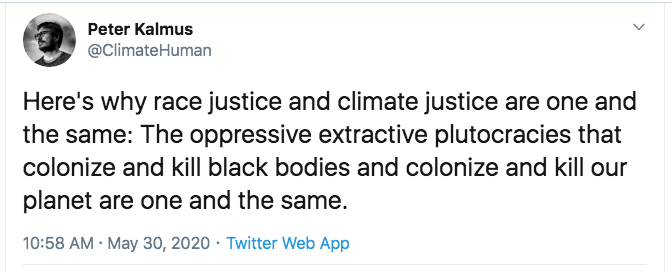

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab climate scientist Peter Kalmus: “Here’s why race justice and climate justice are one & the same: The oppressive extractive plutocracies that colonize and kill black bodies and colonize and kill our planet are one and the same.”

#

January 25, 2021

The Climate Crisis Is Worse Than You Can Imagine. Here’s What Happens If You Try.

Peter Kalmus, out of his mind, stumbled back toward the car. It was all happening. All the stuff he’d been trying to get others to see, and failing to get others to see — it was all here. The day before, when his family started their Labor Day backpacking trip along the oak-lined dry creek bed in Romero Canyon, in the mountains east of Santa Barbara, the temperature had been 105 degrees. Now it was 110 degrees, and under his backpack, his “large mammalian self,” as Peter called his body, was more than just overheating. He was melting down. Everything felt wrong. His brain felt wrong and the planet felt wrong, and everything that lived on the planet felt wrong, off-kilter, in the wrong place.

Nearing the trailhead, Peter’s mind death-spiralled: What’s next summer going to bring? How hot will it be in 10 years? Yes, the data showed that the temperature would only rise per decade by a few tenths of a degree Celsius. But those tenths would add up and the extreme temperatures would rise even faster, and while Peter’s big mammal body could handle 100 degrees, sort of, 110 drove him crazy. That was just not a friendly climate for a human. 110 degrees was hostile, an alien planet.

Lizards fried, right there on the rocks. Elsewhere, songbirds fell out of the sky. There was more human conflict, just as the researchers promised. Not outright violence, not here, not yet. But Peter’s kids were pissed and his wife was pissed and the salience that he’d so desperately wanted others to feel — “salience” being the term of choice in the climate community for the gut-level understanding that climate change isn’t going to be a problem in the future, it is a crisis now — that salience was here. The full catastrophe was here (both in the planetary and the Zorba the Greek sense: “Wife. Children. House. Everything. The full catastrophe”). To cool down, Peter, a climate scientist who studied coral reefs, had stood in a stream for an hour, like a man might stand at a morgue waiting to identify a loved one’s body, irritated by his powerlessness, massively depressed. He found no thrill in the fact that he’d been right.

Sharon Kunde, Peter’s wife, found no thrill in the situation either, though her body felt fine. It was just hot … OK, very hot. Her husband was decompensating. The trip sucked.

“I was losing it,” Peter later recalled as we sat on their front porch on a far-too-warm November afternoon in Altadena, California, just below the San Gabriel Mountains.

“Yeah,” Sharon said.

“Losing my grip.”

“Yeah.”

“Poor Sharon is the closest person to me, and I share everything with her.”

…

Sharon, too, possessed a self-protective mind and heart. A high school English teacher and practiced stoic from her Midwestern German Lutheran childhood, she didn’t believe in saying things you were not yet prepared to act upon. “We find it difficult to understand each other on this topic,” Sharon, 46, said of her husband’s climate fixation.

Yet while Sharon was preternaturally contained, Peter was a yard sale, whole self out in the open. At 47, he worked at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, studying which reefs might survive the longest as the oceans warm. He had more twinkle in his eye that one might expect for a man possessed by planetary demise. But he often held his head in his hands like a 50-pound kettlebell. Every time he heard a plane fly overhead, he muttered, “Fossil fuel noise.”

For years, in articles in Yes! magazine, in op-eds in the Los Angeles Times, in his book “Being the Change: Live Well and Spark a Climate Revolution,” on social media, Peter had been pleading, begging for people to pay attention to the global emergency. “Is this my personal hell?” he tweeted this past fall. “That I have to spend my entire life desperately trying to convince everyone NOT TO DESTROY THE FUCKING EARTH?”

His pain was transfixing, a case study in a fundamental climate riddle: How do you confront the truth of climate change when the very act of letting it in risked toppling your sanity? There is too much grief, too much suffering to bear. So we intellectualize. We rationalize. And too often, without even allowing ourselves to know we’re doing it, we turn away. At virtually every level — personal, political, policy, corporate — we repeat this pattern. We fail, or don’t even try, to rise to the challenge. Yes, there are the behemoth forces of power and money reinforcing the status quo. But even those of us who firmly believe we care very often fail to translate that caring into much action. We make polite, perhaps even impassioned conversation. We say smart climate things in the boardroom or classroom or kitchen or on the campaign trail. And then … there’s a gap, a great nothingness and inertia. What happens if a human — or to be precise, a climate scientist, both privileged and cursed to understand the depth of the problem — lets the full catastrophe in?

Once Peter, Sharon and their 12- and 14-year-old sons set their packs down at the car on that infernal Labor Day weekend, they blasted the air conditioning, then stopped for Gatorade and Flamin’ Hot Doritos to try to recover from their trip. But the heat had descended not just on Peter’s big mammal body but on millions of acres of dry cheatgrass and oak chaparral.

That same afternoon, around 1 p.m., the Bobcat fire started five miles from their house in the Los Angeles hills.

Peter’s climate obsession started, as many obsessions do, with the cross-wiring of exuberance and fear. In late 2005, Sharon got pregnant with their first child, and in the throes of joy and panic that accompanied impending fatherhood, Peter attended the weekly physics colloquium at Columbia University, where he was working on an astrophysics Ph.D. The topic that day was the energy imbalance in the planet — how more energy was coming into earth’s atmosphere from the sun than our atmosphere was radiating back out into space. Peter was rapt. He’d grown up a nerdy Catholic Boy Scout in suburban Chicago, and had always been, as his sister Audrey Kalmus said, someone who “jumped into things he believed in with three feet.” He’d met Sharon at Harvard. They’d moved to New York so she could earn a teaching degree. For a while, before returning to school, Peter had made good money on Wall Street writing code. Now here he was hearing, really hearing for the first time, that the planet, his son’s future home, was going to roast. Full stop.

This was a catastrophe — a physical, physics catastrophe, and here he was, a physicist about to have a son. He exited the lecture hall in a daze. “I was kind of like, ‘Are we just going to pretend this is like a normal scientific talk?’” he told me, recalling his thoughts. “We’re talking about the end of life on Earth as we know it.”

For the next eight months, Peter walked around Manhattan, “freaking out in my brain,” he said, like “one of those end-is-near people with the sandwich boards.” He tried converting Columbia’s undergraduate green groups to his cause. Did they care about the environment? Yes. Did they care about the planetary catastrophe? Well, yes, of course they did, but they were going to stick with their project of getting plastic bags out of dining halls, OK? He tried lobbying the university administrators to switch to wind power. Couldn’t even get a meeting. Nothing made sense. Why was Al Gore spending a fortune to make a climate movie only to flinch at the end of “An Inconvenient Truth” and say, essentially, Just buy more efficient light bulbs? Almost nobody saw it — really saw it. WE ARE HAVING AN EMERGENCY. There was only one possible endgame here if humans didn’t stop burning fossil fuels, fast: global chaos, mass violence, miserable deaths.

Peter and Sharon’s friends came over to meet and bless their baby, Braird, shortly after he was born in June 2006. All the guests went around the room offering wishes for the unborn child. When Peter’s turn came, he said he hoped that his son didn’t get shot at in climate-induced barbarity and that he did not starve.

…

For the family, if Peter quit flying, it meant he’d be home more to help with the kids. Sharon reserved the right to keep flying if she wanted. Win-win.

Peter’s second-largest source of emissions was food. So he started growing artichokes, eggplant, kale and squash, plus tending fruit trees, and that was great. Then he started composting — OK, that’s great, too. He also started keeping bees and raising chickens, and soon raccoons and possums discovered the chickens and Peter began running outside in his underwear in the middle of the night when he heard the chickens scream. Baby chicks lived in the house, which the boys loved. Braird got stung by bees while Sharon was at a meditation retreat and it turned out Braird was allergic and he went into shock.

Next came dumpster diving (which eventually — and thankfully — morphed into an arrangement with Trader Joe’s to pick up their unsellable food every other Sunday night). Peter’s haul — “seven or eight boxes,” according to Sharon; “three boxes,” according to Peter — included dozens of eggs with only one broken. Flats of (mostly not moldy) strawberries. Bread past its sell-by date. Peter did his best to put things away before he fell asleep because waking up to the mess drove Sharon nuts. But … it was a lot. Low-carbon living was a lot.

They stopped using the gas dryer. They stopped shitting in the flush toilet and started practicing “humanure,” composting their own crap. Sharon had lived with an outhouse in Mongolia, “so that was something I was used to,” she said. Plus, to be honest, she liked the local, organic anti-capitalist politics of it. “Marx writes about this in ‘Capital, Volume 1’ that one of the reasons Europeans started to use chemical fertilizers is because people started to move into the cities and off of the land, … and people stopped pooping out in the countryside, so it became less fertile.” The main problem, for Sharon, was that their bathroom was small and the composting toilet was inside. They used eucalyptus leaves to try to cover up the smell, but then little bits of leaves got all over the bathroom, too. After a while Peter moved the composting toilet outdoors. He also built an outdoor shower that Sharon found quite lovely, “rustic and California.”

Sharon commiserated with a friend who was married to a priest. How do you have an equal marriage with a man who’s trying to save the world?

…

WE ARE HAVING AN EMERGENCY — Peter thought that all day, every day. “Here I am with a retirement account,” Peter said. Did he need a retirement account? What was the world going to be like in 2060, when he was an old man? He’d been careful with himself not to become a doomer. Doomers, in his mind, were selfish. They’d given up on the greater good and retreated to their own bunkers, leaving the rest of us to burn. Still, despite Peter’s commitment to keep working toward global change, Sharon found Peter’s florid negativity distasteful at times. “There’s almost like a pornographic fascination with ‘Oh, I’m going to imagine just how bad everything is going to be,’” she said.

…

“WE NEVER EVEN TALK ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE! DO YOU EVEN CARE ABOUT CLIMATE CHANGE?” he said. This did not go well.

She threw a laundry basket. “YOU HAVE GOT TO BE FUCKING KIDDING ME,” she shouted. “Our entire lives are about climate change.”

…

Maeby is now gone. Peter drives an electric car. The composting toilet remains outside, though Peter admits, “The other three family members are not interested in contributing at all.” Peter’s current project is making climate ads. Is this how he can tell the story of what is happening to the world in a way that will make people not just hear and retreat but act? He thinks about this all the time. How do you describe an intolerable problem in a way that listeners — even you, dear reader — will truly let in?

All through October and November, the Bobcat fire continued to burn. It grew to 115,000 acres. Its 300-foot-high flames licked up against Mount Wilson Observatory, where scientists first proved the existence of a universe outside the Milky Way. The fire continued to burn well into December, when UN Secretary-General António Guterres urged, with middling effect, the nations of the world to declare a climate emergency. So far, 38 have done so. The United States is not one of them. In January, a team of 19 climate scientists published a paper, “Underestimating the Challenges of Avoiding a Ghastly Future,” that said, “The scale of the threats to the biosphere and all its life forms — including humanity — is in fact so great that it is difficult to grasp for even well-informed experts.” The language of this sentence could not be more dire. It makes the mind go numb.

So how, with our limited human minds, do we attend enough to make real progress? How do we not flinch and look away? The truth of what is happening shakes the foundations of our sense of self. It asserts a distorting gravity, bending our priorities and warping our whole lives. The overt denialists are easy villains, the monsters who look like monsters. But the rest of us, much of the time, wear pretty green masks over our self-interest and denial, and then go about our days. Then each morning we wake to a new headline like: “The planet is dying faster than we thought.”

While I was trying (and failing) to process it all, Peter called to make sure I understood the importance of a comment he’d made: He’s no longer embarrassed to tell people he would die to keep the planet from overheating. He’s left behind the solace of denial. He’s well aware of the cost. “What a luxury to feel that the ground we walk on and this planet that is rotating around the sun is in some sense OK.”

"His older son thinks there’s no future."

Report from an alarmed climate scientist's family

One would hope that his son also gets to see data on the actual impact — ever fewer people dying from climate-related disasters and lower GDP costshttps://t.co/SCA1GYYL7r pic.twitter.com/jGgKiv7dXy

— Bjorn Lomborg (@BjornLomborg) January 31, 2021