California’s government solely responsible for states forest management and wildfire debacle

by Larry Hamlin

The inept government, political and regulatory policies of California have clearly driven the present forest management calamitous conditions with that failure leading to disastrous wildfires throughout the state.

Those government and political leaders that are responsible for this situation that has been decades in the making have tried to conceal their incompetence by making scientifically unsupported propaganda claims that “climate change” caused this situation. These government driven problems are clearly identified in two recent reports – one by Cal Fire and the other by the California Legislative Analysts Office.

The state has established a huge gauntlet of regulatory agencies whose policies, procedures and actions have interfered with, misdirected, wasted and delayed the use of appropriate resources that have led to the present forest management and wildfire catastrophe.

Cal Fire has identified a series of high priority wildfire policy actions that need to be addressed and that reflect decades long policy inaction by the state which have led to the buildup of increasing wildfire risks that are responsible for the severity of recent California wildfires.

These actions are summarized in the report noted above and include the following assessments:

“Recognizing the need for urgent action, Governor Gavin Newsom issued Executive Order N-05-19 on January 9, 2019. The Executive Order directs the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE), in consultation with other state agencies and departments, to recommend immediate, medium and long-term actions to help prevent destructive wildfires.

With an emphasis on taking necessary actions to protect vulnerable populations, and recognizing a backlog in fuels management work combined with finite resources, the Governor placed an emphasis on pursuing a strategic approach where necessary actions are focused on California’s most vulnerable communities as a prescriptive and deliberative endeavor to realize the greatest returns on reducing risk to life and property.

Using locally developed and vetted fire plans prepared by CAL FIRE Units as a starting point, CAL FIRE identified priority fuel reduction projects that can be implemented almost immediately to protect communities vulnerable to wildfire. It then considered socioeconomic characteristics of the communities that would be protected, including data on poverty levels, residents with disabilities, language barriers, residents over 65 or under five years of age, and households without a car.

In total, CAL FIRE identified 35 priority projects that can be implemented immediately to help reduce public safety risk for over 200 communities. Project examples include removal of hazardous dead trees, vegetation clearing creation of fuel breaks and community defensible spaces, and creation of ingress and egress corridors. These projects can be implemented immediately if recommendations in this report are taken to enable the work. Details on the projects and CAL FIRE’s analysis can be found online which will remain updated in the coming months. The list of projects is attached to this report as Appendix C.

CAL FIRE has also worked with over 40 entities including government and nongovernment stakeholders to identify administrative, regulatory and policy actions that can be taken in the next 12 months to begin systematically addressing community vulnerability and wildfire fuel buildup through rapid deployment of resources. Implementing several of these recommended actions is necessary to execute the priority fuel reduction projects referenced above. Other recommendations are intended to put the state on a path toward long-term community protection, wildfire prevention, and forest health.

The recommendations in this report, while significant, are only part of the solution. Additional efforts around protecting lives and property through home hardening and other measures must be vigorously pursued by government and stakeholders at all levels concurrently with the pursuit of the recommendations in this report. California must adopt an “all of the above” approach to protecting public safety and maintaining the health of our forest ecosystems.

It is important to note that California faces a massive backlog of forest management work. Millions of acres are in need of treatment, and this work— once completed—must be repeated over the years. Also, while fuels treatment such as forest thinning and creation of fire breaks can help reduce fire severity, wind-driven wildfire events that destroy lives and property will very likely still occur.

This report’s recommendations on priority fuel reduction projects and administrative, regulatory, and policy changes can protect our most vulnerable communities in the short term and place California on a trajectory away from increasingly destructive fires and toward more a moderate and manageable fire regime.”

Governor Newsom had to invoke the declaration of a State of Emergency in late March of this year to waive California’s onerous and overbearing environmental laws and regulations to allow for these actions to commence in a timely manner. These most recent actions however represent only very small part of magnitude of the forest management and wildfire problems that must be dealt with by California that will take many years to address.

Another state report completed in 2018 that received little attention by the media documents in much more detail the huge extent of the problems confronting California’s forest management responsibilities.

The California Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) conducted a comprehensive review of the state’s wildfire and forest management situation and presented their results in a report titled “Improving California’s Forest and Watershed Management” which identifies the most critical issues facing the state in these areas including assessing the responsible agencies that need to take a multitude of additional actions.

The study clearly identifies the multiple entities that have ownership responsibility for California’s forestlands including state, federal, local agencies and private parties having numerous regulatory, environmental and administrative responsibilities and authorities relative to California’s forest and the manner in which these agencies share jointly in the responsibilities for addressing actions needed to improve the forest health and watershed management.

The patchwork of Federal, State, local government and private entities which own California’s forest is displayed below in Figure 3 from the LAO report.

The federal government through the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and National Park Service owns about 19 million acres of the total 33 million acres of forestlands in the state of California representing about 57% of the forest areas. Private nonindustrial entities own about one‑quarter (8 million acres) acres of forestland. These include families, individuals, conservation and natural resource organizations, and Native American tribes. Industrial owners—primarily timber companies—own 14 percent (4.5 million acres) of forestland. State and local governments own about a 3 percent (1 million acres) combined. In total these non-federal entities represent about 43% of the states forest areas.

Increased fire risks are present throughout the state driven by forest conditions that have been allowed to develop for years. The report notes that:

“Dense forest stands that are proliferated with small trees and shrubs contain masses of combustible fuel within close proximity, and therefore can facilitate the spread of wildfires. Moreover, these smaller trees can serve as “ladder fuels” that carry wildfire up into the crowns of taller trees that might have otherwise been out of reach, adding to a fire’s potential spread and intensity. As shown in Figure 11, Cal Fire estimates that most forested regions of the state face a high to extreme threat of wildfires. Cal Fire estimates the level of threat based on a combination of anticipated likelihood and severity of a fire occurring.”

“In addition to increasing fire risk, overcrowded forests and the associated competition for resources can also make forests less resilient to withstanding other stressors. For example, trees in dense stands become more vulnerable to disease—including infestations of pests such as bark beetles—and less able to endure water shortages from drought conditions. This vulnerability has been on display in recent years, as an estimated 129 million trees in California’s forests died between 2010 and 2017, including over 62 million dying in 2016 alone. While this is a relatively small share of the over 4 billion trees in the state, historically, about 1 million of California’s trees would die in a typical year. Moreover, most of the die‑off is occurring in concentrated areas. For example, the Sierra National Forest has lost nearly 32 million trees, representing an overall mortality rate of between 55 percent and 60 percent. When dead trees fall to the ground they add more dry combustible fuel for fires, as well as pose risks to public safety when they fall onto buildings, roads, and power lines.”

Specifically identified in the report is an extremely important requirement often ignored by those trying to assign or deny responsibility for California’s forest management problems on the basis of who owns these lands. This requirement stipulates that regardless of ownership of the numerous forest properties the following key provisions apply:

“While forest management responsibilities typically align with ownership, natural processes—such as forest fires, water runoff, and wildlife habitats—do not observe those jurisdictional boundaries. As such, federal and state agencies have developed certain arrangements to collaborate on management activities across California’s forests. For example, federal law has a provision—known as the “Good Neighbor Authority”—that allows states to fund and implement forest health projects on federally owned land. As discussed later, the federal government also funds a number of grant programs to encourage collaborative projects on both federal and nonfederal forestlands. Additionally, federal and state agencies have established agreements for collaborative fire suppression efforts across jurisdictions when fires do occur.”

Both the state and federal government exercise extensive government and regulatory control over California forestland activities through numerous organizations as noted in Figure 6 from the report.

Additionally, the state of California has a large number of regulatory agencies whose procedures and processes have significant impacts on the ability of actions to go forward in a timely and effective manner regarding necessary forest management efforts. These numerous agencies are defined in Figure 7 below.

Also addressed in the LAO analysis is a discussion of the huge backlog of forest lands requiring actions to restore forest health and decrease wildfire risks including 20 million acres on state regulated lands and 9 million acres of federally regulated lands noted as follows:

“The draft Forest Carbon Plan states that 20 million acres of forestland in California face high wildfire threat and may benefit from fuels reduction treatment. According to the plan, Cal Fire estimates that to address identified forest health and resiliency needs on nonfederal lands, the rate of treatment would need to be increased from the recent average of 17,500 acres per year to approximately 500,000 acres per year. The plan does not include associated cost estimates.”

“Based on its ecological restoration implementation plan, USFS estimates that 9 million acres of national forest system lands in California would benefit from treatment. The draft Forest Carbon Plan sets a 2020 goal of increasing the pace of treatments on USFS lands from the current average of 250,000 acres to 500,000 acres annually, and on BLM lands from 9,000 acres to between 10,000 and 15,000 acres annually.”

The report provides a definition of what functions, duties and responsibilities are associated with performing forest management actions as follows:

“Forest management” is generally defined as the process of planning and implementing practices for the stewardship and use of forests to meet specific environmental, economic, social, and cultural objectives. Activities forest managers employ include timber harvesting (typically for commercial purposes), vegetation thinning (clearing out small trees and brush, often through mechanical means or prescribed burns), and reforestation (planting new trees). Figure 5 describes specific activities that managers typically undertake to improve the health of forests. As discussed later, research has shown that these are the types of activities that are most effective at preserving and restoring the natural functions and processes of forests, and thereby maximizing the natural benefits that they can provide. Efforts to extinguish active wildfires are not generally considered to be forest management activities, as they are more responsive than proactive.”

The very poor forest conditions that exist today are a consequence of decades of inappropriate forest management neglect and are described as follows:

“As noted above, forest management practices and policies over the past several decades have (1) imposed limitations on timber harvesting, (2) emphasized fire suppression, and (3) instituted a number of environmental permitting requirements. These practices and policies have combined to constrain the amount of trees and other growth removed from the forest. This has significantly increased the density of trees in forests across the state, and particularly the prevalence of smaller trees and brush. Overall tree density in the state’s forested regions increased by30 percent between the 1930s and the 2000s.

These changes have also contributed to changing the relative composition of trees within the forest such that they now have considerably more small trees and comparatively fewer large trees. Figure 10 illustrates some key differences between healthy and overly dense forests. The increase in tree density can have a number of concerning implications for California’s forests—including increased mortality caused by severe wildfires and disease—as displayed in the figure and discussed below.”

The very important function of timber harvesting on both state and federal regulated forests has been particularly hard hit and is described in the LAO report as follows:

“Figure 4 shows the amount of timber harvested in California on both private and public lands over the past 60 years. While subject to annual variation, total timber harvesting in California has declined by over two‑thirds since the late 1950s. As shown in the figure, harvest rates have dropped from over 4.8 billion board feet in1988—its recent peak—to about 900 million in 2009, when it was at its lowest in recent history—a decline of over 80 percent.”

“These trends are due to a variety of factors, including changes in state and federal timber harvesting policies. For example, several federal laws were passed in the 1970s that shifted the USFS’s forest management objectives away from production forestry and more toward conservation and ecosystem management. Those laws included the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)—which requires federal agencies to evaluate any actions that could have a significant effect on the environment—and the Endangered Species Act—which prohibits federal agencies from carrying out actions that might adversely affect a species listed as threatened or endangered. Environmental protection policies have also contributed to declines in private harvests, along with other factors. More recently, the economic recession in the late 2000s sharply reduced demand for new housing construction, thereby also suppressing demand for timber. Since 2009, timber harvesting rates have picked up somewhat, but have not returned to earlier levels.”

There are a significant number of state polices and practices which have exacerbated the ability to proceed with needed timber harvests noted as follows:

“We find that one key component of the state’s FPR (Forest Practice Rules) —that a THP (Timber Management Plan) or other timber management plan generally must be prepared any time timber is removed from the forest and sold commercially—may be inhibiting some beneficial forest restoration work. Restoration and forest management work often involves the removal of trees that could be commercially viable. When sold, the revenue generated from sales can help offset the cost of restoration activities.

However, selling any forest products commercially usually requires additional documentation, such as a THP. The FPR were initially created to regulate timber harvesting on private lands in order to ensure that logging was done in a sustainable manner. At the time, the Legislature was concerned that forests were being overharvested for commercial purposes. This led to the requirement that a THP be prepared anytime harvested trees are to be sold. However, based on our conversations with stakeholders, small landowners and proponents of forest restoration projects are finding that the costs and time associated with preparing one of these plans can be cost prohibitive. They therefore often forego preparing such plans, meaning they also forego the opportunity to earn revenues from selling any marketable timber. Foregoing that revenue reduces the total number of projects that can be undertaken with limited resources.

Solutions to address this concern have been attempted—most notably, the implementation of NTMP (Non-Industrial Timber Management Plan) and the more recent Working Forest Management Plan program, which have fewer planning requirements for smaller landowners and are valid for a longer time period compared to THPs. While these strategies reduce regulatory costs for landowners compared to preparing THPs, they still present substantial upfront costs that are problematic for some small landowners.”

The multitude of state agencies and regulators involved with reviews and approval authority have significantly inhibited needed forest management health activities as identified in the report as follows:

“While the multiple state permits required to carry out many forest health activities (described in Figure 7 on page 12) are intended to protect against undue negative environmental impacts, these requirements are likely inhibiting some of the potential positive environmental effects that improved forest health could yield. (Our findings and recommendations focus on state regulatory requirements, since federal laws and permits are beyond the scope of the state Legislature’s authority to change.)

Project proponents seeking to conduct activities to improve the health of California’s forests indicate that in some cases, state regulatory requirements can be excessively duplicative, lengthy, and costly, thereby delaying and limiting the pace and scale of their proposed projects. In particular, stakeholders suggest that undertaking large‑scale, multiphase treatments across many acres of forest land—referred to as “landscape‑level” projects—can be particularly difficult given existing permitting structures. This is because regulatory agencies often consider each phase of the work as a specific project needing an individual set of costly and time‑intensive permits, rather than considering and approving the overall strategy.

Additionally, when entities want to use state funds to conduct a thinning project on federal forestlands, in certain cases they must conduct both the federally required NEPA review and certain components of the state required CEQA review, and undertake multiple public comment and scoping periods. As we discussed earlier, while certain permit exemptions and streamlined processes do exist—such as specific programmatic EIRs—these only apply for certain types of projects.”

The state agencies reviews of needed prescribed fire burn projects delay or encumber the ability to utilize this needed process noted in the report as follows:

“Several Limitations Constrain Use of Prescribed Fire. There are three main conditions that must be met in order for a prescribed burn to take place under VMP (Vegetation Management Program). First, all documentation—including a burn plan, CEQA compliance, and air quality permits—must be completed by the landowner and Cal Fire for the project in advance. Second, Cal Fire firefighters must be available in the same geographical area as the project in order to conduct the burn. Third, weather conditions and other factors—such as wind speed, humidity, temperature, and air quality—must be within specified limits established in the burn plan and air quality permit.”

We found in different situations any of these three conditions can impede the ability of a VMP project to proceed. In some cases, weather conditions are such that a prescribed burn might affect air quality conditions in a nearby community in violation of the air quality permit. In other situations, Cal Fire fire crews are not available to conduct prescribed burns because they are engaged in firefighting activities. We note that in recent years, the Legislature has provided Cal Fire with additional year‑round firefighting staff, which should increase the department’s capacity both to combat wildfires and conduct prescribed burns and other proactive forest management activities.”

“As discussed earlier, biomass that is not utilized is most frequently disposed of by open pile burning. While this approach is often less expensive than efforts to use biomass, it still requires landowners to invest significant time, planning, and funding. These challenges can also create barriers for undertaking forest thinning projects. Typically, open pile burns require air quality permits from local air districts, burn permits from local fire agencies, and potentially other permits depending on the location, size, and type of burn. To reduce smoke, permits restrict the size of burn piles and vegetation that can be burned, the hours available for burns, and the allowable moisture levels in the material.

These restrictions limit the amount of biomass that can be disposed of and increase the per‑unit disposal costs. While the Regulations Working Group of the Tree Mortality Task Force recently issued new guidelines—under the authority of the Governor’s tree mortality‑related executive order—for high hazard zone tree removal that relaxed some of those permit requirements, these exceptions only apply in areas of extreme tree mortality. For example, the guidelines allow more burning to take place under different weather conditions, such as slightly higher wind or temperature conditions.”

State energy and environmental polices have decreased the ability to deal with disposing of the significant amount of biomass material which is created when needed forest thinning is undertaken. This result has made it more difficult and expensive to undertake needed forest thinning. The report summaries this issue as follows:

“Some stakeholders report that costs associated with the limited options for utilizing or disposing of woody biomass can prohibit them from undertaking projects that would improve the health of their forestlands, or limit the amount of acres they are able to thin. As discussed earlier, woody biomass typically is not useable in traditional lumber mills. This is because these byproducts of timber harvest or thinning operations may be of an undesirable species, too small in diameter for lumber production, or malformed.

Historically, much of this excess forest product was burned to produce bioenergy. However, a significant number of bioenergy facilities have closed over the course of the past two decades. Specifically, in 1991, there were 54 woody biomass processing facilities across the state, with the capacity to produce around 760 megawatts of electricity. In contrast, at the end of 2017 there were only 22 operational facilities with a total capacity of 525 megawatts. These closures have occurred as facilities—largely built in the 1980s—fell out of compliance with more modern air and energy standards, and as bioenergy has increasingly had to compete with cheaper energy sources such as wind, solar, and natural gas.”

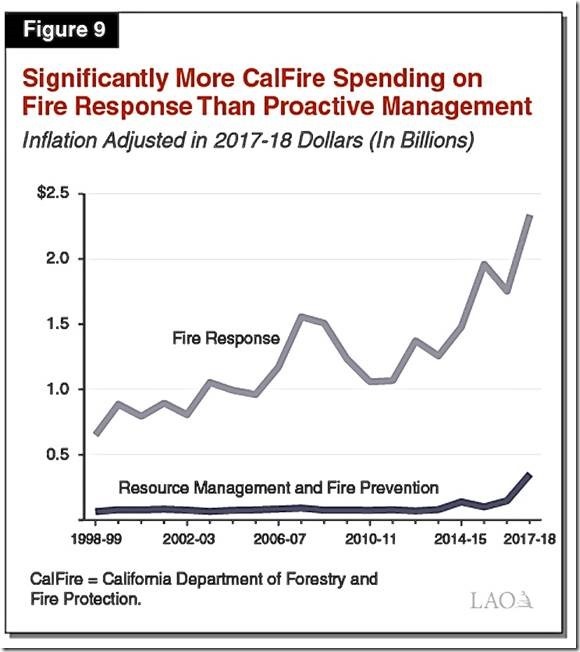

The state has improperly focused priority on fire fighting instead of fire prevention that is achieved through effective forest management actions as shown in Figure 9 from the report. This is resulting in the ineffective and costly misallocation of billions of dollars that are driving the continuation of unhealthy forests and increasing wild fire risks and occurrences.

The federal government changed its priority in 1964 from fire control to fire management as noted in the report:

“The passage of the 1964 Wilderness Act encouraged allowing natural processes to occur, including fire. Accordingly, USFS has changed its policy from fire control to fire management, allowing fires to play their natural ecological roles as long as they can be contained safely based on weather patterns, terrain, proximity to development, and other factors. This policy includes both naturally caused fires and intentionally prescribed fires. This shift reflects a growing resurgence in the perspective that moderate fires can have beneficial effects on forestlands, such as clearing out smaller brush and stimulating natural processes like tree seed dispersal and replenishment of soil nutrients.”

California’s government and regulatory agency policies, procedures and actions are out of step with the need to address forest management actions in a manner that effectively enhances forest health and decrease wildfire risks and occurrences.

The LAO report issues noted above do not represent all of the problem areas identified in this report but provide a clear portrayal of the staggering and mind numbing complexity and ineffectiveness of the states governmental and regulatory agencies and policies that have led to the present debacle in California forest management with the result being significantly increased wildfire risks and occurrences with devastating results in California’s communities.

Those responsible for this dire situation in the state government and its regulatory agencies along with their media supporters have tried to conceal the state’s role in manufacturing this debacle and instead falsely focus attention on scientifically unsupported claims of “climate change” as being responsible for California’s problems while Californians continue to suffer.

In addition to the states massive overlay of ineffective and bureaucratic regulatory agencies that have made such a mess of dealing with California’s forest management and wildfire prevention needs a new impediment from these agencies has now emerged regarding the critical ability for communities experiencing disastrous wild fires such as occurred in the city of Paradise to be able to proceed with recovery as noted in a recent Sacramento Bee article.

The article notes:

“Environmental concerns, including fear of harming sensitive frog species, have forced Camp Fire crews to back away from cleaning some properties in the Paradise area.

State officials tasked with debris cleanup say they have been directed not to enter an estimated 800 burned Butte County home sites within 100 feet of a waterway. They’ve been told to wait for representatives of several state and federal agencies to reach an agreement on environmental assessment guidelines.

The issue cropped up well into a yearlong, estimated $2 billion-plus cleanup operation at about 11,000 properties in Paradise, Concow, and Magalia that burned in November’s Camp Fire, the most destructive blaze in state history.

The revelation that some stream-side properties are now on hold triggered a strong public rebuke Thursday from two local legislators who said they heard about the issue from angry constituents on the ridge.”

The state’s climate alarmist politicians, media and climate activists have attempted to make nebulous and lame excuses that man made “climate change” is accountable for the poor forest conditions and increased wildfires but these claims are unsupported by climate data going back more than 1,000 years showing extensive periods of extreme droughts and precipitation in California have long existed and that no definitive change in this very long term climate record has been established as was noted in a Los Angeles Times article from 2014.

In a more recent Los Angeles Times article the headline speculated that man made climate change impacts maybe associated with the long record of the states drought and precipitation on the basis of “computer models” but the articles substance doesn’t support the hype reflected in its headline. In fact the article states that:

“Some researchers aren’t yet convinced that the results show a clear human influence on past drought trends.”

“But scientists have had a tougher time picking out the effects on precipitation, which should increase in some places and decrease in others.”

“Part of the problem is that the changes driven by humanity’s production of greenhouse gases usually get swamped by the tremendous natural variability of the climate system, particularly when studying the history of a specific region.”

“Other researchers said the study authors’ method can’t determine whether the soil moisture changes recorded in the tree ring data occurred because of an increase in greenhouse gases or because of natural causes — which are also included in the model simulations used to create the fingerprint. For instance, there’s evidence that the sun emitted slightly more energy over the first half of the 20th century, which also affected the climate.”

An extensive study published in ScienceDirect addressed the North American drought history going back to year 800 using tree ring data. The study noted the following regarding the long term climate behavior of drought and precipitation in the West:

“Severe drought is the greatest recurring natural disaster to strike North America. A remarkable network of centuries-long annual tree-ring chronologies has now allowed for the reconstruction of past drought over North America covering the past 1000 or more years in most regions. These reconstructions reveal the occurrence of past “megadroughts” of unprecedented severity and duration, ones that have never been experienced by modern societies in North America. There is strong archaeological evidence for the destabilizing influence of these past droughts on advanced agricultural societies, examples that should resonate today given the increasing vulnerability of modern water-based systems to relatively short-term droughts.”

“Recent advances in the reconstruction of past drought over North America and in modeling the causes of droughts there have provided important new insights into one of the most costly recurring natural disasters to strike North America. A grid of summer PDSI reconstructions has been developed now for most of North America from a remarkable network of long, drought sensitive tree-ring chronologies. These reconstructions, many of which cover the past 1000 yr, have revealed the occurrence of a number of unprecedented megadroughts over the past millennium that clearly exceed any found in the instrumental records since about AD 1850, including an epoch of significantly elevated aridity that persisted for almost 400 yr over the AD 900–1300 period. In terms of duration, these past megadroughts dwarf the famous droughts of the 20th century, such as the Dust Bowl drought of the 1930s, the southern Great Plains drought of the 1950s, and the current one in the West that began in 1999 and still lingers on as of this writing in 2005.”

These results established natural climate drivers are behind the extensive drought and precipitation cycles over the last more than 1,000 years as noted in the graph provided below indicating that the politically driven claims by climate alarmists that “climate change” is driving drought and precipitation outcomes in the West is flawed.

The 1,000 year long tree ring data record provided in the information above demonstrates that California has been subjected to extensive intervals of natural climate change driven cycles of droughts and precipitation events for centuries. Claims that recent drought and precipitation events are somehow influenced by “man made climate change” are scientifically flawed and represent nothing but climate alarmist speculation and conjecture.

The Cal Fire and LAO reports present a real world picture identifying that California’s government and regulatory agencies are responsible for the present terrible condition of California’s forests along with the resulting increased wildfire risks and occurrences. The excuse that “climate change” has caused these problems is nothing but scientifically unsupported propaganda being used in an attempt to conceal that the state government is really responsible for these outcomes.