Wild boar. Kelp salad. Crickets in your pie crust.

These are just a few things that may end up on Thanksgiving menus as climate change takes its toll on the planet. https://t.co/O54Yhs87kD pic.twitter.com/BJ3CLzGMWA

— The Washington Post (@washingtonpost) November 25, 2021

https://twitter.com/dangainor/status/1463932831130951684

By Daisy Chung,Jessica Wolfrom, Aaron Steckelberg and Jake Crump

Drought, blistering heat waves and raging wildfires have gripped much of the West, stressing crops such as wheat — the basis of stuffing, rolls and pie crusts. In the Northeast, the fastest-warming region in the country, cranberries are budding earlier, making them more vulnerable to frost damage. And in the Southeast, intensifying hurricanes, driven by warming oceans, are forcing farmers to move turkeys northward to drier ground.

“Agriculture definitely stands to be impacted by climate change,” said Sonali McDermid, a climate scientist and associate professor of environmental studies at New York University. But, she added, agriculture “is not a passive recipient of climate change impacts. It is actually facilitating and driving climate change.”

Thanksgiving, one of the few nonreligious American holidays that most Americans celebrate, is centered around the notion of gathering for the autumnal harvest, said Amy Bentley, professor of food studies at New York University. But food production is the largest cause of global environmental change, according a report authored by a consortium of scientists. Agriculture is responsible for up to 30 percent of global greenhouse-gas emissions and 70 percent of freshwater use.

It’s a complicated dynamic: To mitigate the effects of global warming, we need to change agricultural practices. But food is already changing because of the warming climate.

“You can bet that under climate change scenarios, corn, cranberries, leafy greens like creamed spinach [and] turkey — all of these commodities are going to be constrained,” said Jessica Fanzo, professor of global food and agricultural policy and ethics at Johns Hopkins University and one of the authors of the report.

So what does this mean for the future of our Thanksgiving tables? Let’s start planning the feast.

…

Getting a turkey onto the table may become more challenging as climate change stands to affect prices and availability. “I don’t see, in the near term, a future where having it is not possible,” McDermid said. “I do see a future where it’s much more inequitable — and I see that happening very soon.”

But if traditional turkeys do disappear from our Thanksgiving tables, what we will eat instead?

Swapping birds for swine is one possibility.

…

Turkeys of the future could come from a lab instead of a farm.

Although some are skeptical that it will go mainstream in the near term, several start-ups developing lab-grown meat and seafood are betting the future of farm-to-table will be cell-to-harvest.

As consumers grow increasingly aware of the meat and dairy industry’s heavy carbon footprint — responsible for 14.5 percent of the planet’s greenhouse-gas emissions — cell-based alternatives are attracting a growing number of investors, such as Bill Gates and Richard Branson. Even meat industry heavyweights such as Tyson and Cargill are buying into cell-cultured technology, backing companies such as Upside Foods, Future Meat Technologies and Aleph Farms.

“There’s probably going to be a niche for things like lab-grown meat,” Tabler said. But he predicted that a majority of consumers will continue to gravitate toward conventionally grown turkey.

…

Consider crickets in your crust.

Although insects seldom make appearances on mainstream menus, eating bugs is integral to the history of America.

Indigenous peoples regularly incorporated insects into their diets, according to the FAO, but this practice dwindled when Western cultures suppressed insect-eating in the 18th and 19th centuries, dismissing it as primitive.

Now insects are showing up in flours, protein bars, chips and even pet feed. Studies show that crickets, grasshoppers and weevils are rich in protein and minerals including iron, zinc, copper and magnesium and that farming insects has environmental benefits including less land and water use and lower greenhouse-gas emissions.

Trade your bubbly for beer made with Kernza.

Kernza beer was first developed in 2016, and there are now three Kernza beers available in select states. Kernza in flour format can also be used in pie crusts and dinner rolls, and it makes a mean sourdough.

In the end, Thanksgiving is more about community than food. “I do think that [there is] growing acceptance that Thanksgiving is not about what exactly is on the table,” NYU’s McDermid said, “but about who is at the table.”

Jessica Wolfrom is a reporter and copy aide at The Washington Post. She also writes for the Real Estate section.

Aaron Steckelberg is a senior graphics reporter who creates maps, charts and diagrams that provide greater depth and context to stories over a wide range of topics. He has worked at the Post since 2016.

Jake Crump is a designer and web developer for The Washington Post since 2015.

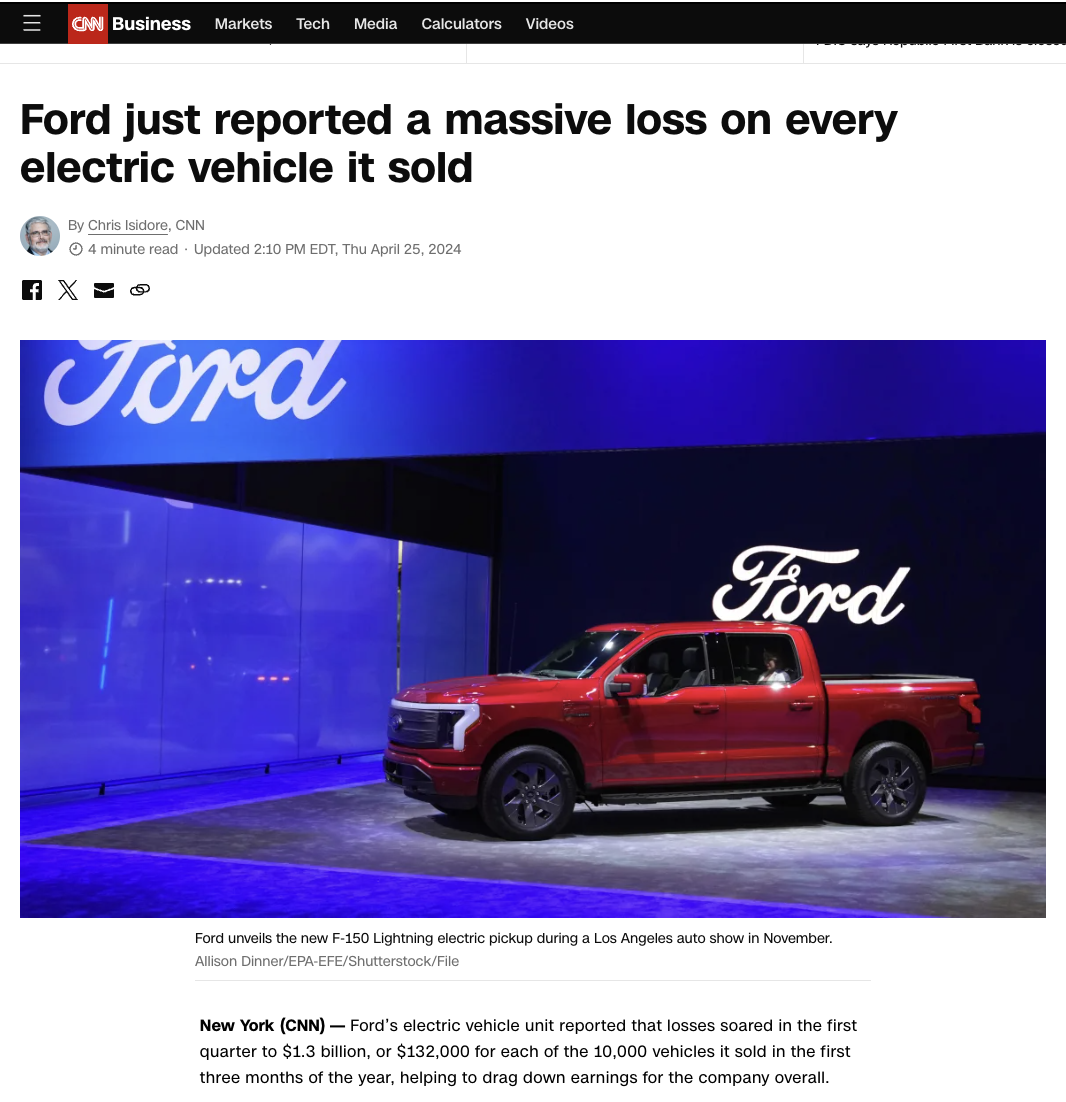

It is depressing how insistent WashPost is in describing climate as undermining everything

They tell us how heat is "stressing" wheat

— but conveniently forget to tell us that wheat production in 2021 once again broke all records https://t.co/3vNvOgztAP

— Bjorn Lomborg (@BjornLomborg) November 26, 2021

Global wheat production is larger than ever before

And this, while global wheat area has declined slightly since 1980shttps://t.co/YApmyQie8f pic.twitter.com/AEpME4Zj3d

— Bjorn Lomborg (@BjornLomborg) November 26, 2021

Indeed, global cereal production is setting records for 2021, but why report facts when you can scare people instead?https://t.co/zINfs1caxC pic.twitter.com/2aKitAUpFB

— Bjorn Lomborg (@BjornLomborg) November 26, 2021

In the future, agricultural production will increase 45%

Climate makes it increase slightly less

But climate policy, which WashPost pushes, will make production increase much less

WashPost never bothers to tell ushttps://t.co/E8BNaJLKbA pic.twitter.com/7ieVhkf0Kw

— Bjorn Lomborg (@BjornLomborg) November 26, 2021

In 2050, agricultural prices will be lower because of smarter production

Climate means prices will be slightly higher than otherwise

But climate policy, which WashPost pushes, will make prices much higher

WashPost never bothers to tell ushttps://t.co/E8BNaJLKbA pic.twitter.com/od7kiLFlxJ

— Bjorn Lomborg (@BjornLomborg) November 26, 2021