The really significant content of a new paper being heavily-hyped by the media1 is what wasn’t said rather than what the authors discovered about metabolic rates and weight maintenance of a small sample of nine Southern Beaufort Sea bears in 2014 to 2016 (Pagano et al. 2018; Whiteman 2018).

This paper does not document starving or dying bears but merely found some (5/9) that lost weight when they should have been gaining, given that early April is the start of the ringed seal pupping season (Smith 1987) and the intensive spring feeding period for polar bears (Stirling et al. 1981).

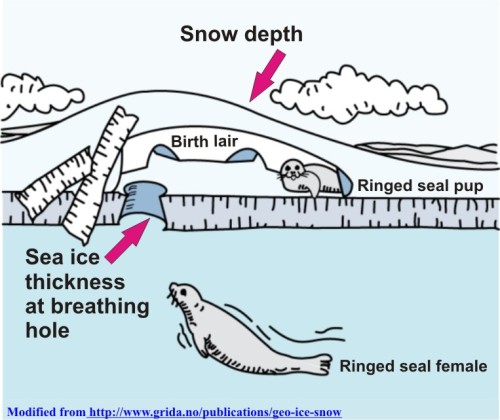

The question is, why were Southern Beaufort Sea polar bears off Prudhoe Bay (see map of the study area below), still hunting and capturing only adult and subadult ringed seals from sea ice leads when newborn ringed seal pups and their mothers should have been plentiful and relatively easily available in their birth lairs on the sea ice (see below)?

“Using video collar data, we documented bears’ hunting behavior and foraging success. Bears used sit-and-wait tactics to hunt seals 90% of the time, and stalking comprised the remaining 10% of hunts (movies S1 to S4) (19). Bears that successfully killed and ate adult or subadult ringed seals either gained or maintained body mass, whereas bears that only scavenged or showed no evidence of eating lost mass.”

There was no discussion in the paper of ringed seal birth lairs, or sea ice conditions at the time of the study, but several mentions about what might happen in the future to sea ice and potential consequences for polar bears. The press release did the same.

However, as you’ll see by the sea ice thickness maps below, there may be good reason for the lack of ringed seal lairs, and a general lack of seals except at the nearshore lead that forms because of tidal action: the ice just a bit further offshore ice looks too thick for a good crop of ringed seals in all three years of the study. This is reminiscent of conditions that occurred with devastating results in the mid-1970s and mid-2000s (Burns et al. 1975; Cherry et al. 2009; Harwood et al. 2012, 2015; Pilfold et al. 2012; Stirling 2002, Stirling et al. 1987). Those events affected primarily bears in the eastern half of the Southern Beaufort and were almost certainly responsible for the recorded decline in SB bear numbers in the 2001-2010 survey (Bromaghin et al. 2015; Crockford 2017; Crockford and Geist 2018).

It seems very odd to me that Pagano and colleagues suggested no reasons for the unexpectedly poor showing of polar bear hunting success during their study except a bit of hand-waving about higher-than-we-thought metabolic rates in the bears. For years, I’ve worried that the inevitable next episodes of thick Southern Beaufort spring ice would cause problems for polar bears and seals but we wouldn’t know it because whatever effects were documented would be blamed on reduced summer ice: I suspect that time may have come.

Figure 1 from Pagano et al. 2018 cropped to show only the study area off Alaska.

Here are some sea ice thickness maps from the US Navy for the three years of the study, with 2015 shown first.

Ice thickness map from the Naval Research Laboratory for 8 April 2015. Look at the thick band of 5 m thick ice along the exact stretch of Alaska coastline where the Pagano et al. 2018 study took place. Ringed seals cannot live, let alone give birth, in that kind of thick ice habitat and must move to areas of thinner ice with open leads (available to the east and west in 2015).

Below, ice thickness map for April 2016, showing slightly better conditions, especially to the east:

The band of thick multiyear ice (~5m thick) was less extensive in April 2016 but still present within the Pagano et al. 2018 study area. Thinner ice to the east and west would have been more attractive to pregnant ringed seals.

Below, ice thickness map for April 2014, showing ice thickness of 2 m or more across the region, which is probably too thick in most places for ringed seals:

Sea ice within the Pagano et al. 2018 study area in April 2014 was not quite as thick as 2015 and 2016 (only 3 – 4.5m thick) but this was probably enough to drive breeding ringed seals away. Note the lack of openings or areas of thinner ice that would attract seals except very close to shore.

From a 2015 post about Beaufort Sea polynyas, I discussed what marine mammal biologists Ian Stirling and colleagues had to say about polar bears and the effect of the Cape Bathurst polynya on the distribution of polar bears in spring (Stirling et al. 1981:49):

“Polar bears prey mainly upon ringed seals and, to a lesser degree, on bearded seals. Polar bears appear to be more abundant in polynya areas and along shoreleads, probably because the densities of seals are greater and they are more assessable. For example, between March and June in the Beaufort Sea from 1971 through 1975, 87% of the sightings of polar bears were made adjacent to floe edges or in unstable areas of 9/10 or 10/10 ice cover with intermittent patches of young ice.” [my bold]

Later, the same authors discussed why these areas of open water can be so important in the Southern Beaufort area (Stirling et al. 1981:54):

“One useful approach is to ask what would happen if the polynya was not there? Obviously this is impossible to evaluate on an experimental basis, but by examining the consequences or natural seasonal variation, some useful insights can be gained. For example, the influence of rapidly changing ice conditions on the availability of open water, and consequently on populations of seals and polar bears, has been observed in the western Arctic. Apparently in response to severe ice conditions in the Beaufort Sea during winter 1973-74, and to a lesser degree in winter 1974-75, numbers of ringed and bearded seals dropped by about 50% and productivity by about 90%. Concomitantly, numbers and productivity of polar bears declined markedly because of the reduction in the abundance of their prey species. …If the shoreleads of the western Arctic or Hudson Bay ceased opening during winter and spring, the effect on marine mammals would be devastating.”[my bold]

FOOTNOTES:

1. The media frenzy was no doubt aided by the fact that the authors made available four videos to the press that were part of their supplementary material.

Images, Video, and Other Media (see them here):

Movie S1

Video from a camera collar on a polar bear (bear #1) while on the sea ice of the Beaufort Sea in April 2014. This video shows an adult female polar bear on April 9, 2014 digging a hole in the sea ice potentially to entice a seal to come up to breath as she proceeds to still-hunt at this location and then pounces through the ice into the water. The video shows her on April 10, 2014 walking on the sea ice and on April 11, 2014 moving a recently caught ringed seal. The video shows her on April 12, 2014 interacting with an adult male polar bear.

Movie S2

Video from a camera collar on a polar bear (bear #4) while on the sea ice of the Beaufort Sea in April 2015. This video shows an adult female polar bear on April 16, 2014 swimming under the sea ice. The video shows her on April 18, 2014 still-hunting and pouncing through the ice into the water. On April 19, 2014, the video shows her still hunting and pouncing through the ice into the water at another location.

Movie S3

Video from a camera collar on a polar bear (bear #5) while on the sea ice of the Beaufort Sea in April 2015. This video shows an adult female polar bear on April 12, 2015 eating the muscle from the remains of an old seal carcass. Later on the same day, she is shown walking on the sea ice.

Movie S4

Video from a camera collar on a polar bear (bear #8) while on the sea ice of the Beaufort Sea in April 2016. This video shows an adult female polar bear on April 10, 2016 catching and eating a ringed seal. The video shows her on April 12, 2016 stalking, running at, and attempting to catch a bearded seal.

Some of todays headlines, in no particular order (note the hyperbole):

Polar Bears Really Are Starving Because of Global Warming, Study Shows (National Geographic, February 2018). https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2018/02/polar-bears-starve-melting-sea-ice-global-warming-study-beaufort-sea-environment/

Polar Bears Burn Calories Faster than Scientists Realized. That’s a Problem (InsideClimateNews, 1 February 2018) https://insideclimatenews.org/news/01022018/polar-bear-survival-video-arctic-sea-ice-loss-metabolism-study-climate-change

Polar bears ‘running out of food’ (BBC, 1 February 2018) http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-42909866

What Scientists Learned From Strapping a Camera to a Polar Bear(The Atlantic, February 2018) https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/02/what-scientists-learned-from-strapping-a-camera-to-a-polar-bear/552083/

High-tech bear-cams suggest polar bears having tougher time hunting (National Post, Canadian Press, 1 February 2018) http://nationalpost.com/pmn/news-pmn/canada-news-pmn/high-tech-cameras-suggest-polar-bears-having-tougher-time-hunting

Polar bears could become extinct faster than was feared, study says (The Guardian, 1 February 2018) https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/feb/01/polar-bears-climate-change

As Arctic sea ice thins, so do polar bears (Chicago Tribune, 1 February 2018) http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/science/ct-polar-bears-climate-change-20180201-story.html

The North’s ‘apex predator’ threatened by receding sea ice in the Beaufort Sea, study says (CBC, 1 February 2018) http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/polar-bear-beaufort-sea-study-1.4515155

“Pagano said it would be hard to say how widely these results might apply across the Beaufort Sea.

“How activity patterns and forging success rates might vary between regions and times of year is hard to speculate.”

Other researchers have shown declining polar bear populations across the Beaufort Sea region, but this study wasn’t meant to address questions of overall polar bear decline in the North.

“For this study we’re not looking at trends,” Pagano said.

“There’s no information here or documentation of how our results may relate to historical patterns simply because there isn’t any information, as far as we’re aware, of what the activity levels were of these bears historically.”

Metabolism study signals more trouble ahead for polar bears (Reuters, 1 February 2018) https://www.reuters.com/article/us-science-bears/metabolism-study-signals-more-trouble-ahead-for-polar-bears-idUSKBN1FL6AB

What Cameras on Polar Bears Show Us: It’s Tough Out There (New York Times, 1 February 2018) https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/01/climate/polar-bear-cameras.html

Polar bears are wasting away in a changing climate (NATURE, 1 February 2018) https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-01501-8

Polar bears’ bodies work 60% harder than thought — which makes surviving climate change even tougher (LA Times, 1 February 2018) http://www.latimes.com/science/sciencenow/la-sci-sn-polar-bears-metabolism-20180201-story.html

Polar bears are starving, and this video reveals why (Science Magazine, 1 February 2018) http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/02/polar-bears-are-starving-and-video-reveals-why

REFERENCES

Bromaghin, J.F., McDonald, T.L., Stirling, I., Derocher, A.E., Richardson, E.S., Rehehr, E.V., Douglas, D.C., Durner, G.M., Atwood, T. and Amstrup, S.C. 2015. Polar bear population dynamics in the southern Beaufort Sea during a period of sea ice decline. Ecological Applications 25(3):634-651. http://www.esajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1890/14-1129.1

Burns, J.J., Fay, F.H., and Shapiro, L.H. 1975. The relationships of marine mammal distributions, densities, and activities to sea ice conditions (Quarterly report for quarter ending September 30, 1975, projects #248 and 249). In Environmental Assessment of the Alaskan Continental Shelf, Principal Investigators’ Reports, July-September 1975, Volume 1. NOAA Environmental Research Laboratories, Boulder, Colorado. pp. 77-78. Pdf here.

Cherry, S.G., Derocher, A.E., Stirling, I., and Richardson, E.S. 2009.Fasting physiology of polar bears in relation to environmental change and breeding behavior in the Beaufort Sea. Polar Biology 32:383-391. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00300-008-0530-0#page-1

Crockford, S.J. and Geist, V. 2018. Conservation Fiasco. Range Magazine, Winter 2017/2018, pg. 26-27. Pdf here.

Crockford, S.J. 2017. Testing the hypothesis that routine sea ice coverage of 3-5 mkm2 results in a greater than 30% decline in population size of polar bears (Ursus maritimus). PeerJ Preprints 2 March 2017. Doi: 10.7287/peerj.preprints.2737v3 Open access. https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.2737v3

Harwood, L.A., Smith, T.G., George, J.C., Sandstrom, S.J., Walkusz, W. & Divoky, G.J. 2015. Change in the Beaufort Sea ecosystem: Diverging trends in body condition and/or production in five marine vertebrate species. Progress in Oceanography 136:263-273.

Harwood, L.A., Smith, T.G., Melling, H., Alikamik, J. and Kingsley, M.C.S. 2012. Ringed seals and sea ice in Canada’s western Arctic: harvest-based monitoring 1992-2011. Arctic 65:377-390. http://arctic.synergiesprairies.ca/arctic/index.php/arctic/article/view/4236

Pagano, A.M., Durner, G.M., Rode, K.D., Atwood, T.C., Atkinson, S.N., Peacock, E., Costa, D.P., Owen, M.A. and Williams, T.M. 2018.High-energy, high-fat lifestyle challenges an Arctic apex predator, the polar bear. Science 359 (6375): 568 DOI: 10.1126/science.aan8677

Pilfold, N.W., Derocher, A.E., Stirling, I., Richardson, E., and Andriashek, D. 2012. Age and sex composition of seals killed by polar bears in the eastern Beaufort Sea. PLoS ONE 7:e41429. Doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041429.

Smith, T.G. 1987. The ringed seal, Phoca hispida, of the Canadian Western Arctic. Canadian Bulletin of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 216. Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Ottawa. Google Books link http://tinyurl.com/ppqrf6k

Stirling, I. 2002. Polar bears and seals in the eastern Beaufort Sea and Amundsen Gulf: a synthesis of population trends and ecological relationships over three decades. Arctic 55 (Suppl. 1):59-76. http://arctic.synergiesprairies.ca/arctic/index.php/arctic/issue/view/42

Stirling, I, Cleator, H. and Smith, T.G. 1981. Marine mammals. In: Polynyas in the Canadian Arctic, Stirling, I. and Cleator, H. (eds), pg. 45-58. Canadian Wildlife Service, Occasional Paper No. 45. Ottawa. Pdf of pertinent excerpts of above papers here.

Stirling, I., Andriashek, D., and Calvert, W. 1993. Habitat preferences of polar bears in the western Canadian Arctic in late winter and spring. Polar Record 29:13-24. http://tinyurl.com/qxt33wj

Whiteman, J.P. 2018. Out of balance in the Arctic. Science 359 (6375):514-515.