Five facts that challenge polar bear hybridization nonsense

Posted on May 23, 2016 | Comments Offon Five facts that challenge polar bear hybridization nonsense

It was inevitable, I suppose, that the putative hybrid shot in Arviat,Nunavut last week (see my post here) would initiate the global warming blame game.

Washington Post, 23 May 2016, Adam Popescu: “Love in the time of climate change: Grizzlies and polar bears are now mating”

Here are the five points you need to know about polar bear hybridization, as there are several nonsense statements contained in this Washington Post article.

1) POLAR BEAR TERRITORY IS NOT CONTRACTING

Steven Amstrup, head spokesperson for Polar Bears International (“Save Our Sea Ice!”)

“[Steven Amstrup], like other experts, characterizes this “new” bear relationship as more beneficial to grizzlies than polar bears. That’s because there are more grizzlies than polar bears and because grizzly territory is expanding while polar bear territory is contracting. What that adds up to is a good chance grizzlies could essentially dilute the polar bear population until it doesn’t exist at all, they say.”

“Polar bear territory is contracting” is a nonsense statement that is totally false. I dealt with a related claim here.

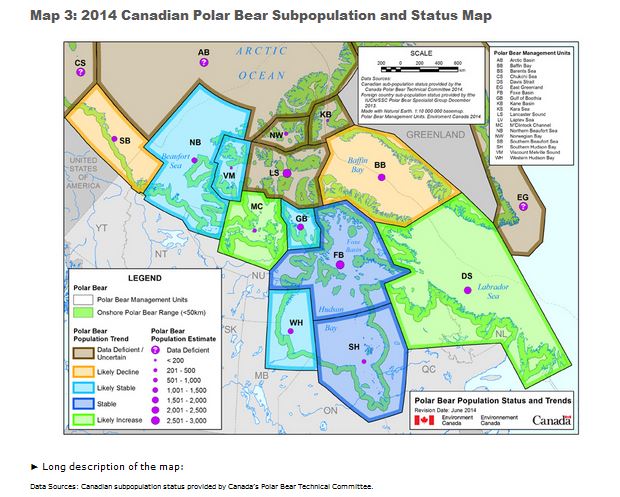

Territory might be prophesied to contract decades from now but so far,i t hasn’t changed a bit as a result of sea ice changes since 1950.The regions where hybridization has been documented (Doupé et al. 2007, see map in refs. below) are still polar bear territory, as is the region where the latest putative hybrid was shot (still not confirmed by DNA). All of the polar bear regions adjacent to grizzly populations in Canada have stable or increasing polar bear populations.

2) GRIZZLIES INVADING THE W. HUDSON BAY COAST ARE MOVING SOUTH

Derocher:

“It shouldn’t be a big surprise that grizzlies are moving north — everything is.”

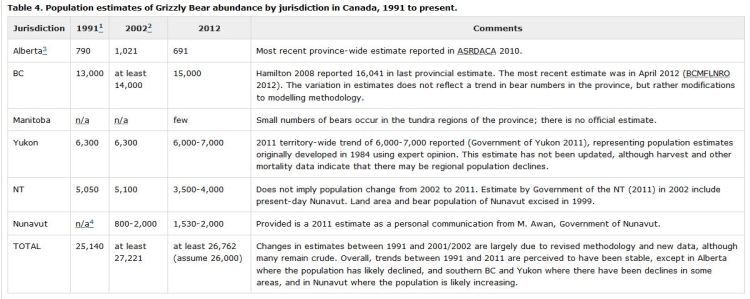

Map below shows where grizzly populations are found in Central and Northern Canada (according to the SARA Registry, 2012 – see table copied below). If a grizzly male met a polar bear female along western Hudson Bay (which is the most recent putative hybridization event took place and where more grizzlies have been seen in recent years), it could only have come from the north.

The population table below is from the SARA Registry about grizzlies in Canada, which shows “few” grizzlies in Manitoba (the province to the south of Nunavut. No grizzlies are listed for the provinces of Ontario or Quebec, which lie to the south-east.

How can grizzlies be moving north into Nunavut and Churchill, due to climate change or anything else? There are no grizzlies to the south (or so few they might as well be none).

3) HYBRIDS ARE STILL RARE

Derocher on back-crossed hybrids:

“What we’re starting to see in the Canadian Arctic is three-fourth grizzlies,” Derocher said, referring to the offspring of 50-50 hybrids that then mated with grizzlies.”

So far, exactly one of these back-crossed hybrids has been identified, in 2010! This female had a hybrid mother and a grizzly father (Crockford 2012b; Kelly et al. 2010) but hardly represents an epidemic of back-crossed hybrids. One first-generation hybrid has been confirmed in recent years (2006). That makes two confirmed hybrids in more than 30 years but no evidence this is an increase over previous occurrences. The Arviat animal has not yet been confirmed as a hybrid by DNA testing, as the WP article admits.

4) HYBRIDS LIVE LIKE POLAR BEARS, OUT ON THE SEA ICE

Derocher, on the behavior of hybrid back-crosses:

“How do they act? Probably more like grizzly bears, living on land.”

More speculative nonsense. All the mothers of natural hybrids have been polar bears, so they would have raised their cubs as polar bears – to live on the sea ice. A female hybrid cub would continue to live as a polar bear into adulthood, as she’d been trained (to hunt and seek mates on the sea ice), where she might have the occasion to meet an amorous male grizzly. Don’t forget that the reason the hybrid mating happens in the first place is that the grizzly males were behaving like polar bears (hunting on the sea ice in spring).

5) MALE GRIZZLIES MATE WITH FEMALE POLAR BEARS IN THE WILD

“Derocher said it will not be long before we start seeing female grizzlies bump into male polar bears, further straining the polar bear’s genetic variation.”

There’s a reason this kind of cross doesn’t work in the wild – grizzly females are more aggressive than male polar bears(Crockford 2012a,b). That’s why grizzlies dominate polar bears at whale carcasses.

The captive hybrids shown in the Washington Post article (from a German zoo) were the result of a mating that occurred after the female grizzly and male polar bear had lived together without mating for 24 years – it took that long for the behavioral barrier of the female grizzly’s dominance to break down (Crockford 2012a,b). That’s very, very unlikely in the wild unless populations are down to a few individuals – that might happen next century, but hardly “not long” from now.

References

Crockford, S.J. 2012a. Directionality in polar bear hybridization (1). Comment (May 1) to Hailer et al. 2012. “Nuclear genomic sequences reveal that polar bears are an old and distinct bear lineage.” Science336:344-347. http://www.sciencemag.org/content/336/6079/344.full and click on “leave a comment (1)” at the left. OR view directly athttp://comments.sciencemag.org/content/10.1126/science.1216424

This Report, “Nuclear genomic sequences reveal that polar bears are an old and distinct lineage” (Hailer et al., 20 April, p. 344) includes a discussion of hybridization between polar bears and brown bears that misses an important consideration. Hailer et al. say (p. 347) “introgressed brown bear material may have replaced the original polar bear mtDNA (Fig. 1D). This would imply that female brown bears mated with male polar bears and that the offspring backcrossed into the polar bear population [consistent with recent observations of fertile hybrids in the wild (25).”

However, the only example referred to by Kelly et al. was the 2nd generation offspring of a brown bear male and a hybrid female shot in 2010 in the western Canadian Arctic. Nuclear and mtDNA analysis of this animal indicated that its hybrid mother was the offspring of a male brown bear x female polar bear mating. The only other hybrid documented in the wild was the offspring of a brown bear male and a female polar bear, also shot in the western Canadian Arctic (Banks Island) in April 2006. Therefore, only male brown bear x female polar bear crosses have been documented in the wild, a point also missed by Edwards and colleagues last year (2011, Current Biology 21, 1251-1258).

The small number of verified hybridizations does not allow quantification of past introgression, but the examples from extant wild populations indicate only male brown bears are involved in inter-species matings. Two instances of hybridization involving polar bear males and brown bear females (the cross proposed by Hailer et al.) have been documented, but both involved captive animals. While hybridization with brown bears may indeed have occurred during the evolutionary history of the polar bear, the direction of introgression must be critically assessed with documented examples of inter-species matings.

Crockford, S.J. 2012b. Directionality in polar bear hybridization (2). Comment, with references (May 1) to Edwards et al. 2011. “Ancient hybridization and an Irish origin for the modern polar bear matriline.”Current Biology 21: 1251-1258. see here:

http://www.cell.com/current-biology/abstract/S0960-9822%2811%2900645-2#Comments

Hybridization between polar bears and brown bears has recently been discussed in two influential papers on the genetic evidence for polar bear evolution [1,2]: this one (Edwards et al.), which appeared last year in this journal, and another one published earlier this year in Science Magazine. Citing Kelly et al. [3] as evidence for the existence of confirmed brown bear/polar bear hybrids, the authors of these two genetic papers suggest that gene flow between polar bears and brown bears is just as likely in one direction as the other when hybridization occurs in the wild.

Both of these papers miss an important consideration. The only hybrid example mentioned by Kelly et al. [3] was the 2nd generation offspring of a brown bear male and a hybrid female shot in 2010 in the western Canadian Arctic. Analysis of nuclear and mtDNA indicated that this animal’s hybrid mother was the offspring of a male brown bear and a female polar bear. The only other hybrid documented in the wild was the offspring of a brown bear male and a female polar bear in 2006 (details on both hybrids were reported widely in newspapers around the world, with the details of the genetic testing provided in government-issued press releases and follow-up interviews. Recently, I confirmed the accuracy of these reports with the wildlife officials involved).

Therefore, only male brown bears x female polar bear crosses have been documented in the wild. The small number of verified hybridizations does not allow quantification of past introgression, but the examples from extant wild populations indicate only male brown bears are involved in inter-species matings.

Two instances of hybridization involving polar bear males and brown bear females (the cross proposed by Hailer et al. [1]) have been documented, but both involved captive animals. In the most recent case [4], mating occurred for the first time after the animals had been together for 24 years.

Brown bears mate from mid-May to July while polar bears mate April to May, leaving a brief period in late May when an early-breeding brown bear male and a late-breeding polar bear female might get together. Brown bear males also tend to emerge from their winter dens before females, increasing the chances that a brown bear male might encounter and accept a polar bear female as a mate.

In addition, although polar bears are often larger than brown bears, polar bears are less aggressive than brown bears during interactions between them [6, see pg. 16, 69]. This behavioral difference suggests another reason why only brown bears have been documented as the male partner in all inter-species mating with polar bears in the wild. It appears that for brown bears (as for wolves and domestic dogs, among many other examples), the less aggressive species is usually the the derived species and also the female partner in inter-species crosses [6-9].

Taken together, this evidence suggests that hybridization between brown bears and polar bears may be largely unidirectional in the wild and predictable based on life histories, behavior and evolutionary relationship. Although hybridization with brown bears may indeed have occurred during the evolutionary history of the polar bear, the direction of introgression must be critically assessed with documented examples of inter-species matings.

References

1. Hailer et al. 2012. Science 336, 344-347.

2. Edwards et al. 2011. Curr. Biol. 21, 1251-1258.

3. Kelly et al. 2010. Nature 468, 891.

4. Walker, M. 2009. Polar bear plus grizzly equals? BBC News Online, Friday 30 October.

5. Aars et al. 2006. Proceedings of the 14th IUCN Polar Bear Specialist Group, Seattle, Washington.

6. Bradley et al. 1991. J. Hered. 82, 192-196.

7. Crockford, S.J. 2006. Rhythms of Life: Thyroid Hormone and the Origin of Species (Victoria: Trafford).

8. Kaneshiro, K. Y. 1980. Evolution 34, 437-444.

9. Roca et al. 2005. Nat. Genet. 37, 96-100

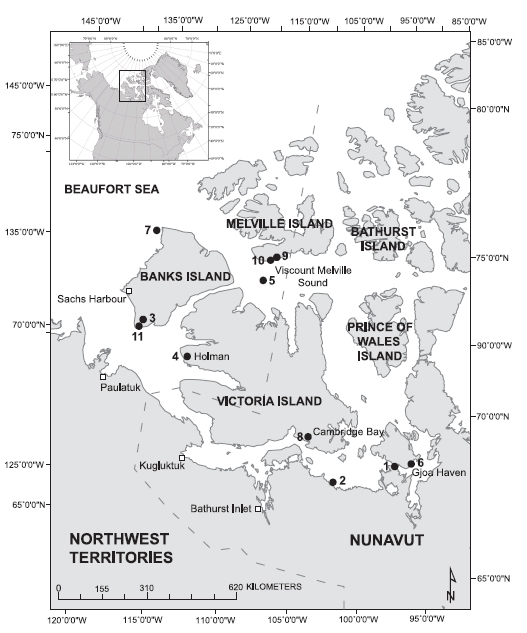

Doupé, J.P., England, J.H., Furze, M. and Paetkau, D. 2007. Most northerly observation of a grizzly bear (Ursus arctos) in Canada: photographic and DNA evidence from Melville Island, Northwest Territories. Arctic 60:271-276.http://arctic.synergiesprairies.ca/arctic/index.php/arctic/article/view/219

Figure 1 from above, showing the locations of “selected examples of grizzly bear sightings in the southern Canadian Arctic Archipelago,” up to and including the hybrid shot in 2006. See map with caption (with dates) here.

END