BY DR CARL HENEGHAN AND DR TOM JEFFERSON

Yesterday in Westminster Hall, MPs debated the Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response: International Agreement. Over 150,000 signed the petition to “not sign any WHO Pandemic Treaty unless it is approved via public referendum”. They don’t want the Government to commit to signing an international treaty unless it is approved through a public referendum.

Steve Brine MP said he was “puzzled by the debate”. We are too.

So, what is the Treaty about, and should we be concerned?

The WHO wants member states to negotiate a new international instrument to advance collective action for pandemic prevention, preparedness and response.

In March 2021, world leaders, including Boris Johnson, announced the need for a treaty to enhance international pandemic cooperation. In October, a WHO working group published a ‘zero draft’ report for consideration by the World Health Assembly (WHA), the WHO’s decision-making body. As a result, the WHA convened a second special session in December, where it established an Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB) to draft and negotiate the instrument with a view to its adoption under Article 19 of the WHO Constitution. Article 19 of the WHO’S Constitution gives the WHA the authority to adopt conventions or agreements on any matter within WHO’s competence.

Does the U.K. support the treaty? Well, Boris Johnson, as Prime Minister, was a signatory. In May 2022, the Government responded to the petition, stating it supported “a new legally-binding instrument.”

Government support that is pledged despite not knowing the substance of what is being proposed: the Government supports a new treaty “as part of a cooperative and comprehensive approach to pandemic prevention, preparedness and response”.

The zero draft for consideration was reported at the fourth INB meeting – known as the WHO CA+. The aim of the CA+ is “a world where pandemics are effectively controlled”. Have we learnt anything about respiratory agents?

One of the aims of the CA+ is confusing: it states it wants to “achieve universal health coverage”. But, the concept of universal health coverage is based on the 1948 WHO Constitution, which declares health a fundamental human right and commits to ensuring the highest attainable level of health for all – therefore, why should universal coverage be reserved for pandemics?

One of the primary reasons underpinning the treaty is the “recognition of the catastrophic failure of the international community to show solidarity and equity in response to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic”. There’s no need then for vital reflection on how we got it so wrong – it’s not just more of the same; this treaty sets out it will be much more.

Currently, the negotiating team is looking into the definition, means and procedure for declaring a pandemic, what this means in practice, how to finance pandemic preparedness and response initiatives and the setting up of a new Governing Body for overseeing the treaty.

It’s not all bad news: manufacturers are well catered for. Article 7(3a) states:

During inter-pandemic times all parties will coordinate, collaborate, facilitate and incentivise manufacturers of pandemic-related products to transfer relevant technology and know-how to capable manufacturer(s) (as defined below) on mutually agreed terms, including through technology transfer hubs and product development partnerships, and to address the needs to develop new pandemic-related products in a short time frame.

The petition asks for a referendum to decide whether the treaty will proceed. This isn’t going to happen – once the political will is in place, there’s little to stop the progress unless a block of countries at the WHA objects.

The issues that concern us are the definition, the costs and the actors.

We have previously noted the problems with defining a pandemic, and issues with the elusive definition of pandemic influenza have been pointed out as far back as 2011 when the need for any impact on morbidity and mortality was removed. Instead, all you needed was the worldwide spread of a new disease “against which the population has no immunity”.

There are also no widely accepted definitions for the end of the pandemic – who knows when this one will end?

As for the costs: Article 19(1c) of the draft report states:

Commit to prioritise and increase or maintain, including through greater collaboration between the health, finance and private sectors, as appropriate, domestic funding by allocating in its annual budgets not lower than 5% of its current health expenditure to pandemic prevention, preparedness, response and health systems recovery, notably for improving and sustaining relevant capacities and working to achieve universal health coverage. (emphasis added)

Has anyone considered the cost? Five per cent is roughly £7.5 billion for England and Wales – about half the General Practice budget gone. Any answers on what the XX% of GDP referred to below might add up to are much appreciated.

Commit to allocate, in accordance with its respective capacities, XX% of its gross domestic product for international cooperation and assistance on pandemic prevention, preparedness, response and health systems recovery, particularly for developing countries, including through international organisations and existing and new mechanisms.

As for the actors in all this, there will be many. Global politics is an excellent distractor for domestic problems; the WHO Global Pandemic Supply Chain and Logistics Network will ensure numerous opportunities for industry, and academia will gladly go along with an agenda that promises $XXX funding opportunities. At the centre will be the WHO – primarily a political organisation; it is essential that the past mistakes of the influenza narrative are not repeated.

In 2010, key scientists advising the WHO on pandemic planning had done paid work for industry that stood to gain from the guidance they authored. Deborah Cohen’s investigation showed that key experts contributing to the plan were conflicted. As a result, the definition of a pandemic was altered, billions of pounds of antivirals were stockpiled, and the WHO’s warning of two billion influenza H1N1 cases never materialised.

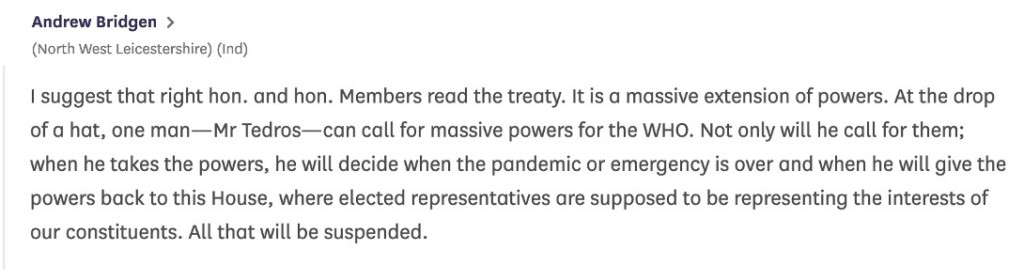

There’s been a lot (rightly) made about this treaty ceding power to an unelected body.

The treaty will be a legally binding instrument. There may be some downplaying of this when folk realise the implications. However, if a party wants to leave, it can do so at any time within two years from the date the WHO CA+ entered into force. But we will have to give one year’s notice (it’s unclear what happens after two years).

And as if you don’t need to be any more concerned, any party may propose amendments to the WHO CA+ that can be adopted by a two-thirds majority vote of the Parties present and voting at the session.

The INB will submit the treaty for consideration by the 77th World Health Assembly in May 2024. As Esther McVey said, we need “robust debate and an open review” of the plans.

Once the treaty is in force – to make it relevant and the political effort worthwhile – all you’ll need is another pandemic.

We do not need to spell out the catastrophic failures of the last three years. For now, just think that the same people are in charge and as our series on the UKHSA ‘evidence base’ for mask mandates shows, they do not care what any of us think.

This is not a U.K. problem, and we urge our non-U.K. readers to spread the word and, if they agree, our grave concerns.

We’ll be watching; we’ll keep you posted and keep writing. Somebody somewhere will take notice, perhaps.

Dr. Carl Heneghan is the Oxford Professor of Evidence Based Medicine and Dr. Tom Jefferson is an epidemiologist based in Rome who works with Professor Heneghan on the Cochrane Collaboration. This article was first published on their Substack blog, Trust The Evidence, which you can subscribe to here.