Image source: 2 November 2018 Washington Post

By Kenneth Richard

According to climatologist Dr. Michael Mann, we human beings are significantly modulating the globe’s hydrological cycle by warming the planet.

Mann postulates that anthropogenic global warming (AGW) causes the wet regions of the Earth to get wetter, whereas the dry regions of the Earth get drier (“DDWW” in the scientific literature). In other words, AGW causes extreme weather patterns to worsen, or occur with greater frequency and intensity.

Mann even finesses his readers by characterizing the link between AGW and extreme weather as so obvious and facile a layperson can understand it. This is ostensibly what the epigram “It’s not rocket science” is designed to convey.

Real-world observations contradict Mann’s claims

Dr. Mann claims that “it’s not rocket science” that global warming has led to “unprecedented” extremes in droughts (too little precipitation) and floods (too much precipitation). He insists that we must take “concerted action” to mitigate our use of fossil fuels so as to avert these “disastrous” and “devastating” extreme weather consequences.

Mann classifies those who disagree with him about the link between AGW and these extreme weather events as “climate deniers”.

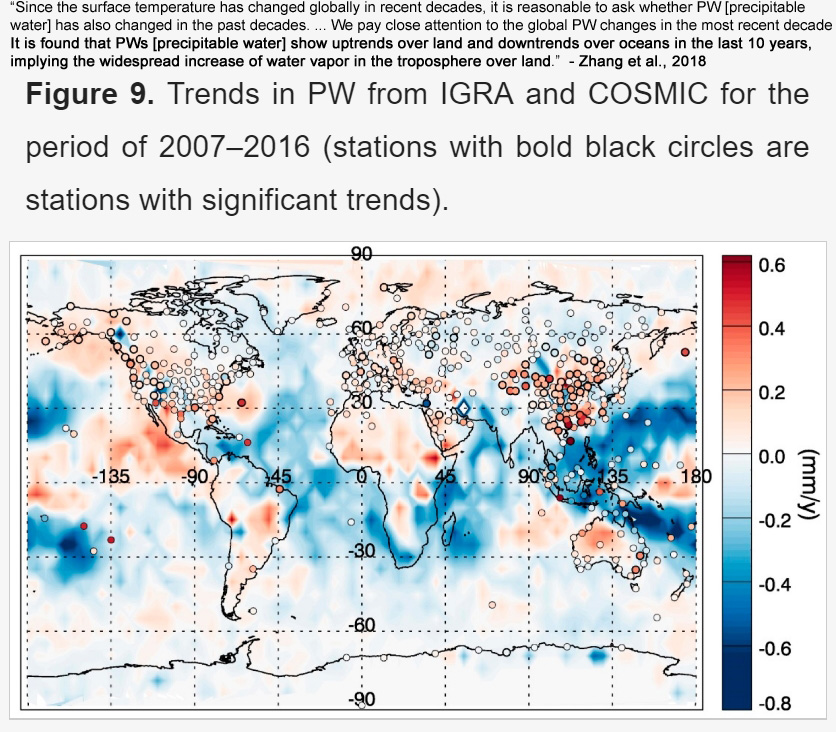

Despite the certainty in the “rightness” of his claims, the real-world satellite observations of precipitable water and precipitation changes during the last few decades do not confirm the narrative of an intensifying hydrological cycle in response to global warming.

For example, Mann claims that “a warmer ocean evaporates more moisture into the atmosphere”. But recent observational evidence indicates that precipitable water has been declining over the global oceans for the last decade – the opposite of what Mann claims is happening.

• “According to the global observations, it is found that PWs [percipitable water] show uptrends over land and downtrends over the ocean in last 10 years [2007-2016], implying the widespread increase of water vapor in the troposphere over land.” (Zhang et al., 2018)

Image Source: Zhang et al., 2018

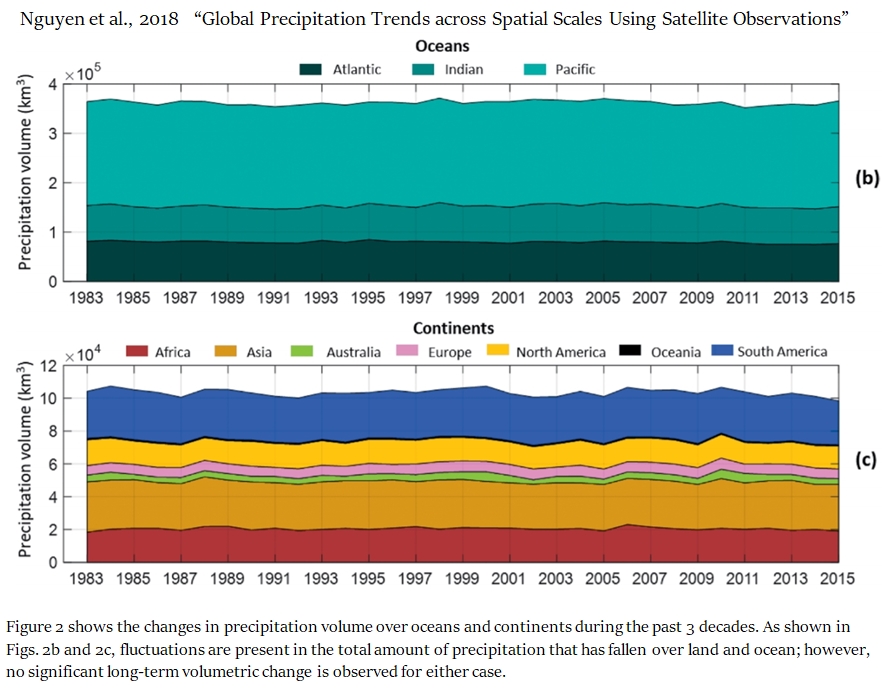

Comprehensive analyses further reveal no detectable changes in the Earth’s precipitation patterns in recent decades, as a dry gets wetter and wet gets drier trend is about as likely to occur as a wet gets wetter and dry gets drier(DDWW) one.

• “Here we present an analysis of more than 300 combinations of various hydrological data sets of historical land dryness changes covering the period from 1948 to 2005. Each combination of data sets is benchmarked against an empirical relationship between evaporation, precipitation and aridity. Those combinations that perform well are used for trend analysis. We find that over about three-quarters of the global land area, robust dryness changes cannot be detected. … Only 10.8% of the global land area shows a robust ‘dry gets drier, wet gets wetter’ pattern, compared to 9.5% of global land area with the opposite pattern, that is, dry gets wetter, and wet gets drier. We conclude that aridity changes over land, where the potential for direct socio-economic consequences is highest, have not followed a simple intensification of existing patterns.” (Greve et al., 2014)

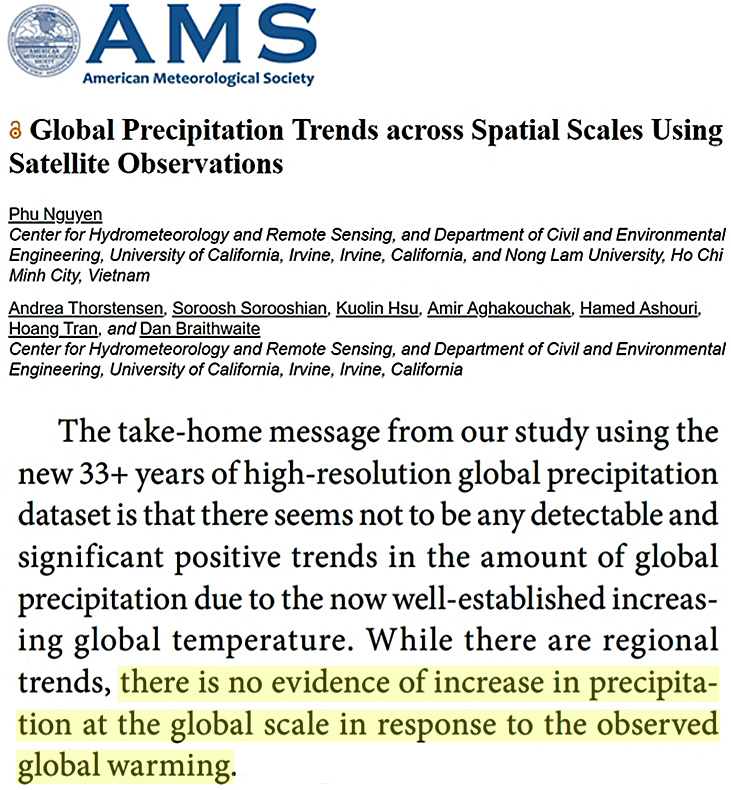

• “The take-home message from our study using the new 33+ years [1983-2015] of high-resolution global precipitation dataset is that there seems not to be any detectable and significant positive trends in the amount of global precipitation due to the now well-established increasing global temperature. While there are regional trends, there is no evidence of increase in precipitation at the global scale in response to the observed global warming.” (Nguyen et al., 2018)

Image Source: Nguyen et al., 2018

• “In the current study, trends in major-flood occurrence from 1961 to 2010 and from 1931 to 2010 were assessed using a very large dataset (>1200 gauges) of diverse catchments from North America and Europe … Overall, the number of significant trends in major-flood occurrence across North America and Europe was approximately the number expected due to chance alone. Changes over time in the occurrence of major floods were dominated by multidecadal variability rather than by long-term trends. There were more than three times as many significant relationships between major-flood occurrence and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation than significant long-term trends. … The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded (Hartmann et al., 2013) that globally there is no clear and widespread evidence of changes in flood magnitude or frequency in observed flood records. … North American trends in … frequency of extremes in the 1980s and 1990s were similar to those of the late 1800s and early 1900s. There was no discernible trend in the frequency of extreme events in Canada. The results of this study, for North America and Europe, provide a firmer foundation and support the conclusion of the IPCC (Hartmann et al., 2013) that compelling evidence for increased flooding at a global scale is lacking.” (Hodgkins et al., 2017)

• “The main objective of this paper is to detect the evidence of statistically significant flood trends across Europe using a high spatial resolution dataset. … Anticipated changes in flood frequency and magnitude due to enhanced greenhouse forcing are not generally evident at this time over large portions of the United States for several different measures of flood flows. … Thus, similarly to the main findings of Archfield et al. (2016) for the US, the picture of flood change in Europe is strongly heterogeneous and no general statements about uniform trends across the entire continent can be made.” (Mangini et al., 2018)

• “In this study, a monthly water-balance model is used to simulate monthly runoff for 2109 hydrologic units (HUs) in the conterminous United States (CONUS) for water-years 1901 through 2014. … Results indicated that … the variability of precipitation appears to have been the principal climatic factor determining drought, and for most of the CONUS, drought frequency appears to have decreased during the 1901 through 2014 period.” (McCabe et al., 2017)

• “For the extreme drought and flood events in total, more frequent of them occurred in the 1770s and 1790s, 1870s–1880s, 1900s–1920s and 1960s, among which the 1790s witnessed the highest frequency of extreme drought and flood events totally.” (Zheng et al., 2018)

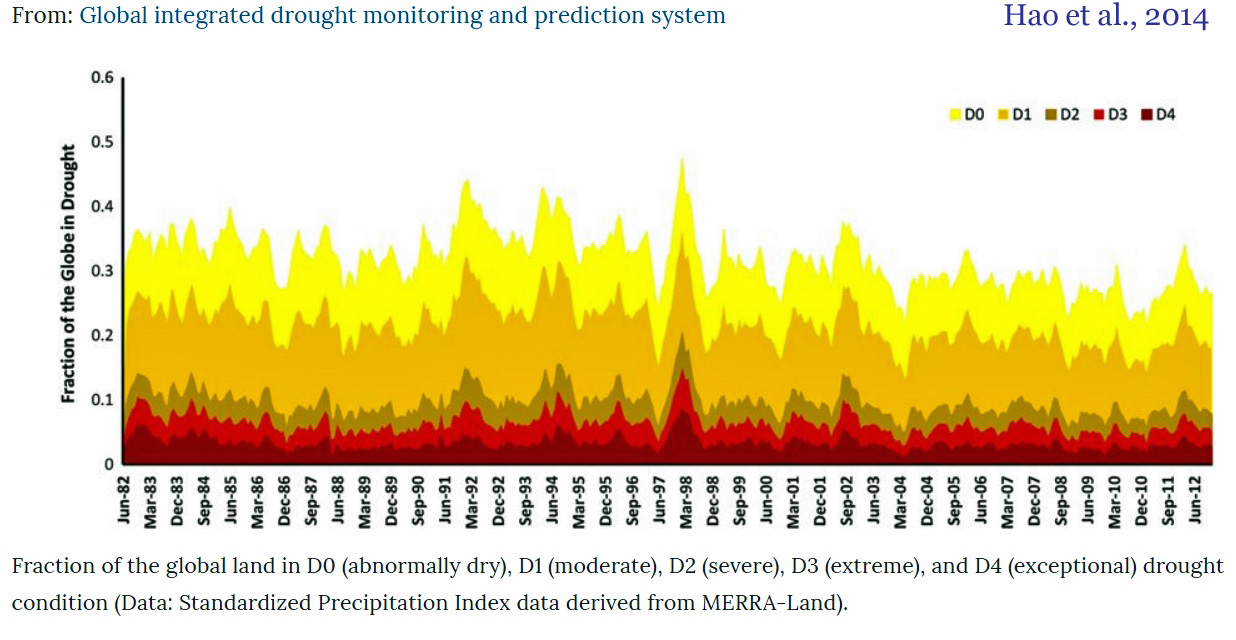

• “GIDMaPS climate data records can be used to assess the fraction of global land areas under D0 to D4 drought severity levels” (Hao et al., 2014)

Image Source: Hao et al., 2014

Mann believes AGW leads to more frequent and intensified heat waves

Mann maintains AGW has increased the likelihood that deadly and “unprecedented” heat waves will occur. In the Washington Post article, he points out that 30,000 people died in the 2003 European heat wave, and that we can expect more of the same in the near future unless we “act”.

However, just as with the precipitation patterns, the real-world observations do not support these claims.

Scientists have concluded that heat waves are driven by natural variability (Dole et al., 2011, Shiogama et al., 2013, Dole and Hoerling, 2014).

Furthermore, there have been no detectable long-term trends in increased heat waves during the last several decades.

• “For the conterminous United States, the highest number of heat waves occurred in the 1930s, with the fewest in the 1960s. The 2001–10 decade was the second highest but well below the 1930s. Regionally, the western regions (including Alaska) had their highest number of heat waves in the 2000s, while the 1930s were dominant in the rest of the country.” (Peterson et al., 2013 )

• “Heat waves are primarily driven by internal atmospheric variability (Schubert et al. 2011, Dole et al. 2011), but their frequency of occurrence and severity can be modulated by atmospheric boundary forcing. Soil moisture deficits have been shown to play an important role in intensifying heat wave severity (Huang and Van den Dool 1993, Fischer et al. 2007, Jia et al. 2016, Donat et al. 2016). … Low frequency SST variations may explain why there has not been any long-term trend of heat waves detected over the US during the 20th century, despite the increase of radiative forcing (Kunkel et al. 1999, Easterling et al. 2000).” (Ruprich-Robert et al., 2018)

Image Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

More people are dying from cold weather extremes – heat-related deaths are decreasing

Considering there is apparently an obvious, “it’s-not-rocket-science” link between AGW and increased heat wave frequency and intensity, there should be a concomitant uptick in both heat-related deaths and a decline in cold weather-related mortality.

Real-world observations indicate the opposite has occurred in the last several decades: cold weather deaths have been stable to increasing, whereasheat-related deaths have been declining throughout the world.

• “We demonstrate that cold temperatures contributed to higher attributable risks of mortality than hot temperatures in India during 2001–2013, consistent with previous findings based on nonlinear temperature–mortality associations drawn from mostly high-income countries. These previous findings reported an overall attributable risk of 7.29% (eCI 7.02 to 7.49) for cold temperature and 0.42% (0.39 to 0.44) for hot temperature, which are similar to our results for all ages. Among countries, our results are most comparable to those of Australia.” (Fu et al., 2018)

• “Cold temperatures exhibit larger attributable mortality (above 5%) compared to heat (around or below 1%) in all countries. Cold-mortality impacts persisted throughout the study periods in most of the countries, although following different temporal patterns. Canada, Japan, Spain, Switzerland, South Korea and the USA show a decreasing trend in heat-attributable AFs, from 0.45–1.66% in the first 5-year sub-period to 0.15–0.93% in the last 5-year sub-period. Heat impacts remained stable in UK and Brazil at around 0.2–0.4% and 0.6–0.7%, respectively, whereas it increased in Australia from 0.05% to 0.67%.” (Vicedo-Cabrera et al., 2018)

• “Projections of temperature-related mortality rely upon exposure-response relationships using recent data. Analyzing long historical data and trends may extend knowledge of past and present impacts that may provide additional insight and improve future scenarios. We collected daily mean temperatures and daily all-cause mortality for the period 1901–2013 for Stockholm County, Sweden, and calculated the total attributable fraction of mortality due to non-optimal temperatures and quantified the contribution of cold and heat. Total mortality attributable to non-optimal temperatures varied between periods and cold consistently had a larger impact on mortality than heat. Cold-related attributable fraction (AF) remained stable over time whereas heat-related AF decreased.” (Oudin Åström et al., 2018)

• “This study investigated the change in risks of mortality from heat waves and cold spells over time, and estimated the temporal changes in mortality burden attributed to heat waves and cold spells in Korea and Japan. We collected time-series data covering mortality and weather variables from 53 communities in the two countries from 1992 to 2015. Two-stage time-series regression with a time-varying distributed lag model and meta-analysis was used to assess the impacts of heat waves and cold spells by period (1990s, 2000s, and 2010s). In total population, the risks of heat waves have decreased over time; however their mortality burden increased in the 2010s compared to the 2000s with increasing frequency. On the other hand, the risk and health burden of cold spells have increased over the decades.” (Lee et al., 2018)

• “We investigated the lag structure of the mortality response to cold and warm temperatures in 18 French cities between 2000 and 2010. … The fraction of mortality attributable to cold and heat was estimated with reference to the minimum mortality temperature. … Results: Between 2000 and 2010, 3.9% [CI 95% 3.2:4.6] of the total mortality was attributed to cold, and 1.2% [1.1:1.2] to heat.” (Pascal et al., 2018)

• “We conducted a time-series analysis using daily temperature data and a national dataset of all 8.8 million recorded deaths in South Africa between 1997 and 2013. Mortality and temperature data were linked at the district municipality level and relationships were estimated with a distributed lag non-linear model with 21 days of lag, and pooled in a multivariate meta-analysis. We found an association between daily maximum temperature and mortality. Total attributable mortality was 3.4%, mostly from cold (3.0%) rather than heat (0.4%).” (Scovronick et al., 2018)

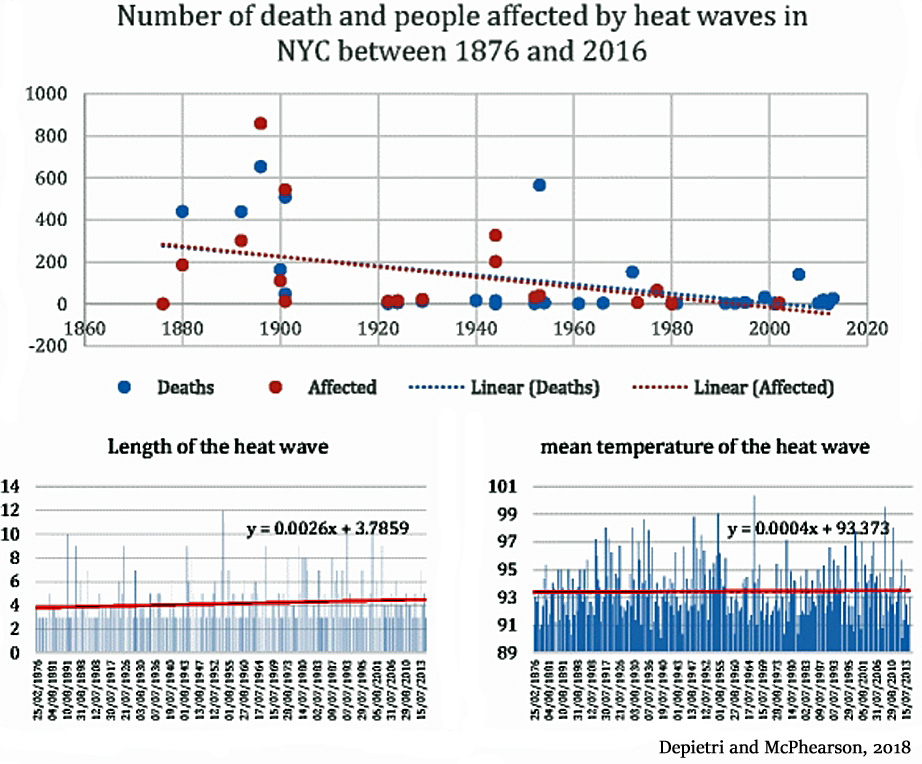

• “The trends based on the NOAA meteorological data show that changes in the length of the heat wave events equal or beyond 3 days of duration are not significant. The mean maximum temperature of the heat wave is also close to stable over the 140-year period of study with no significant increase. … Results obtained from the in-depth analysis of the NYT articles, corresponding to the dates of longer lasting heat wave events (i.e., equal or more than 6 days in duration), show that the number of deaths and people affected in New York City significantly declined. … The change in coping strategies mentioned in the newspapers articles and divided before and after the 1960s illustrates how the advent of air conditioning can be most likely contributed to the significant reduction in mortality due to extreme heat. … Also not significant are the trends in extreme precipitation (beyond 1.75 in. and beyond 3.5 in.) with significant inter-annual and interdecadal variability.” (Depietri and McPhearson, 2018)

Images Source: Depietri and McPhearson, 2018

Mann claims AGW has caused an increase in global fire frequency

The it’s-not-rocket-science link between anthropogenic global warming and the frequency of wildfires is also not supported by real-world observational data.

Globally, there has been a significant decline in fire frequency during the last several decades, and wildfires have been less common in the last century than “at any time in the past 2000 years“.

• “Wildfire has been an important process affecting the Earth’s surface and atmosphere for over 350 million years and human societies have coexisted with fire since their emergence. Yet many consider wildfire as an accelerating problem, with widely held perceptions both in the media and scientific papers of increasing fire occurrence, severity and resulting losses. … However, important exceptions aside, the quantitative evidence available does not support these perceived overall trends. Instead, global area burned appears to have overall declined over past decades, and there is increasing evidence that there is less fire in the global landscape today than centuries ago. … Analysis of charcoal records in sediments [Marlon et al., 2008] and isotope-ratio records in ice cores [Wang et al., 2010] suggest that global biomass burning during the past century has been lower than at any time in the past 2000 years.” (Doerr and Santín, 2016)

• “We find that there is a strong statistically significant decline in 2001–2016 active fires globally linked to an increase in net primary productivity observed in northern Africa, along with global agricultural expansion and intensification, which generally reduces fire activity.” (Earl and Simmonds, 2018)

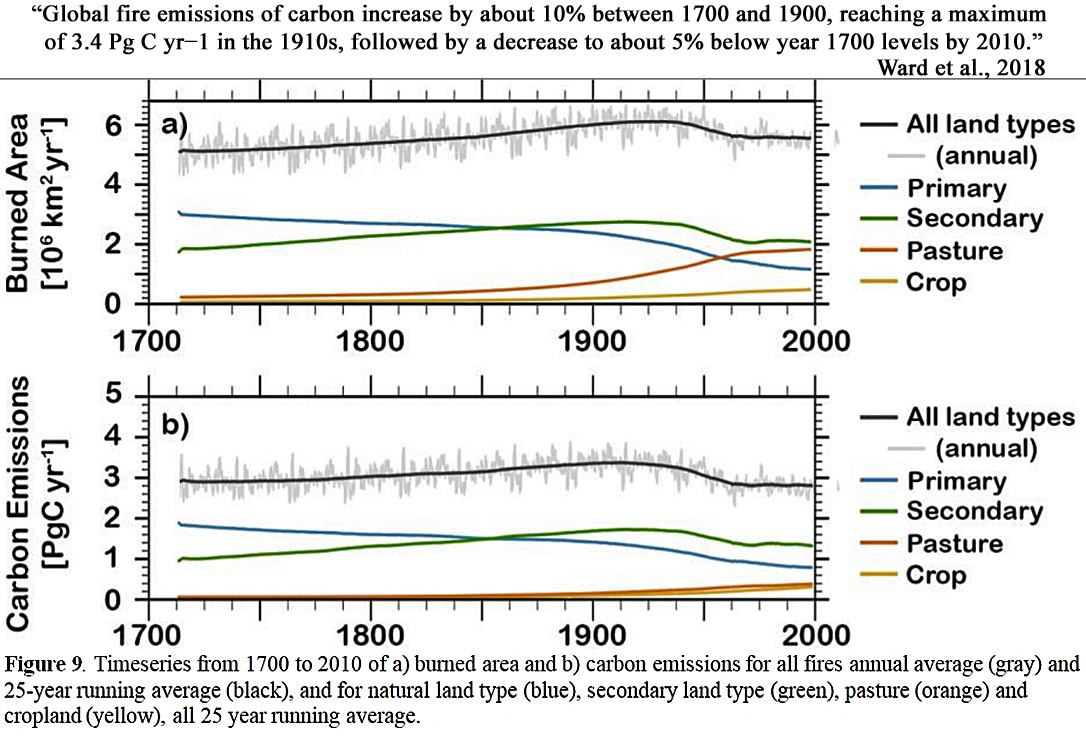

• “Globally, fires are a major source of carbon from the terrestrial biosphere to the atmosphere, occurring on a seasonal cycle and with substantial interannual variability. To understand past trends and variability in sources and sinks of terrestrial carbon, we need quantitative estimates of global fire distributions. … Global fire emissions of carbon increase by about 10% between 1700 and 1900, reaching a maximum of 3.4 Pg C yr−1 in the 1910s, followed by a decrease to about 5% below year 1700 levels by 2010.” (Ward et al., 2018)

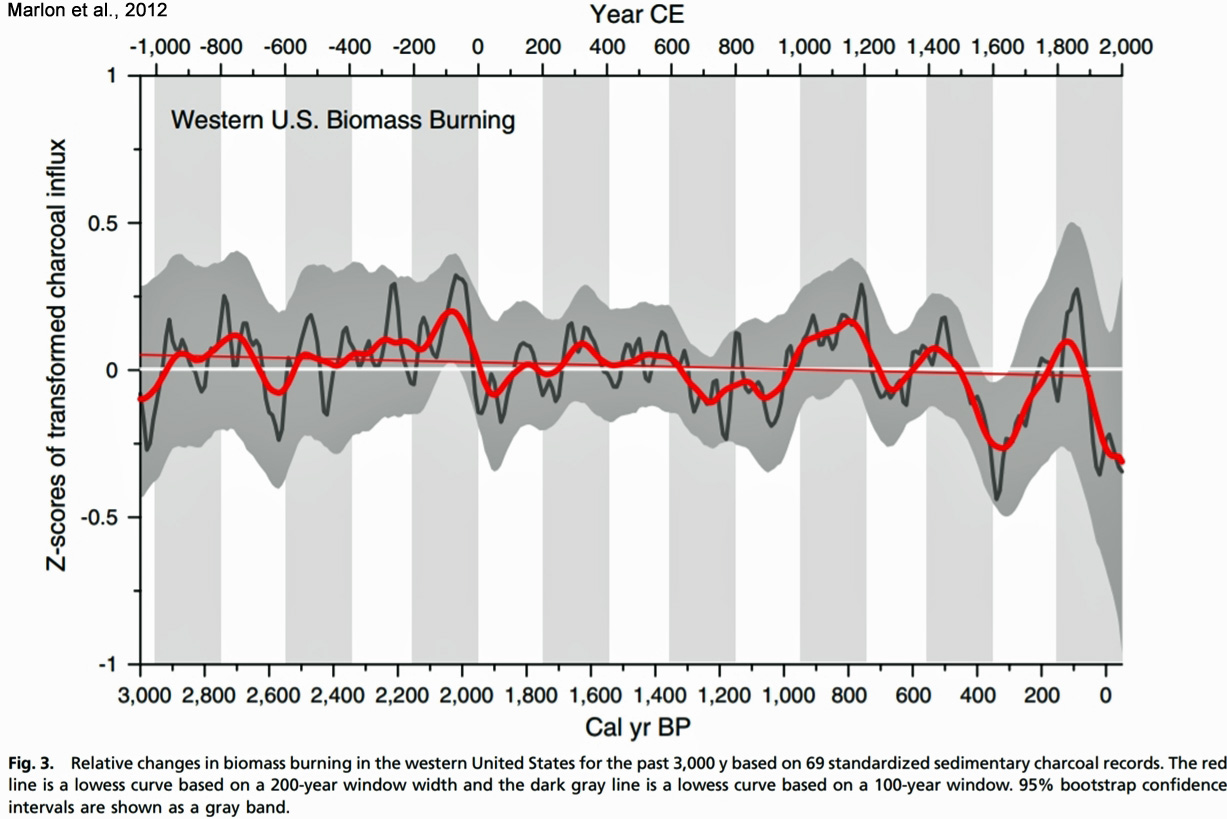

Image Source: (Ward et al., 2018)

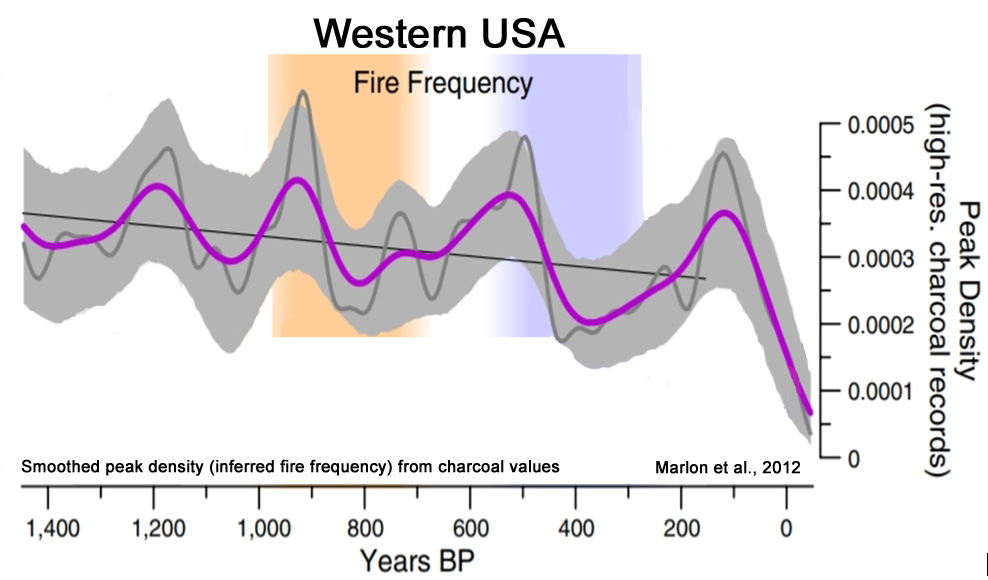

• “Understanding the causes and consequences of wildfires in forests of the western United States requires integrated information about fire, climate changes, and human activity on multiple temporal scales. We use sedimentary charcoal accumulation rates to construct long-term variations in fire during the past 3,000 y in the American West and compare this record to independent fire-history data from historical records and fire scars. There has been a slight decline in burning over the past 3,000 y, with the lowest levels attained during the 20th century and during the Little Ice Age (LIA, ca. 1400–1700 CE). Prominent peaks in forest fires occurred during the Medieval Climate Anomaly (ca. 950–1250 CE) and during the 1800s. … Analysis of climate reconstructions beginning from 500 CE and population data show that temperature and drought predict changes in biomass burning up to the late 1800s CE. Since the late 1800s , human activities and the ecological effects of recent high fire activity caused a large, abrupt decline in burning similar to the LIA fire decline. Consequently, there is now a forest “fire deficit” in the western United States attributable to the combined effects of human activities, ecological, and climate changes. Large fires in the late 20th and 21st century fires have begun to address the fire deficit, but it is continuing to grow.” (Marlon et al., 2012)

Images Source: Marlon et al., 2012

Real-world observational evidence – science – does not support Mann’s claims

Dr. Mann insists that the link between anthropogenic global warming and this past summer’s (NH) extreme weather events (droughts, floods, heat waves, and wildfires) is real and robust, even predicted by state-of-the-art climate modeling.

He finds the connection between AGW and extreme weather so compellingly self-evident that it’s easy for even the average reader to understand. Hence his tactical use of the “it’s not rocket science” maxim. Only “climate deniers” would disagree, he says.

Observational data from the real world do not affirm Mann’s claims, however. And science is, in its essence, rooted in real-world observational evidence, not theoretical pontification about presumed attribution.

It is therefore quite reasonable to conclude that the link between AGW and extreme weather events is indeed not rocket science.

It may not even be science.