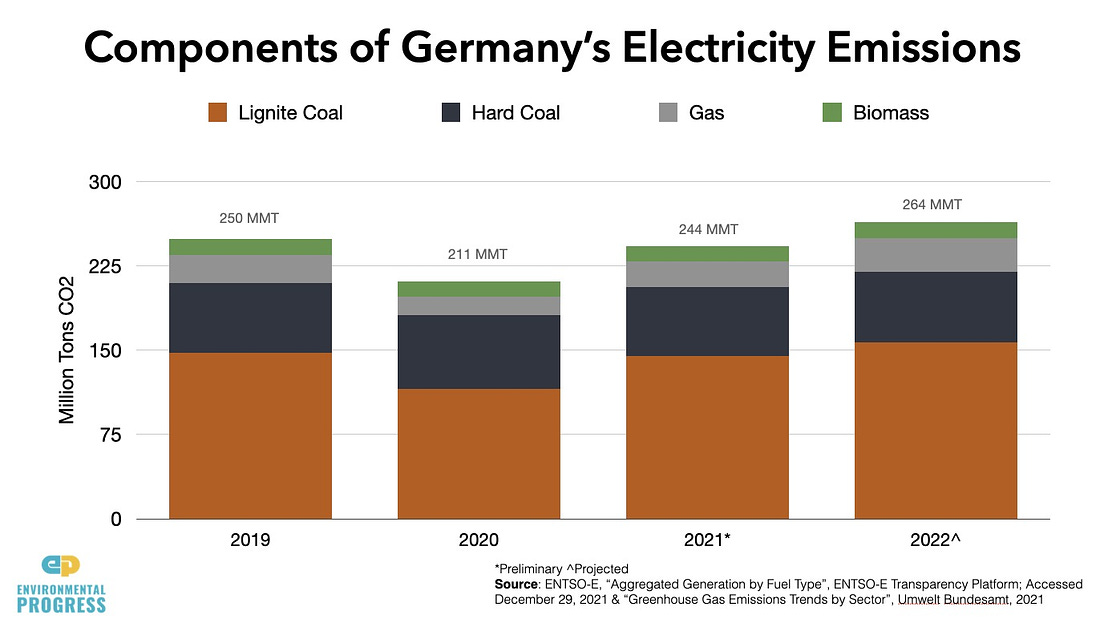

But the EU’s decision to ratify gas and nuclear as green is a major blow to Thunberg and the climate-renewables lobby. It comes on the heels of: the collapse of Biden’s climate agenda in part because it would make the US dangerously dependent on renewables; the hypocrisy of European climate diplomats at United Nations climate talks, demanding Africa remain pure of coal and gas as European energy ministers scrambled to burn coal and acquire natural gas; and, now, Germany’s replacement of half of its nuclear plants with coal and natural gas.

What’s going on? Just a few weeks ago it appeared that Europe was “transitioning to renewables.” Why is it now embracing natural gas and nuclear? And why were Thunberg and the climate movement defeated in Europe, the place where they were presumed to be the strongest? And what does it mean for what happens next?

Michael Shellenberger @ShellenbergerMD

Michael Shellenberger @ShellenbergerMD

October 30th 2021

2,444 Retweets6,438 Likes