By Kenneth Richard on 29. December 2016

The ocean “acidification” narrative that claims humans are gradually lowering pH levels in sea water with their CO2 emissions may rest on presumptions, hypotheticals, and confirmation bias — not robust, observational scientific evidence.

A paper by Wei et al. (2015) published a year ago in the Journal of Geophysical Research effectively illustrates the vacuousness of the ocean “acidification” paradigm.

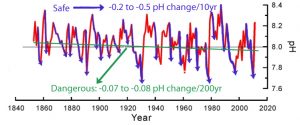

In the paper, the authors assert that “model calculations” (yes, calculations from modeling) have indicated oceanic pH levels may have decreased (i.e., lowered pH = less alkaline = more “acidic”) since the 1800s by a total of about 0.1 as consequence of the rise in anthropogenic CO2 emissions. This overall pH-lowering “trend” of less than 0.1 since the industrial era began is “predicted” to “potentially threaten the existence and development of many marine calcareous organisms”. Again, it’s the 150-year -0.1 trend in pH-lowering — which the authors admit is subject to “large errors” in measurement — that threatens the oceanic biosphere according to modeled predictions. In contrast, large natural pH drops of -0.2 to -0.5 occurring on 10-year timescales do not threaten “marine calcareous organisms.” Here are the key points from the paper:

Wei et al., 2015 Ocean acidification is predicted to reduce the saturation state of carbonate minerals in seawater and potentially threaten the existence and development of many marine calcareous organisms, such as calcareous microorganisms and corals. Model calculations have indicated an overall decrease in global seawater pH of 0.1 relative to the preIndustrial era value, and a further pH reduction of 0.2–0.3 over the next century.

We here estimate the OA rates from the two long (>150 years) annually resolved pH records from the northern SCS (this study) and the northern GBR [Great Barrier Reef], and the results indicate annual rates of -0.00039 +/- 0.00025 yr and -0.00034 +/- 0.00022 yr for the northern SCS [South China Sea] and the northern GBR [Great Barrier Reef], respectively. … [T]hese two time-series do not show significant decreasing trend for pH. Despite such large errors, estimated from these rates, the seawater pH has decreased by about 0.07–0.08 U over the past 200 years in these regions. … The average calculated seawater pH over the past 159 years was 8.04 [with a] a seawater pH variation range of 7.66–8.40.

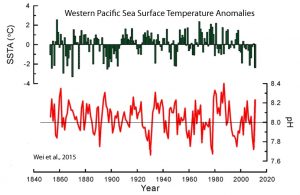

Below is the “money” graph from the paper that depicts sea surface temperature anomalies (top) and decadal-scale variations ranging between 7.66 and 8.40 in seawater pH (bottom) since the 1850s for the West Pacific Ocean:

First, notice that the Wei et al. (2015) sea surface temperature (SST) graph (top, green font) indicates there has been a rather significant cooling trend in the Western Pacific since the 1980s, and that SSTs are no warmer today than they were in the 1850s. This is consistent with other reconstructions that show modern SSTs in the region (NW Pacific) may still be a full degree C colder than they were during the Medieval Warm Period, and multiple degrees colder than they were a few thousand years ago (Yamamoto et al., 2016, Rosenthal et al., 2017).

But the bottom graph (red font) of pH variability since the mid-19th century is even more cogent. Notice that pH levels fluctuate between about 7.7 and 8.4 throughout the 150+ years, with many of the amplitudes found in the rises and falls in pH occurring at rates of + or – 0.2 to 0.5 per decade. So we are apparently expected to believe that changes in pH of + or – 0.2 to 0.5 per decade are not dangerous or “predicted” to “potentially threaten the existence and development of many marine calcareous organisms”, but the overall “acidic” or pH-lowering “trend” of less than -0.1 over 150 years is supposed to be dangerous to the oceanic biosphere. Below is an annotated version of this same graph brandishing this flagrant contradiction.

Daniel Cressey, who has previously helped expose a growing corruption problem infecting the scientific community, recently summarized the state of research on ocean “acidificaton” for the prestigious scientific journal Nature. He poignantly states that the lack of skepticism and an eager willingness to just accept the presumptions of others based upon their authoritative status (“groupthink”) may have “damage[d] the credibility of the ocean sciences”. And once scientific credibility is damaged, it becomes very difficult to earn that credibility back.

Cressey (2015) The state of the world’s seas is often painted as verging on catastrophe. But although some challenges are very real, others have been vastly overstated, researchers claim in a review paper. The team writes that scientists, journals and the media have fallen into a mode of groupthink that can damage the credibility of the ocean sciences. The controversial study exposes fault lines in the marine-science community. Carlos Duarte, a marine biologist at the University of Western Australia in Perth, and his colleagues say that gloomy media reports about ocean issues such as invasive species and coral die-offs are not always based on actual observations. It is not just journalists who are to blame, they maintain: the marine research community “may not have remained sufficiently sceptical” on the topic.

Scientists Find Higher CO2, Lowered pH Levels (‘Acidification’) Have Little To No Effect On Ocean-Dwelling Organisms

Scientists continue to construct experiments testing the effects of highly elevated CO2 (usually with volumes several times modern levels) on sea-living creatures. They routinely find that higher CO2 levels (and higher sea temperatures) have little to no effect on growth rates or survival for the species tested. In fact, it has been found in some cases that elevated CO2 benefits ocean-dwelling organisms, meaning that they thrive and prosper in these conditions. Obviously, these scientific studies wholly undermine the paradigm that envisions the long-term survival of the oceanic biosphere is jeopardized by rising anthropogenic CO2 emissions.

Uthicke et al., 2016 Near the vent site, the urchins experienced large daily variations in pH (> 1 unit) andpCO2 (> 2000 ppm) and average pH values (pHT 7.73) much below those expected under the most pessimistic future emission scenarios. Growth was measured over a 17-month period using tetracycline tagging of the calcareous feeding lanterns. Average-sized urchins grew more than twice as fast at the vent compared with those at an adjacent control site, and assumed larger sizes at the vent compared to the control site and two other sites at another reef near-by. … Thus, urchins did not only persist but actually ‘thrived’ under extreme CO2 conditions.

Vicente et al., 2016 The long-term exposure experiments revealed no effect on survival or growth rates of M. grandis to high pCO2 (1198 µatm), warmer temperatures (25.6°C), or combined high pCO2 with warmer temperature (1225 µatm, 25.7°C) treatments, indicating that M. grandis will continue to prosper under predicted increases in pCO2 and sea surface temperature.

Moore, 2016 If the forecasts of continued global warming are borne out, the oceans will also become warmer and will tend to outgas CO2, offsetting to some extent the small increased partial pressure that might otherwise occur. … An analysis of research on the effect of lower pH shows a net beneficial impact on the calcification, metabolism, growth, fertility, and survival of calcifying marine species when pH is lowered up to 0.3 units, which is beyond what is considered a plausible reduction during this century. … There is no evidence to support the claim that most calcifying marine species will become extinct owing to higher levels of CO2 in the atmosphere and lower pH in the oceans.

Hildebrandt et al., 2016 Elevated pCO2 did not directly affect grazing activities and body mass, suggesting that the copepods did not have additional energy demands for coping with acidification, neither during long-term exposure nor after immediate changes in pCO2. Shifts in seawater pH thus do not seem to challenge these copepod species.

Cross et al., 2016 A CO2 perturbation experiment was performed on the New Zealand terebratulide brachiopod Calloria inconspicua to investigate the effects of pH conditions predicted for 2050 and 2100 on the growth rate and ability to repair shell. Three treatments were used: an ambient pH control (pH 8.16), a mid-century scenario (pH 7.79), and an end-century scenario (pH 7.62). The ability to repair shell was not affected by acidified conditions with >80% of all damaged individuals at the start of the experiment completing shell repair after 12 weeks. Growth rates in undamaged individuals >3 mm in length were also not affected by lowered pH conditions

Heinrich et al., 2016 In this study, we tested the effects of elevated CO2 on the foraging and shelter-seeking behaviours of the reef-dwelling epaulette shark, Hemiscyllium ocellatum. Juvenile sharks were exposed for 30 d to control CO2 (400 µatm) and two elevated CO2 treatments (615 and 910 µatm), consistent with medium- and high-end projections for ocean pCO2 by 2100. Contrary to the effects observed in teleosts and in some other sharks, behaviour of the epaulette shark was unaffected by elevated CO2.

Sunjin and Jetfelt, 2016 [A]n increasing number of studies show tolerance of fish to increased levels of carbon dioxide. … We investigated the possible effects of CO2 on behavioural lateralization, swimming activity, and prey and predator olfactory preferences, all behaviours where disturbances have previously been reported in other fish species after exposure to elevated CO2. Interestingly, we failed to detect effects of carbon dioxide for most behaviours investigated

Schram et al., 2016 There were no significant temperature or pH effects on growth, net calcification, shell morphologies, or proximate body composition of snails. Our findings suggest that both gastropod species demonstrate resilience to initial exposure to temperature and pH changes predicted to occur over the next several hundred years globally and perhaps sooner along the WAP.

– See more at: http://notrickszone.com/2016/12/29/the-ocean-acidification-narrative-collapses-under-the-weight-of-new-scientific-evidence/#sthash.uz4F6G5P.dpuf