Top climate economist Richard Tol injects some sanity into a hyper-ventilating climate debate

— Bjorn Lomborg (@BjornLomborg) August 21, 2023

In the most influential German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitunghttps://t.co/8HIoTShb4y

And here translated in English: https://t.co/OhEdBNco8Q pic.twitter.com/3RpPhLFYkp

By Richard Tol

Extinction Rebellion rebels against the possible extinction of humankind due to climate change. Some are more optimistic. David Attenborough fears that climate change will only end human civilization, reduce us all to hunter-gatherers. Others are more pessimistic. Bernie Sanders seems to think that climate change will do to the planet what the Death Star did to Alderaan. If any of this were true, or even remotely likely, I would join the rebellion. But it is not, fortunately, so I won’t.

To be clear, climate change is real, it is caused by humans, and it is a problem that needs to be solved. However, climate change is not an existential threat, at least not to humanity.

We’re all gonna fry

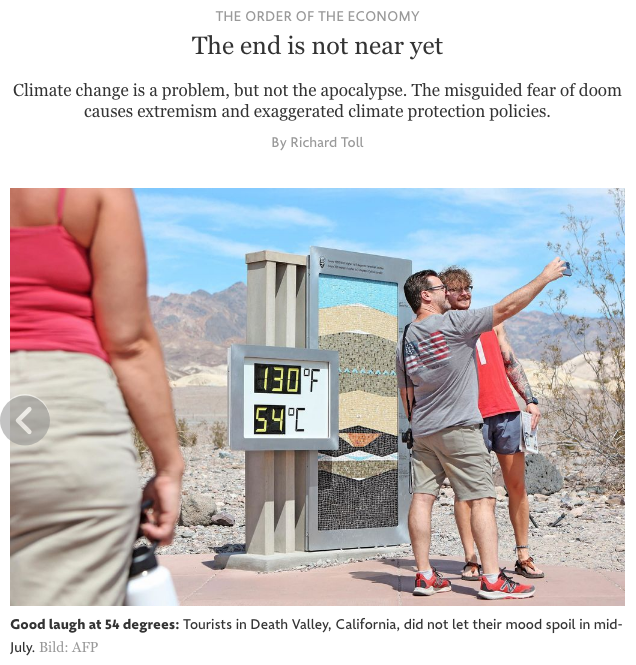

Death Valley is so called because the heat is so intense that it kills. The human body simply cannot cope. Like all warm-blooded animals, we must keep our core temperature stable lest our organs fail. Unlike other warm-blooded animals, we sweat to keep cool. The dry heat of Death Valley is not the worst. The human body can tolerate dry heat up to 55 degrees Celsius – but only 35 degrees with 100% humidity. Global warming means that more people will be exposed to intolerable heat for longer.

Jacobabad is one of the hottest cities on Earth. Journalists travelled there during a recent heatwave, apparently expecting to see the bodies piled high. Instead, they found that people do not just use their physiology to keep cool. They change their behaviour too, doing as little as possible and seeking out cooler areas. Indeed, the locals have seen heatwaves before and have created places that stay cool. People live in Death Valley too.

Jacobabad is poor. Where people have more money, air conditioning is the answer to heat. The number of air conditioners has gone up rapidly in China’s south, in Malaysia, and in India’s middle class. We see the same pattern in North America and Europe: Heat is dangerous to the poor, an inconvenience to the rich.

We’re all gonna drown

Many societies have a legend of a Great Flood. And now another one is coming: Massive sea level rise caused by climate change. You can download videos of what it will do to your favourite city, maps of what will happen to the place where you live. These reports often leave out the time scale. Sea levels are projected to rise by far less than a metre by 2100 – although more, much more is expected later, much later. A friend had worried our son about the coming deluge. I said that will not happen for a very long time. So, when I’m 14, he asked. In fact, it is something that his great-grandchildren may see.

These breathless stories overlook that we will not simply let this happen to us. Dikes were probably first built by the Sumerians some 5000 years ago. The Chinese independently invented the same technology a while later. Since then, technological progress in flood protection has been massive. It is much easier now to move large amounts of material – excavators and dump trucks instead of spades and wheelbarrows. Our understanding of coastal dynamics is rapidly improving with satellite imagery and computer models.

Bangladesh is the poster child of vulnerability to sea level rise. The Netherlands, another densely populated river delta in the path of big storms, is not. The Dutch actually make good money exporting their engineering know-how all over the world. While foreigners worry about Bangladesh, it has made remarkable progress in reducing the death toll from natural disasters: It fell by more than a factor 20 in the last 50 years even though the population more than doubled. We can expect more progress now that politics has stabilized and incomes are growing fast.

The Maldives too are seen to be at risk of the rising seas. Its government plays on this to create international sympathy. Its people are richer than those of Bulgaria and they have become very good at coastal engineering.

The real concerns about the impact of sea level rise are in countries that are poor, chaotic, or both. Coastal protection requires a government that is capable of raising money and delivering large and complex infrastructure projects – and cares about its people. It is no coincidence that the Netherlands started building proper dykes in 1850, shortly after it acquired a powerful central government that answered to the people. Poverty, incompetence, and corruption are more worrisome than rising seas. West Africa is at greater risk of sea level rise than South Asia. A look at the map of Abidjan shows that it is harder to protect than New Orleans – a glance at the international corruption tables shows just how much harder.

We’re all gonna starve

Climate change is predicted to reduce crop yield by up to half. Activists often skip those two little words, up to, and foretell widespread famine. Global average crop yields have increased three-fold over the last 60 years. If that trend continues and climate change takes away half, we will grow roughly the same amount of food, per head, in 2085 as we do today. Some experts argue that climate change has already reduced the rate of improvement of crop yields. Others counter that, since we produce more food than we need, the attention of farmers and crop researchers has shifted from growing more to better food. In Europe and North America, much cropland has been taken out of production and reverted back to nature.

The remarkable technological progress in agriculture has not reached everyone. The yield gap, the difference between a typical farm and a model farm in the same climate and on the same soil, can be as large as 90%. That is, if farmers would use current best practice, not some yet-to-be-invented future technology, they would get 10 times as much produce from their land. Let climate change take away half and they still grow 5 times as much.

The yield gap is largest in places where farmers lack access to modern seeds, fertilizers, pest control, and irrigation, often because land tenure is insecure, access to loans limited, and markets monopolized by middlemen or the state. The yield gap is smallest in countries where farmers are highly educated and well-capitalized. Again, poverty is a bigger problem than climate change.

Climate change or poverty?

These three examples have two things in common. First, on closer inspection, the predicted impacts of climate are not nearly as bad as some would like us to believe. Climate change is a problem, for sure, and the world would be better off without it. But it is not the apocalypse.

Second, the worst impacts of climate change are symptoms of underdevelopment and mismanagement. That implies that we should always ask what is the best way to improve the lot of future people. Is it greenhouse gas emission reduction or economic development?

Technology

The case of malaria is more subtle. The parasite grows faster when it is warmer. Mosquitoes that carry the parasite are more active when it is warmer, and need warm, still-standing water to breed. A warmer, wetter world will therefore see more malaria. However, there have been outbreaks of malaria as far north at Stockholm and even Murmansk. Malaria used to be endemic in the southern United States and in Italy. It is no longer. There are three reasons for this. We drained swamps and filled potholes, so that mosquitoes have fewer places to breed. The malaria medicine, that rich people can afford, prevents the worst symptoms and infection of other people. We sprayed DDT and then some more.

Malaria is now endemic only in hot countries, but this is because these countries are poor, not because these countries are hot. The story does not end here. The number of malaria deaths fell from some 900,000 per year in 2000 to about 550,000 in 2020, primarily because of the spread of bed nets treated with insecticide. President Bush the Younger led this initiative. It would have been his main legacy. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in a parallel universe where the Twin Towers still stand.

We can expect the malaria deaths will fall further, the warming climate notwithstanding. Financed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, there are now effective vaccines against malaria. Their roll-out has started. There is still hope that the last Guinea Worm dies before President Carter does. Let’s hope that malaria will be eradicated before Bill Gates passes away.

Twenty years ago, the spread of malaria was one of the main reasons for concern about climate change. Now, thanks to medical interventions and technological progress, we can look forward to a world without this awful disease.

This is not to say that every problem made worse by climate change can be ameliorated by a president or solved by a philanthropist. Some problems cannot be solved by technology, whether old, new, or yet-to-be-invented. A rotten government is at the core of many key vulnerabilities to climate change. But the case of malaria shows that greenhouse gas emission reduction is not the only way to reduce the impacts of climate change.

Apocalypse no

Climate change is a problem but it is not the end of world. People will die but humankind will not go extinct. People live and thrive near the poles and the equator, in the desert and in the rainforest. Homo Sapiens survived three ice ages and the Toba and Archiflegreo volcanic eruptions, armed with little more than fire, stone tools, and animal hides – sewing was invented later. We are the ultimate generalists, able to survive in extreme climates.

Merchants of doom

Why do so many believe that climate change will kill us all? Old stories are the best – or rather, good stories get old. People say that the music of the sixties was the best, but that is because we have forgotten all the rubbish that was released then and only recall the few songs that are truly brilliant. The same is true for stories. Stories about the end of the world are old. Every major culture has such stories. It is a good story, therefore, one that bears endless retelling and numerous variations.

The latest variant is that climate change will bring the world to an end. Casting a new message – climate change is bad – in an old and familiar narrative – the coming apocalypse – is an effective way to hook the audience. And this is exactly what environmentalists want. The environmental movement is massive. Its leaders need to bring in lots of people and donations because they derive their power and influence from that. The story of the apocalypse as a vehicle for climate change neatly ties in with painting emissions as sin and emission reduction as atonement. It is a brilliant marketing ploy.

“The end is nigh” is often followed by “but only I can save you”. Politicians want to build a legacy, something to remember them by for years or centuries to come. What better legacy than saving the world from certain destruction? We all like to be Will Smith, Angelina Jolie, or Bruce Willis. And so politicians exaggerate the seriousness of the climate problem they are trying to solve.

Journalists play along too. A headline screaming “unprecedented heat” sells more newspapers than “we’ve been here before”. A story about impending doom is better copy than a nuanced exposition about risk and opportunities. A scientist who warns of the horrors to come makes better TV than a professor who cautiously talks of ifs and buts.

It is small wonder then that the general public has a skewed understanding of the impacts of climate change. There are of course also people who think that the climate is not changing, that humans are not to blame, or that climate change will be a blessing. That is nonsense too. The world has warmed and will warm further. The main reason for this is the burning of fossil fuels. Climate change will do serious harm, particularly in developing countries and to biodiversity.

False prophesies

The prophesies of doom will be tested in a few years’ time. The 2015 Paris Agreement says the world should not warm by more than 2 degrees Celsius, and that it would be better to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Many activists have focused on the lower target. Exceed that and the world will burn. We will be roasted, toasted, fried and grilled.

The World Meteorological Organization forecasts that it is more likely than not that the global temperature will cross the 1.5 degrees Celsius threshold before 2028. The world will not end. Heatwaves, droughts, and storms will be a bit worse than they are already but life will go on.

There is a long history of failed prophesies. A group called the Seekers predicted that the world would end on 21 December 1954. It did not. Many of the Seekers then argued that the flood (and alien rescue) would come later. The lead prophet, Dorothy Martin, was a sought-after medium for another 38 years. Similarly, the Club of Rome predicted that civilization would collapse in 1980. One of its main authors, Paul Ehrlich, is still celebrated as a visionary.

Based on those and many similar observations, I expect that the doomsayers will say that world will end at 1.6 degrees Celsius warming, or 1.7 degrees. They will not lose their credibility, influence, or funding. The end is nigh, and it always will be nigh.

The risk of a backlash

Why does this matter? First, an increasing number of mostly young people suffer from climate anxiety. They truly believe what they write on their placards: I will die of old age, they will die of climate change. It does not just make them unhappy. If there is no future, why would you study? Why would you conform to the norms of a society that is about to collapse?

The misplaced belief in a climate apocalypse drives people to extremism. Most climate protests are peaceful. Some are mischievous but innocent. A few are violent or dangerous – such as blocking ambulances.

The main problem, however, with an exaggerated sense of climate doom is that targets for greenhouse gas emission reduction are too strict. Emissions should fall to zero, or perhaps below zero, in the long run. Governments across Europe want emissions to reach zero by 2050. That seems a long way away – 27 years – but it is not. Emissions of carbon dioxide are driven by the houses in which we live and how far away they are from our place of work or study, by the vehicles we use for travel and transport, by the machinery used in industry, and by the plants that generate electricity. Many of these things, particularly building and power plants, will still be around in 30 years’ time. We will have replaced our cars and heating systems by then – but carbon-neutral alternatives are not yet ready for prime-time. 2050 is nigh.

Popular support for climate policy is broad and shallow. Most people think that emissions should fall – but few people think they should pay more for their energy or be inconvenienced in any other way by climate policy. We have seen protests increase. France was first, of course, when les gilets jaunes took to the streets and blocked what was really a very modest carbon tax on transport fuels. In the Netherlands, the Boer en Burger Beweging, a single-issue anti-environment party, got the most votes in a recent election. In Germany, companies have long grumbled about the costs of the Energiewende. They have recently been joined by households worried that heat pumps will not get them through the winter. AfD is riding high in the polls If we could accept that the outlook for climate change is not so dire, then greenhouse gas emission reduction could move forward at a more acceptable pace – and so reduce the risk of a popular backlash against climate policy.

The first part of this post was published earlier. An edited and translated version was published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on 15 August 2023.

The author

Richard Tol is Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex and Professor of Climate Economics at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam. Among other things, he researches the costs and benefits of the UN climate targets, CO2 prices and the costs of adapting to climate change. Tol’s studies receive a great deal of international attention. He is the author of a textbook on the economics of climate change. In 2014, the environmental economist resigned as the author of a report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in protest against “scaremongering”.

Dr. Richard Tol: “Climate change is a problem, but not the apocalypse. The misguided fear of doom causes extremism and exaggerated climate protection policies.”

“The environmental movement is massive. Its leaders need to bring in lots of people and donations because they derive their power and influence from that. The story of the apocalypse as a vehicle for climate change neatly ties in with painting emissions as sin and emission reduction as atonement. It is a brilliant marketing ploy.”

“Global average crop yields have increased three-fold over the last 60 years. If that trend continues and climate change takes away half, we will grow roughly the same amount of food, per head, in 2085 as we do today…if farmers would use current best practice, not some yet-to-be-invented future technology, they would get 10 times as much produce from their land. Let climate change take away half and they still grow 5 times as much.”

The environmental movement is massive. Its leaders need to bring in lots of people and donations because they derive their power and influence from that. The story of the apocalypse as a vehicle for climate change neatly ties in with painting emissions as sin and emission reduction as atonement. It is a brilliant marketing ploy.

Journalists play along too. A headline screaming “unprecedented heat” sells more newspapers than “we’ve been here before”.