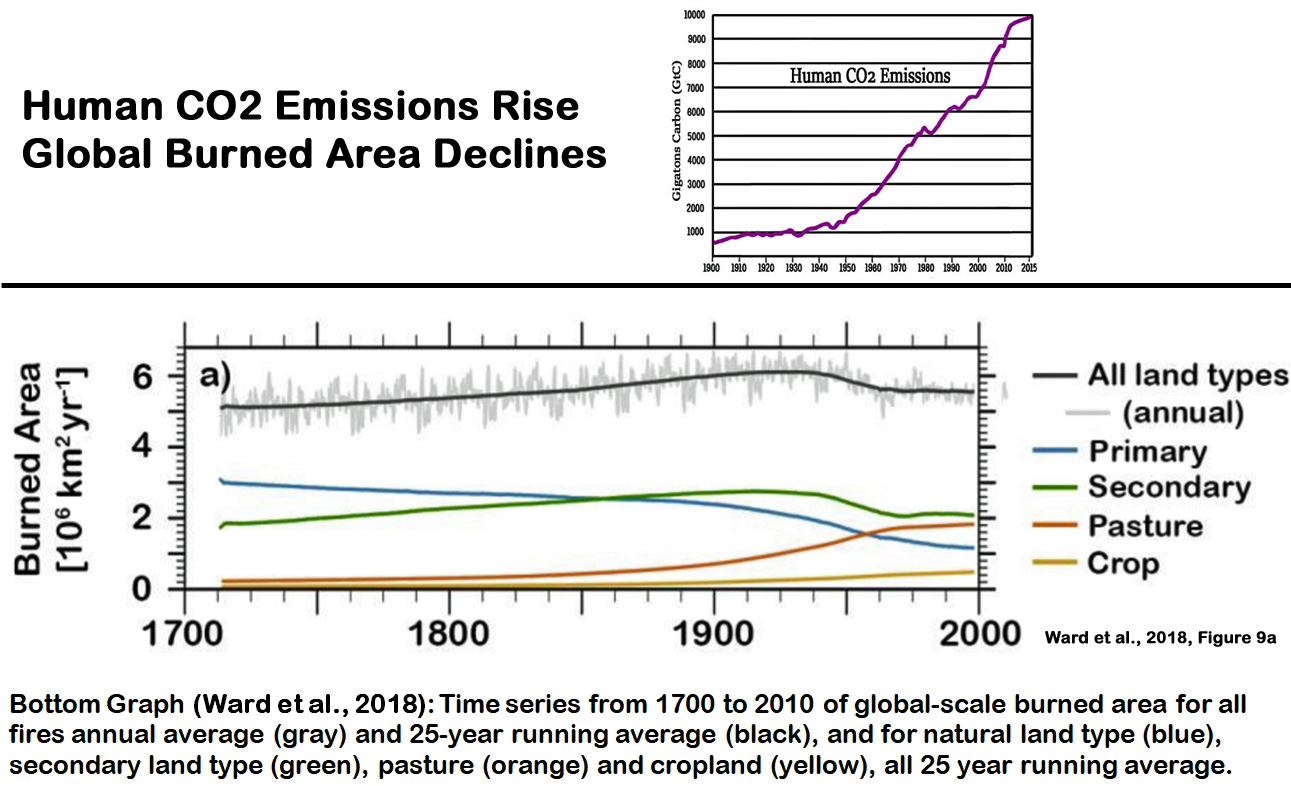

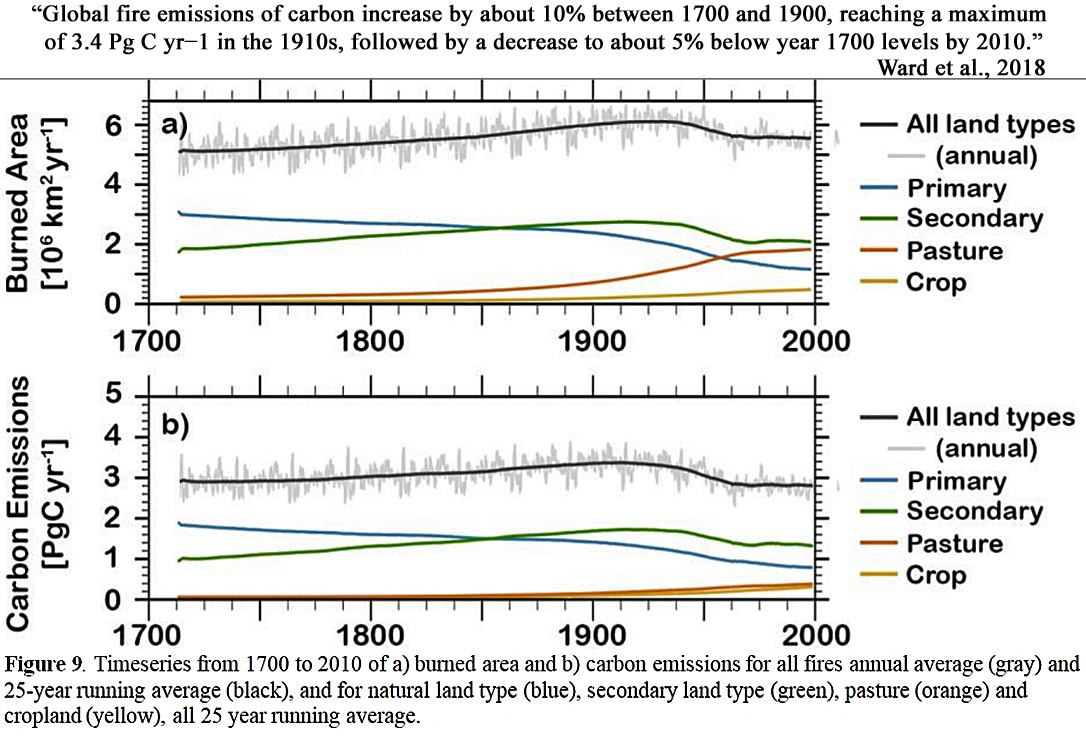

The purveyors of climate alarm posit that rising CO2 emissions cause up to 600% increases in burned area due to global warming. Newly published science thoroughly undermines these claims. Observational evidence affirms global-scale fire frequencies and burned area have actually been declining for decades (especially since the early 1900s), with overall biomass burning lower today than during the much colder Little Ice Age.

Bottom Graph Source: Ward et al., 2018

On a global scale, fire emissions/burned area peaked in the 1910s, but then plummeted to “about 5% below year 1700 levels by 2010” (Ward et al., 2018).

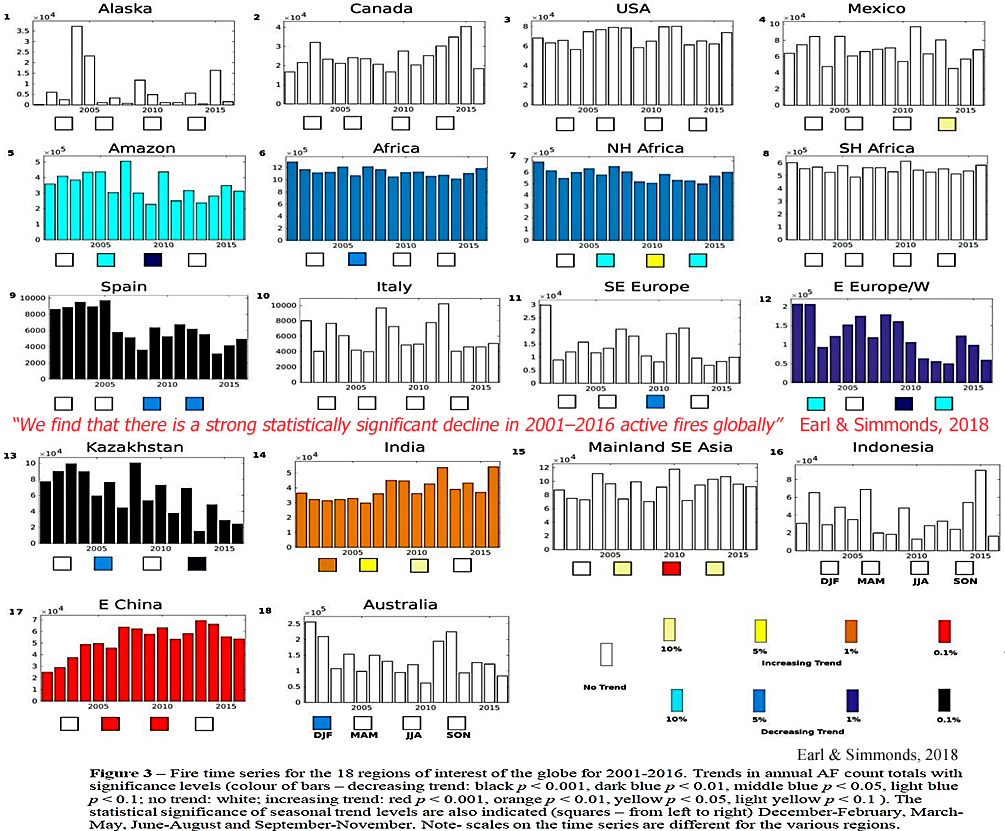

The decreasing trend in wildfires has continued unabated in the 21st century, as there has been “a strong statistically significant decline in 2001–2016 active fires globally” (Earl and Simmonds, 2018).

On a long-term scale, “global biomass burning during the past century has been lower than at any time in the past 2000 years” (Doerr and Santín, 2016).

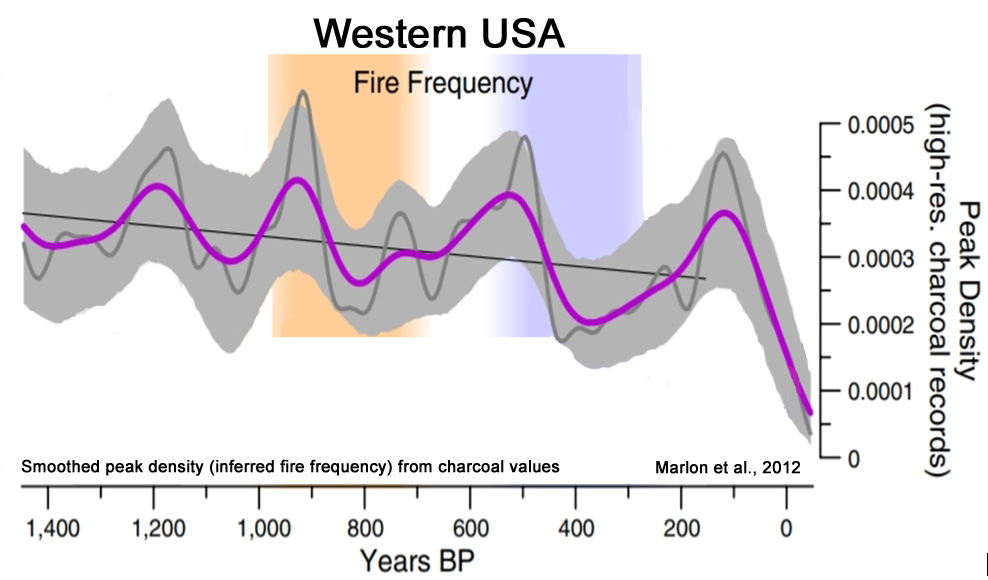

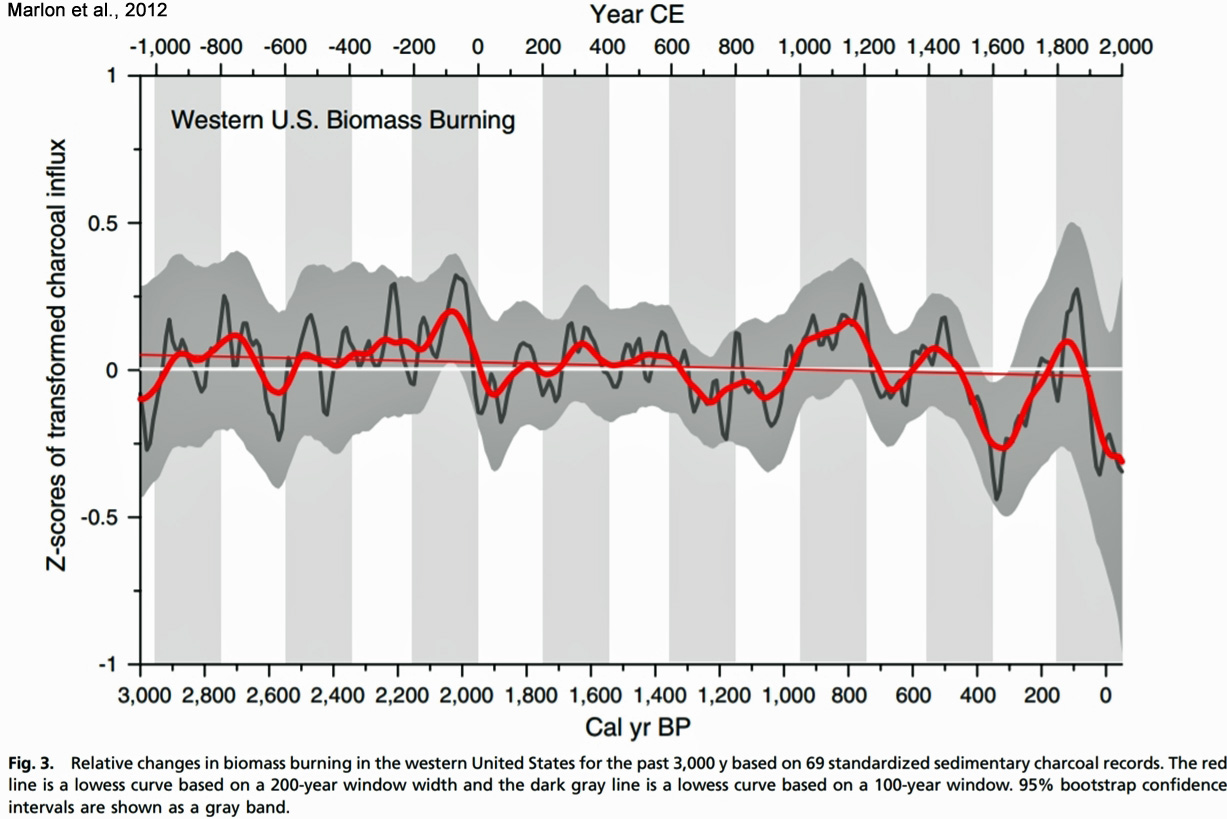

Even in the Western United States, where wildfires are currently ravaging the landscape, there has been a “decline in burning over the past 3,000 y[ears], with the lowest levels attained during the 20th century and during the Little Ice Age (LIA, ca. 1400–1700 CE)” (Marlon et al., 2012).

The perception of increasing fire occurrence vs. the observations of decreasing trends

Doerr and Santín (2016) characterize the association between global warming and increases in wildfires as a “perception” spawned by using selective regional data and short timescales (in other words, by excluding contradictory evidence). The alarming conclusions that wildfires are worsening due to rising anthropogenic CO2 emissions are then promulgated by mainstream media.

“Numerous reports, ranging from popular media through to peer-reviewed scientific literature, have led to a common perception

that fires have increased or worsened in recent years around the world. Where these reports are accompanied by quantitative observations, they are often based on short timescales and regional data for fire incidence or area burned, which do not necessarily reflect broader temporal or spatial realities.”

To summarize, there are “widely held perceptions both in the media and scientific papers of increasing fire occurrence, severity and resulting losses“, and yet “the quantitative evidence available does not support these perceived overall trends” (Doerr and Santín, 2016).

Ward et al., 2018

Trends and Variability of Global Fire Emissions

Due To Historical Anthropogenic Activities

“Globally, fires are a major source of carbon from the terrestrial biosphere to the atmosphere, occurring on a seasonal cycle and with substantial interannual variability. To understand past trends and variability in sources and sinks of terrestrial carbon, we need quantitative estimates of global fire distributions. … Global fire emissions of carbon increase by about 10% between 1700 and 1900, reaching a maximum of 3.4 Pg C yr−1 in the 1910s, followed by a decrease to about 5% below year 1700 levels by 2010. The decrease in emissions from the 1910s to the present day is driven mainly by land use change, with a smaller contribution from increased fire suppression due to increased human population and is largest in Sub‐Saharan Africa and South Asia. Interannual variability of global fire emissions is similar in the present day as in the early historical period, but present‐day wildfires would be more variable in the absence of land use change.”

Earl and Simmonds, 2018

Spatial and Temporal Variability and

Trends in 2001–2016 Global Fire Activity

“We find that there is a strong statistically significant decline in 2001–2016 active fires globally linked to an increase in net primary productivity observed in northern Africa, along with global agricultural expansion and intensification, which generally reduces fire activity.”

Doerr and Santín, 2016

Global trends in wildfire and its impacts:

perceptions versus realities in a changing world

“Wildfire has been an important process affecting the Earth’s surface and atmosphere for over 350 million years and human societies have coexisted with fire since their emergence. Yet many consider wildfire as an accelerating problem, with widely held perceptions both in the media and scientific papers of increasing fire occurrence, severity and resulting losses.”

“However, important exceptions aside, the quantitative evidence available does not support these perceived overall trends. Instead, global area burned appears to have overall declined over past decades, and there is increasing evidence that there is less fire in the global landscape today than centuries ago.”

“Analysis of charcoal records in sediments [Marlon et al., 2008] and isotope-ratio records in ice cores [Wang et al., 2010] suggest that global biomass burning during the past century has been lower than at any time in the past 2000 years.”

“Regarding fire severity, limited data are available. For the western USA, they indicate little change overall, and also that area burned at high severity has overall declined compared to pre-European settlement. Direct fatalities from fire and economic losses also show no clear trends over the past three decades. Trends in indirect impacts, such as health problems from smoke or disruption to social functioning, remain insufficiently quantified to be examined. Global predictions for increased fire under a warming climate highlight the already urgent need for a more sustainable coexistence with fire. The data evaluation presented here aims to contribute to this by reducing misconceptions and facilitating a more informed understanding of the realities of global fire.”

Marlon et al., 2012

Long-term perspective on

wildfires in the western USA

“Understanding the causes and consequences of wildfires in forests of the western United Statesrequires integrated information about fire, climate changes, and human activity on multiple temporal scales. We use sedimentary charcoal accumulation rates to construct long-term variations in fire during the past 3,000 y in the American West and compare this record to independent fire-history data from historical records and fire scars. There has been a slight decline in burning over the past 3,000 y, with the lowest levels attained during the 20th century and during the Little Ice Age (LIA, ca. 1400–1700 CE). Prominent peaks in forest fires occurred during the Medieval Climate Anomaly (ca. 950–1250 CE) and during the 1800s.”

“Analysis of climate reconstructions beginning from 500 CE and population data show that temperature and drought predict changes in biomass burning up to the late 1800s CE. Since the late 1800s , human activities and the ecological effects of recent high fire activity caused a large, abrupt decline in burning similar to the LIA fire decline. Consequently, there is now a forest “fire deficit” in the western United States attributable to the combined effects of human activities, ecological, and climate changes. Large fires in the late 20th and 21st century fires have begun to address the fire deficit, but it is continuing to grow.”